The elephant birds, which were giant ratites native to Madagascar, have been extinct since at least the 17th century.

Étienne de Flacourt, a French governor of Madagascar in the 1640s and 1650s, mentions an ostrich-like bird said to inhabit unpopulated regions. In 1659, Flacourt wrote: “vouropatra – a large bird which haunts the Ampatres and lays eggs like the ostriches.

So that the people of these places may not take it, it seeks the most lonely places.” Marco Polo also mentioned hearing stories of enormous birds during his journey to the East during the late 13th century. These accounts are today believed to describe elephant birds.

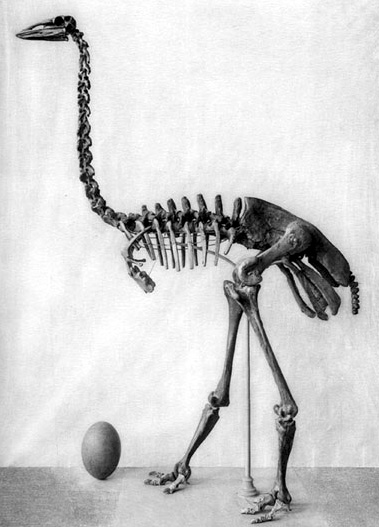

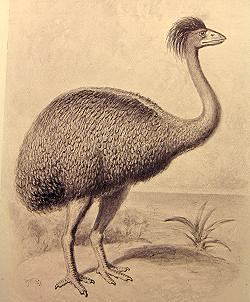

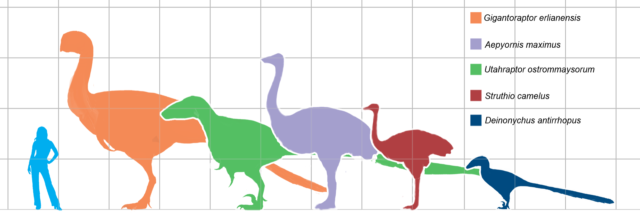

Aepyornis, believed to have been more than 3 m (9.8 ft) tall and weighing perhaps in the range of 350 to 500 kg (770 to 1,100 lb), was at the time the world’s largest bird. Only the much older species Dromornis stirtoni from Australia is known to rival it in size among the fossil record and is reported to have shared the same estimated upper weight, 500 kg (1,100 lb).

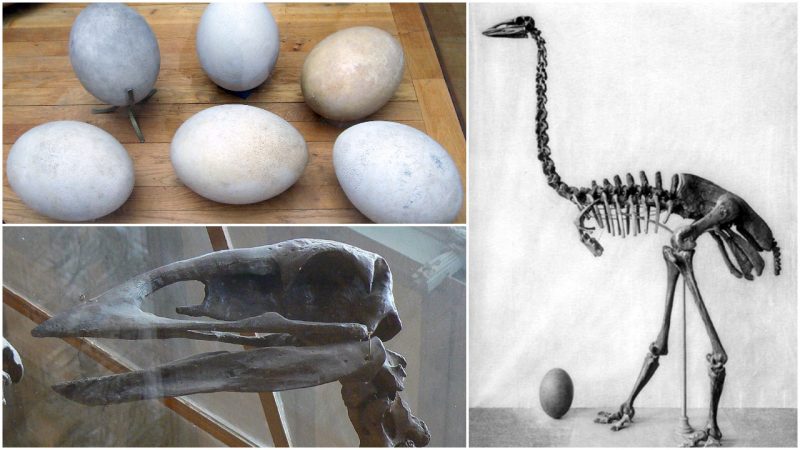

Remains of Aepyornis adults and eggs have been found; in some cases, the eggs have a circumference of more than 1 m (3.3 ft) and a length up to 34 cm (13 in), the largest type of bird egg ever found. The egg weighed about 10 kg (22 lb). The egg volume is about 160 times greater than that of a chicken egg

Like the ostrich, rhea, cassowary, emu, kiwi and extinct moa, Mullerornis and Aepyornis were ratites; they could not fly, and their breast bones had no keel. Because Madagascar and Africa separated before the ratite lineage arose, Aepyornis has been thought to have dispersed and become flightless and gigantic in situ.

More recently, it has been deduced from DNA sequence comparisons that the closest living relatives of elephant birds are New Zealand Kiwis. Elephant birds are actually part of the mid-Cenozoic Australian ratite radiation.

Their ancestors flew across the Indian Ocean well after Gondwana broke apart. The existence of possible flying paleognaths in the Miocene such as Proapteryx further supports the view that ratites did not diversify in response to vicariance. Gondwana broke apart in the Cretaceous, and their phylogenetic tree does not match the process of continental drift.

It is widely believed that the extinction of Aepyornis was a result of human activity. The birds were initially widespread, occurring from the northern to the southern tip of Madagascar. One theory states that humans hunted the elephant birds to extinction in a very short time for such a large landmass (the Blitzkrieg hypothesis).

There is indeed evidence that they were preyed on and their preferred habitats destroyed. Their eggs may have been particularly vulnerable. A recent archaeological study found remains of eggshells among the remains of human fires, suggesting that the eggs regularly provided meals for entire families.

The exact period they died out in is also not certain; tales of these giant birds may have persisted for centuries in folk memory. There is archaeological evidence of Aepyornis from a radiocarbon-dated bone at 1880 ± 70 BP (approximately 120 CE) with signs of butchering and by the radiocarbon dating of shells, about 1000 BP (approximately 1000 CE).