On September 20, 1854, the SS Arctic sailed from Liverpool en route to New York City. The SS Arctic was one of four sister ships, along with the Atlantic, Baltic, and Pacific, built by American tycoon Edward Knight Collins, along with two financial backers, James and Stewart Brown of Brown Brothers and Company, a Wall Street investment bank.

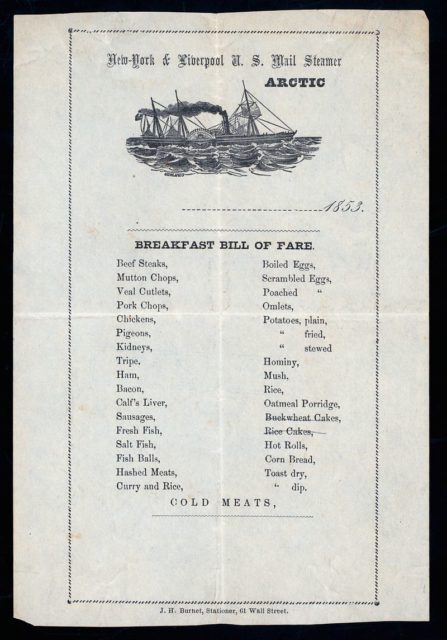

The four magnificent paddle steamers, named after great oceans of the world, were built to gain transatlantic supremacy against the British Cunard Line. Collins was determined that his luxurious steamships would not only scoop the luxury travel market between America and England but would also receive the subsidy that the US Government was paying to Cunard for carrying the mail.

The SS Arctic was built in New York City in the William H. Brown shipyard and was launched in 1850 on the East River in New York. She was destined to carry wealthy passengers who could afford the luxurious accommodations and other amenities available on board. In addition to carrying passengers, the Collins Line had won the contract to carry the mail between New York and England and received a lucrative subsidy from the American government.

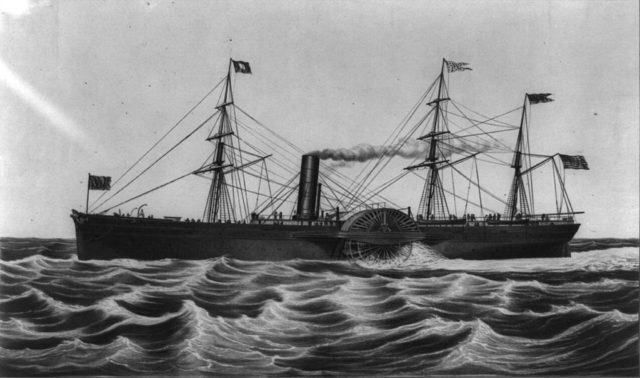

The SS Arctic was an enormous ship for her time, at 284 feet long and almost 3,000 tons in weight. She had a wooden hull, and her two side-lever steam engines, which accounted for almost half of the entire construction cost, powered two huge paddles located on either side of the ship. The cost of these ships was subsidized by the US Government, and they were built in such a way as to allow easy conversion to warships should the need arise.

The SS Arctic was captained by James F. Luce and entered service for the Collins Line on October 26, 1850. She regularly plied her route between America and England and she quickly established a reputation for both speed and comfort. Her crossings were normally undertaken in 10 days and in February 1852, she arrived in Liverpool some nine days and seventeen hours after leaving New York.

This was considered an exceptional achievement for a crossing of the Atlantic at any time of the year, but the fact that it was accomplished in winter made the feat all the more admirable.

The traveling public adored the ship, and she was nicknamed The Clipper of the Sea in honor of her speed and reliability, but this reliability came at a great cost to the Collins Line. The massive power of the steam engines strained the wooden hull, resulting in huge maintenance costs. In July 1854, the Collins Line replaced her aging engines with newer, more fuel-efficient engines in the hopes of slashing their running costs. It was reported by the Baltimore Sun that the new engines, produced by Wethered Brothers, a Baltimore firm, would reduce the fuel costs by half.

Continues below

Last Voyage of the SS Arctic

On September 20, 1854, the SS Arctic sailed from Liverpool on what should have been a routine trans-Atlantic crossing. Later, it was estimated that she was carrying approximately 400 souls, 250 of these were passengers and 150 crew. Among the passengers were Mary Ann Collins, the wife of the line’s founder, and their two children, as well as members of the Brown family. Also on board was Willie Luce, the captain’s son.

