On March 23, 1982, a group of 150 aggravated men and women arrived on nothing but a wing and a prayer at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization base in Keflavík to protest against what they believed to be NATO’s total disrespect for something very dear to them. Elves, who, according to them, were in grave danger.

They were few, but they were loud, and saddened to see American phantom jets and AWACS reconnaissance planes (airborne early warning and control) allegedly desecrating a holy ground and disturbing the life of the Icelandic hidden people, or huldufólk. These 150 people changed nothing really at the time, although they were let inside the premises to do their inspection, and reported to the New York Times a week later on their efforts.

It might sound silly, but traditional folklore and huldufólk affairs are matters of great concern for many Icelanders, and these elf-like little people enjoy some serious political representation by advocates who believe in their existence and wish to preserve their “old natural ways.”

According to one study conducted by the University of Iceland’s Faculty of Social Sciences in 2007, only 8 percent firmly confirmed their belief in the existence of supernatural entities; however, a staggering 54 percent didn’t want to deny it. One-fifth of respondents embraced the idea that humans might not be the sole inhabitants of Icelandic landscapes and others could potentially live among them invisibly.

The study was carried out with 1,000 participants of different demographics in 2006 and 2007 upon request of Terry Gunnell, associate folklore professor at the University of Iceland, who was surprised, not by the results per se, but by the extent of how much Icelanders differ from other nations in terms of how reluctant they were to deny traditional superstitious beliefs. In Iceland, people are “more open to phenomena like dreaming the future, forebodings, ghosts and elves than other nations,” he declared for the Iceland Review.

Additionally, according to Fréttabladid, Iceland’s most renowned newspaper, these results from 2007 were more or less similar, if not identical, to the ones presented by Professor Erlendur Haraldsson and his study from four decades ago in 1974, which only proves that not much has changed over the years.

“You can’t live in this landscape and not believe in a force greater than you,” explains Professor Adalheidur Gudmundsdottir, who teaches Folklore and Medieval Icelandic literature at the Faculty of Icelandic and Comparative Cultural Studies Department at the university. In that same interview she gave to Emma Jane Kirby for her BBC story, “Why Icelanders are Wary of Elves Living Beneath the Rocks,” the professor politely asks viewers not to be too quick to judge and think of “Icelanders as uneducated peasants who believe in fairies,” but to take a closer look where they live and try to understand “why the power of folklore here is so strong.”

So what are they, these ancient elvish creatures that live among men but nobody sees? Well, according to folklore legends dating from as far back as the Viking age, around 1,000 years ago, human-like invisible elves shared the same lands in Iceland as people do. They are usually smaller than us, three feet high, although they can be of the same height. They live just like us. They build houses, they raise families, they farm, fish, pick berries, go to church, etc. They are friendly little creatures who respect nature and everything around them, and want to be respected in return.

However, many times this is not the case. For example, it is said that if their natural habitat is disturbed, bad things happen.

Not to get the wrong impression, in Iceland, not everyone believes or is afraid of upsetting the elves. On the contrary, they are a progressive nation where, for instance, the government had voted for equal pay for men and women, and as of January 1, 2018, it is now illegal for employers to differentiate between them in terms of salary for the same position. However, progressiveness also means openness to accepting different opinions and taking unconventional beliefs into account. Which helps explain why this was not the first, nor the sole incident, where the huldufólk had their say or influenced some major decisions in the country’s development and its policy.

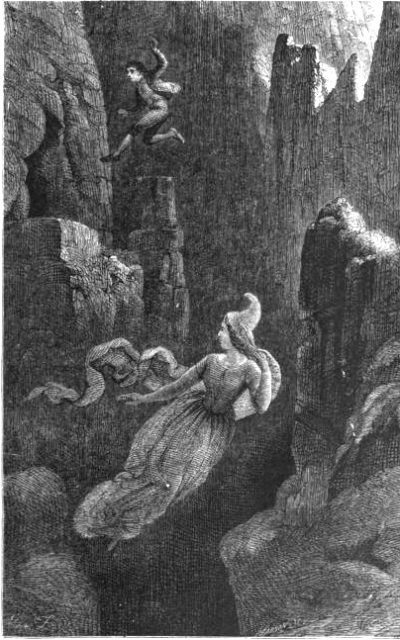

In the 1930s, when Iceland’s government wished to connect Reykjavik with Kópavogur, then relatively small, now one of the highest populated towns on the island, a rock named Álfhóll, meaning “Elfhill,” caused a stir. It’s just south of the capital, and a direct road straight through the giant rock was the shortest and the most efficient way to go. It was supposed to make everything easier for the neighboring cities, so plans ware drawn up and everything began well.

However, it turned out the huldufólk who dwelt in the rock were apparently not on the same page with the government about its being demolished, and caused problems for decades of construction workers. Machines broke down mysteriously, workers got sick, the weather changed from bad to worse, and the funds dried up. The project was abandoned. Within a decade, they made a second attempt. But it was the same story once again. A third attempt was made almost 40 years later, and what do you know–they made a curve and left Álfhóll untouched.

In another instance, the Icelandic Road and Coastal Commission had to get a permission from the Supreme Court to build a road from the Alftanes peninsula to Garðabær in Reykjavik, after a group of environmentalist and elf advocates, calling themselves Friends of the Lava, filed an official complaint explaining the road would pass straight through a huldufólk habitat, and a huge rock standing on the road was actually a legendary elf church named Ofeigskirkja.

The rock, 70 tons in weight, had to be moved with care by the bulldozers–one and a half years later, after the elves were given enough time to choose another location and move on. Ragnhildur Jónsdóttir from Álfagarðurinn (the elf garden) in Hafnarfjörður, who specializes in dealing with problems of an elvish nature, oversaw everything on site. Jónsdóttir, also known as The Elf Whisperer of Iceland, reported to the BBC that “a pact between elves and men was reached,” and the huldufólk were enjoying their new surroundings.

This same elf whisperer was called into action a few years back when Árni Johnsen, a former member of the Icelandic parliament, lost control of his SUV and was supposedly saved by a 30-ton boulder, or specifically by the elves that apparently lived in it. His vehicle was completely trashed, but he managed to escape uninjured, and the boulder was carefully moved via ferry near his home, on grass so they can have sheep, and with the window side of it facing the ocean, just as they asked, and as the whisperer whispered to him.

Anyhow, back to the subject at hand. Though Iceland was one of the founding members of the North Atlantic Organization, referred to as NATO’s “eye in the north,” the majority of the Icelandic people were, let’s say not so happy about their government’s decision to “take a side” and get involved in the Cold War. Iceland was for a long time a peaceful, neutral country, and has been ever since, and its people, known to be friendly and nonviolent, were against any form of militarization. Naturally, protests have taken place since the treaty was first formed in 1949, and it is not really a surprise that the huldufólk found representatives to speak for them in this instance as well.

The bottom line is, these few incidents maybe do and maybe don’t explain anything in terms of the Icelandic elvish belief. Maybe they are only isolated tales blown up out of proportion and nothing else. They do, however, aim to demonstrate a respect the Icelandic government is willing to show to those who chose to believe in them, even if they are only a few. And of course to the elves themselves, if they happen to exist.

After all, does it really matter? Taking their probable existence into account shows how much a nation is devoted to preserving traditional values, and most of all respecting other people’s values and opinions.

Well, except for that one time back in 1949, and one very touchy subject. When the government that has no Ministry of Defense, no army, nor intentional for quarrels with anyone, decided to lend their airport in Keflavík for military purposes despite loud and continual objection by a large fraction of the population, including the elves probably, who knows. They are still to make their official stance.