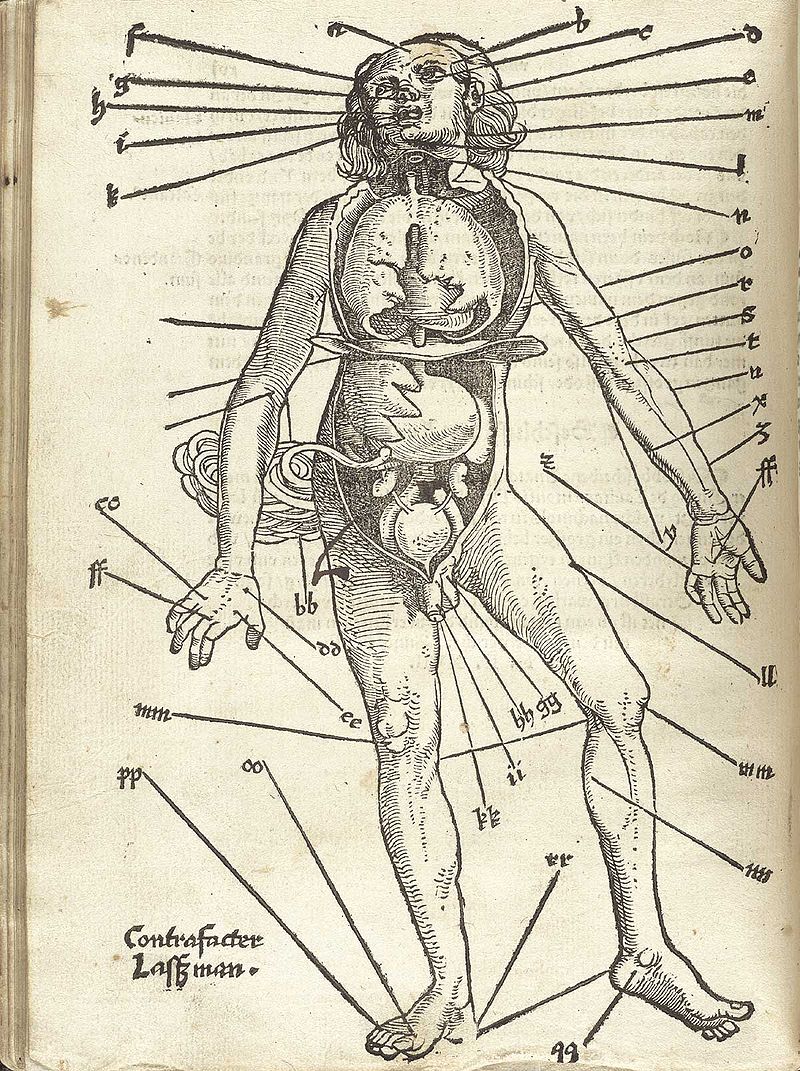

During the Medieval Ages, it was believed that the health of a person’s body depended on the so-called four humours: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. People believed that if one of these humours was out of balance, the person was ill. The most popular method for curing the illnesses was bloodletting.

At the beginning, the bloodletting was performed by clerks. In 1215, the Pope issued a decree which forbade clerks to take part in any shedding of blood. Patients that needed bloodletting were sent to the barbershops.

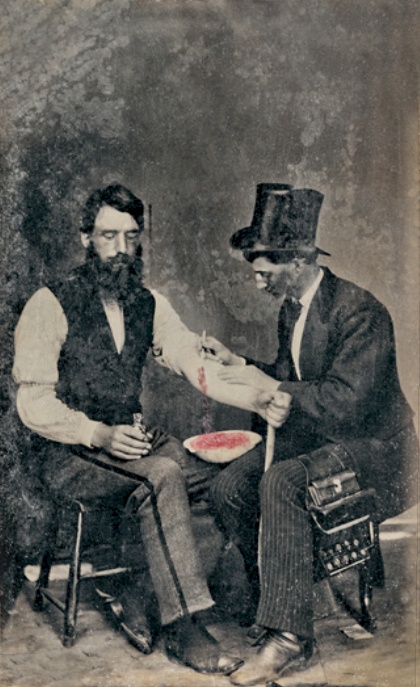

Barbers had the equipment needed for performing bloodletting. Besides cutting hair, they could pull teeth, amputate limbs, and administer leeches. As the barbers knew how to use a razor, it was presumed that they would be skillful in carrying out any treatment that involved cutting the skin, and so the practice was passed over to them.

Blood was removed from the patient’s body by using tools such as lancet (a small surgical knife with a sharp point). Depending on the condition of the patient, different amounts of blood were drawn from the patient’s body. During the procedure, the patients were given a pole which they gripped in order to make their veins bulge.

The blood was kept in shallow bowls or flint glass cups which barbers placed on the windows of the barbershops. The used bandages were hung on the barber’s pole in order to advertise the services that the barbers offered. Today the barber’s poles have red and white stripes which represent the blood and the bandages.

A great number of surgeons who performed bloodletting were wiped out by the Black Plague during the 14th century. This increased the number of patients who turned to the barbers seeking for help. There were many barbers who set tents in different towns where they offered their services. They were called ‘The Flying Barbers’.

The barbers and the surgeons operated in different medical guilds until 1540 when king Henry VIII united the two guilds into one company named ‘The Company of Barber-Surgeons’.

Barbers knew how to make a bloodletting, but performing more complicated surgeries was just too much for them. People started to complain that barbers made them feel sick instead of well. Barbers could not compete with the surgeons anymore.

Ambroise Pare, who is known as the father of the surgery, raised the professional status of surgery. After this, barbers were no longer allowed to perform any surgical procedure except bloodletting. This lead to separation of the two companies in 1745 by an act of parliament.

The bloodletting method was spread through America by the European colonies. Many Americans preferred this method for curing their diseases. George Washington, the first president of the United States, died after having 3.75 liters of blood removed from his body within a 10 hour period as a treatment of throat infection.

By the 19th Century, barbering was completely separated from medicine and began to emerge as an independent profession. The bloodletting method was still performed, but it killed far more people than it cured.