The story of the keyboard layout that we use every day is older than you might think; some would argue that the origin of the keyboard layout is older than the keyboard itself, or some variants of the keyboard such as the typewriter.

However, for argument sake let’s just start our story in 1875, when Christopher Sholes teamed up with Amos Densmore and applied some innovations on already in practice keyboard so that the letter in the sequence weren’t located too close and the punching bars/type bars that would come from the opposite sides.

The famous keyboard layout that you encounter on numerous occasion every day, is known as the QWERTY layout, made by simply joining the first five key letter on the top left corner of the keyboard.

The layout, though it might seem odd, doesn’t have any singular thought or theory behind it, rather a whole set of events that passed a number of trial and error tests, by the early developers of the systems.

The developers were after a system that was not just productive but would also exert minimal strain on the hands of the typist. After the initial introduction of the QWERTY, the system simply stuck around and the subsequent minds thought to keep the layout as it had gotten embedded too deep in our system due to inertia.

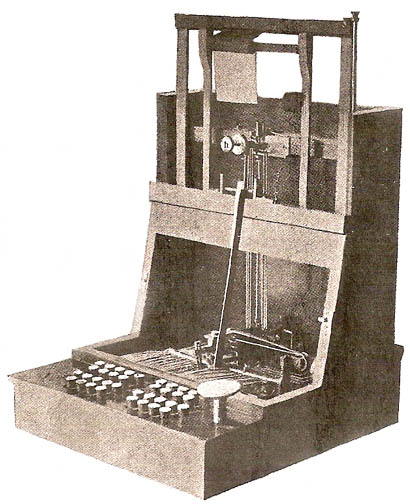

If we really want to dig further back into the history of the ‘typing’, we would find that the typewriters of the kind that we wouldn’t really feel comfortable using these days, were around since 1714.

In the later years, the machine got reinvented by several innovators to bring in ease and productivity.

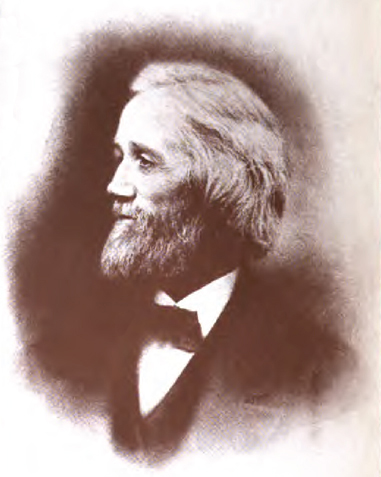

However, the credit of introducing the typewriter on a large commercial scale historically goes to Sholes, who invested almost all of his life and efforts in making his layouts of the machine a part of human life.

Sholes was first struck by the typewriter during his time as an editor of a newspaper in Milwaukee, where he tried to build a machine for typesetting, however, he failed miserably and later abandoned the idea altogether.

However, he couldn’t stay away from typewrite for too long and with the help of a fellow printer Samuel W.

Soule he successfully designed and patented a numbering machine in 1866.

This machine was able to print number for pages on books, tickets, and other such items.

Soon after that Sholes and Soule had the opportunity to present their machine to a lawyer and amateur inventor Carolos Glidden, who initially liked the machine but thought it would have been a much more productive machine if it had the ability to produce words rather than just number.

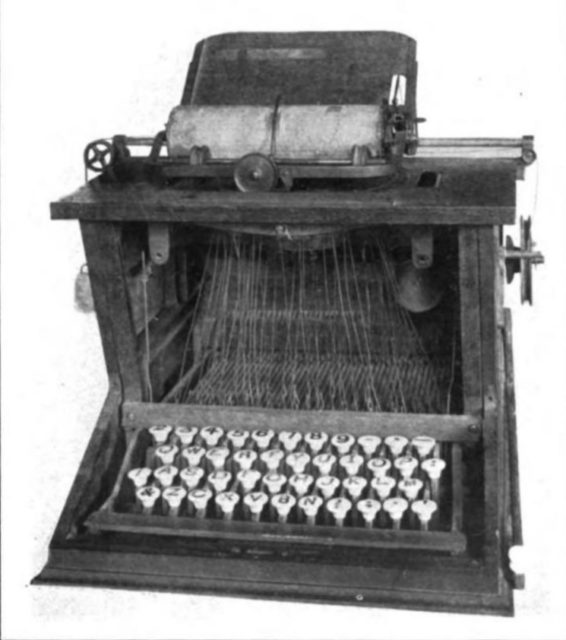

Sholes quickly picked on the idea and set to work; he thoroughly brainstormed for all possible options to reinvent his machine as a fully functional word producing the machine.