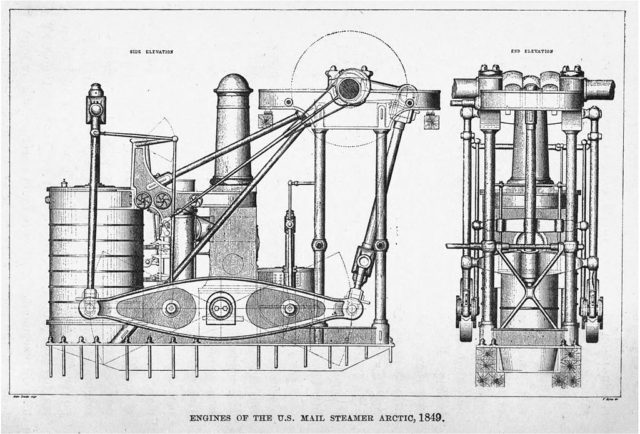

For a week the voyage progressed normally, with passengers enjoying the luxury afforded by the great ship and the crew carrying out their normal duties. On September 27th, during the earlier part of the day, the ship was sailing over the Grand Banks, off the coast of Newfoundland in Canada, when dense fog rolled in. This area is renowned for fog since the warm air from the Gulf Stream collides with cold air from the north, frequently resulting in thick banks of fog.

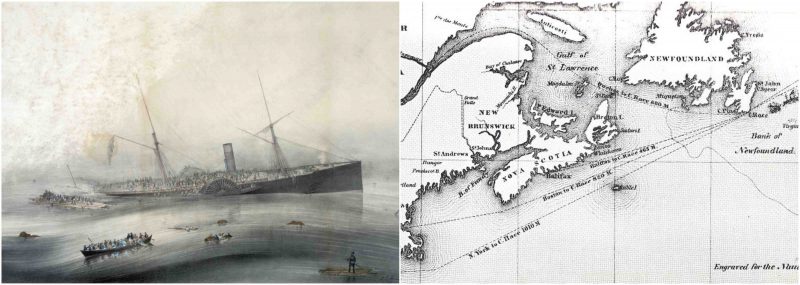

However, the captain was experienced in sailing these waters and had posted the crew to keep a lookout for other vessels. Just after midday, the lookouts shouted a warning, but it was too late and the SS Vesta, a smaller vessel carrying French fishermen back to France from Canada, having come to the end of the summer fishing season, slammed into the bow of the Arctic. Before snapping off completely, the steel hull of the Vesta tore a mighty gash in the wooden hull of the Arctic. Captain Luce’s first idea was to go to the aid of the Vesta, being convinced that the ship was mortally damaged, but the Vesta had watertight compartments which saved her from sinking; she eventually made it safely to Port St. Johns in Newfoundland.

Captain Luce was then told that the Arctic was seriously damaged below the water line and that she was taking on water. He immediately turned towards land in the hopes of making it to safety, but the water level crept up inside the ship and water eventually reached the engine room. The boiler fires were extinguished, leaving the vessel powerless.

The captain instructed the crew to commence abandoning ship. The Arctic carried six lifeboats that were only able to carry 180 people so; at the least, a high number of the passengers should have found a place on the lifeboats, but the crew began to panic, and their discipline was lost. The lifeboats were haphazardly launched, and most of the places were taken by men and members of the crew. The other passengers were abandoned to their fate and tried to cling to pieces of wreckage or makeshift rafts.

Captain Luce was incensed at the behavior of his crew and tried to bring discipline to the chaos. He refused to leave his ship and went down with the vessel, standing on the box covering one of the huge paddles. Strangely enough, this saved his life, as the wooden box came adrift and popped back up to the surface with the captain clinging to the wreckage. He was picked up by a passing ship.

![Map (1854) showing the position of the collision (upper right) between the Arctic and Vesta, (roughly 46° 45’N, 52° 06’W)[29] and the relative positions of land: Newfoundland, Halifax, Quebec, and New York.](https://www.thevintagenews.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/65/2017/02/35-640x343.jpeg)

The lifeboats that were launched carried 24 male passengers and approximately 61 members of the crew. Of the six lifeboats launched, two eventually reached the Newfoundland coast, and one was picked up by a passing ship; the remaining three disappeared without a trace.

Public Outcry

As the survivors made landfall in Canada and the news of the disaster spread two weeks later, there was a huge public outcry at the behavior of the crew and the fact that every woman and child had perished while just under half the crew survived.

Newspaper stories lambasted the crew and the surviving male passengers for allowing the women and children to perish, and the only person who gained any credit for his actions was the captain. Captain Luce was hailed as a hero and lauded on his rail trip from Canada back to New York. Many of the surviving crew members never returned to the United States.

Though there were calls for an official inquiry into the sinking, none was held, and no one was ever called to account for the disaster. Captain Luce retired and did not go to sea again.

The outcry over this disaster was so great that it led to the tradition of allowing women and children to board available lifeboats first during a maritime disaster, a tradition that is still in place today, About Education reported.

A monument to this disaster stands in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn in New York. The marble monument depicts the sinking of the ship, and is dedicated to those members of the Brown family that died in the disaster.