The concept of money has changed a lot since it was first introduced, but in its essence is still more or less the same: Those who have more money are always in a better position than those who possess less. We are still using a somewhat dated monetary system based on paper and coin money although, slowly but surely, we are moving into the age of digital money, with payment methods such as cryptocurrencies taking a huge upswing. But a long time ago, before Bitcoin, before normal coin, when people felt the need for a commodity exchange system, people started using “shell coin.” Yes, for a very long time, sea shells were used as currency on almost every continent.

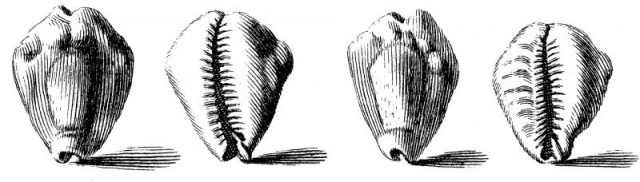

Shells, among other things, got their place in trade as a product for commodity exchange, mainly because of their value as body ornamentation. Besides this, they had some other attributes that made them a perfect basis for an early version of a monetary system. Among the variety of shells that were used as coins in different parts of the world, there was one type that had a huge international demand, and that is the shell of the money cowrie, Cypraea moneta.

When you look at a cowry shell, it is easy to see whey they were chosen to serve as money and later, in some places, even became as valued as metal coins. First of all, they are durable and handy. Their strength is great, and they are small and light, which makes them easy to handle and transport. Also, these shells are easily recognizable. They are unique, and their specific shapes and distinctive texture is the best protection against forgery. All of these attributes are comparable to modern-day money. No wonder people decided to use them for the same purpose back then.

The money cowry is native to the Indian and Pacific oceans, with an extremely high population in the waters around the Maldive Islands, just southwest of India. At one point, because of the closeness to this valuable natural resource, a whole sea-shell industry was born on the Maldives. Men, women, and children were all engaged to collect and prepare the shells for trade. First of all woven mats made of coconut tree branches were placed on the surface of the water. Baby mollusks gathered on the mats and later the mats were taken out of the water to dry. After drying, the shells were polished, graded, and exported, mostly from Bengal which was a major trade hub at the time.

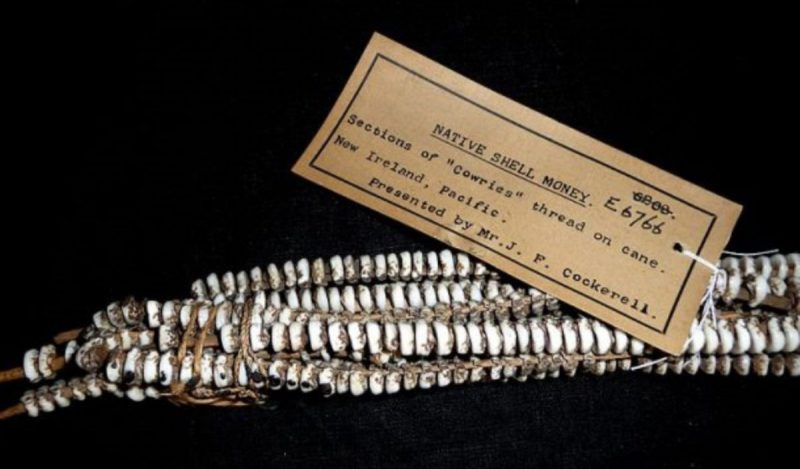

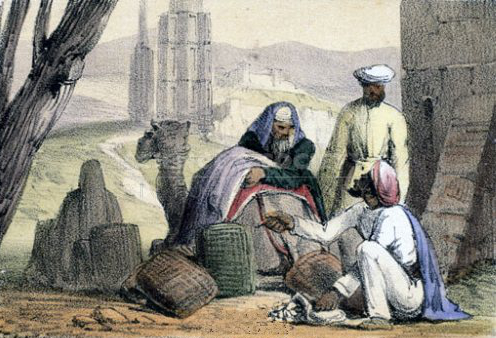

Depending on the place of trade, cowry shells were either hung on strings to be valued separately, or loaded in buckets to be sold in larger quantities. In Bengal, for example, sea shell payments were made with baskets full of shells. Each basket contained around 12,000 cowry shells.