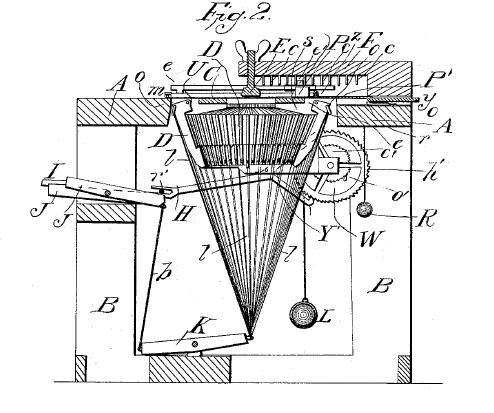

Sholes finally hit the jackpot in 1867 when he came across an article in Scientific American, wherein a prototype of the machine by John Prat called ‘Ptertype’ was illustrated.

Sholes analyzed the prototype and thought he could innovate on that prototype with some changes and could use it for his machine.

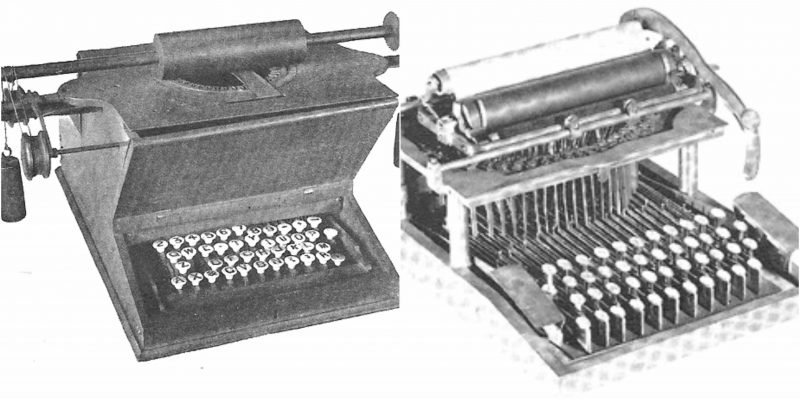

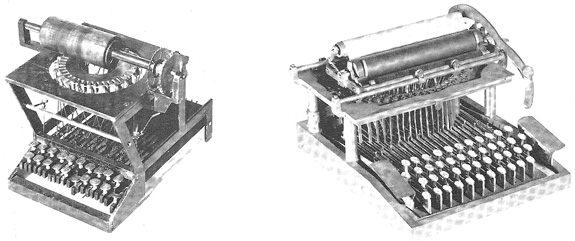

Glidden joined Sholes and Soule in their new endeavor and soon the trio came up with a machine Sholes dubbed the ‘typewriter’ but others started calling it the ‘literary piano’, due to the basic two rows of white and black keys.

The keyboard didn’t contain the numerals 0 and 1, as the letters l and O were deemed sufficient for the task.

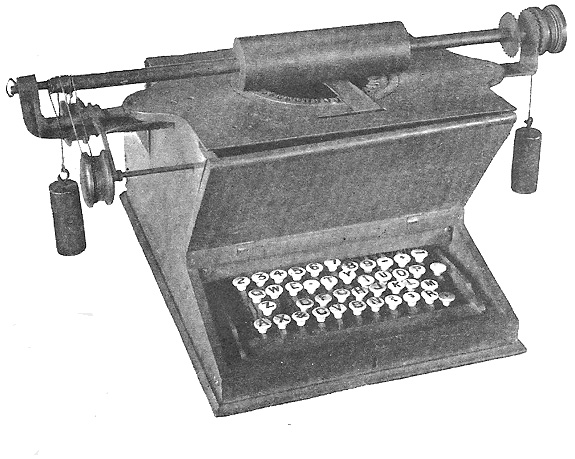

The next five years were especially tough for Sholes as he spent days and nights trying to perfect his layout by a series of trial and error rearrangements.

Sholes also benefited from the study of bigram frequency by Amos Densmore who was an esteemed educator and brother of the financial backer, James Densmore. A number of changes were made in the following years primarily to make the typing experience less stressful for the user.

The QWERTY system emerged after a number of changes and Sholes left it at that as he thought the height of editing had been reached.

The new layout had the words all spread out across the keyboard, so the typist had to alternate his fingers while typing reducing the risk of strain and also minimizing the risk of typing bars collisions.

As the use of the new QWERTY system became more and more prevalent, the masses became used to it and making any more amendments seemed impracticable.

So now here we are now, with the QWERTY layout that has taken over our communication systems on the PCs and now on smartphones.