Although the Maldives was an important cowry money source throughout history, the use of cowry shells as currency, which according to some researchers is the oldest form of currency, originated in ancient China. Several thousand years ago, Chinese people needed an efficient currency that could be used for trade in all parts of their huge empire. They chose cowry shells because they were hard to counterfeit, but most importantly the sources of cowry were far away from China, and they were not easily obtainable. This meant that only the richest people could obtain bigger quantities of this commodity.

The use of cowry money in China is well documented. Engravings on bronze objects, the oldest of which dates from the 13th century B.C., inform us about the monetary usage of shells. During excavations in the tombs of some early emperors, it has been found that they were buried with a cowry shell in their mouth. In fact, cowry shells are so deeply embedded into Chinese culture that many characters in written Chinese language that refer to money or trade, contain the symbol for cowry shell: 貝.

Traders from the Arabian peninsula introduced cowry shells from India to markets in Africa, and they soon spread across the whole continent. When Portuguese, English, French, and Dutch traders and explorers saw the potential of this currency, they started to accumulate great quantities of shells which they used for trading slaves, gold, and anything else of value to them. This caused a huge imbalance in the regional trade system. The import of cowries along Africa’s west coast caused the disappearance of many local currencies. On the other side, India was left with a huge cowry shortage throughout the 17th century.

Cowry shells reached many places around the Earth, even those that were very distant from the main sources. The usage of cowry shells in trade has also been recorded in North America. The Ojibwe (Chippewa) peoples that used to live around Lake Superior used cowry shells for trade and in their ceremonies. It is strange how these shells arrived there, so far North, where they are not usually found. According to their stories, they found them in the ground or washed up on the shores of the lake, but another theory suggests they obtained the shells through trade with some outsiders.

It is obvious that shells were used as money and that they did the job pretty well, but one question remains: how did people determine their true value in comparison to other goods? Well, it is quite simple. Their value was determined by the law of supply and demand which lies at the foundation of economy as a science. The farther the place was from the source of cowries or a big trade center, the bigger value the cowry carried. This meant that in some places where it was valued more, you could buy a cow for only one cowry, while in other places, where the shells were more abundant, one cowry had no value. In the Maldives, for example, a person needed thousands of shells to exchange them for only one gold coin.

In some places, such as Papua New Guinea, cowry shells were used in more ceremonial ways, and often to settle disputes between two or more parties. The cowries that were used in these instances were kept safe as they carried a history (they became artifacts) and their value grew as well.

Another method of putting a value on the shells that were used in different places is based on the fact that polishing and working shells is a demanding and time-consuming process. Therefore, the more work was put into the shells, the more value they had. Those who are familiar with the process of Bitcoin mining today would notice that this sounds very similar to the “proof-of-work system.” It is the same principle that we use today but invented thousands of years earlier.

The role of cowry shells as currency remained until the middle of the 20th century, which shows us how efficient and stable this ancient system was. Today, in some places such as the island of East New Britain (Papua New Guinea), cowries are still used as currency, but this is purely nostalgic. A way to remember part of the history. In another part of the world, in Bamako, Mali, the usage of cowry is recorded on the facade of the building of the Central Bank of West African Countries.

Related story from us: The oldest examples of jewelry was made from sea shells

The Bitcoin analogy mentioned above shows us that the most functional system is the one that is the most basic and simple. This is not the first time that humanity learns from the past and it won’t be the last. Our past is more than just stories about wars and conquerors and dividing and ruling; our past is an open book about us as species and the way we evolve or devolve.