In spring 1921, USS Conestoga, a tugboat assigned to the United States Submarine Force, went missing somewhere in the Pacific, while on its way to American Samoa. The tugboat steamed out from Mare Island, California, together with a coal-transporting barge on March 25th. It was to stop at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, for refueling, but something happened along the way.

As it became clear that the had ship broken contact and that it must have encountered a problem during its voyage, a search party was dispatched from the Pearl Harbor military base in early May. Experts have estimated that Conestoga must have been somewhere around 100 nautical miles southeast of the coast of Hawaii.

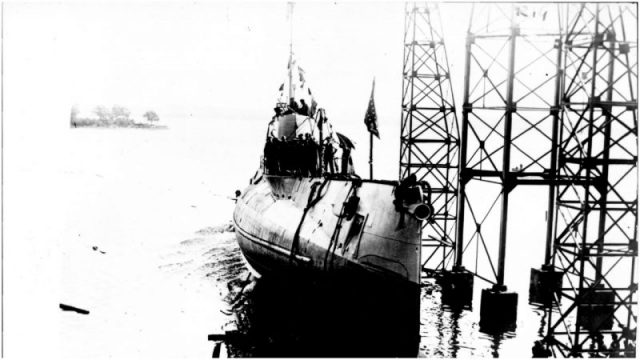

A submarine designated USS R-14 (SS-91) under the command of Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas was sent out in order to conduct a surface search, in hopes of rescuing the tugboat and its crew.

However, during what looked like a standard search and rescue mission, they were met by a strange twist of fate. The crew of the submarine very soon found encountered a situation where they were the ones in need of saving.

Having incorrectly estimated the amount of fuel needed for the mission, when they arrived at the spot where Conestoga was presumed to be, the submarine had run out of usable fuel.

Since its electric motors lacked enough battery power to transport them back to base, they were stranded some 100 nautical miles from Hawaii, caught in a desperate situation. To make matters worse, their radio had malfunctioned and all communication went silent. On top of it all, the limited food supply wasn’t going to hold out for more than five days.

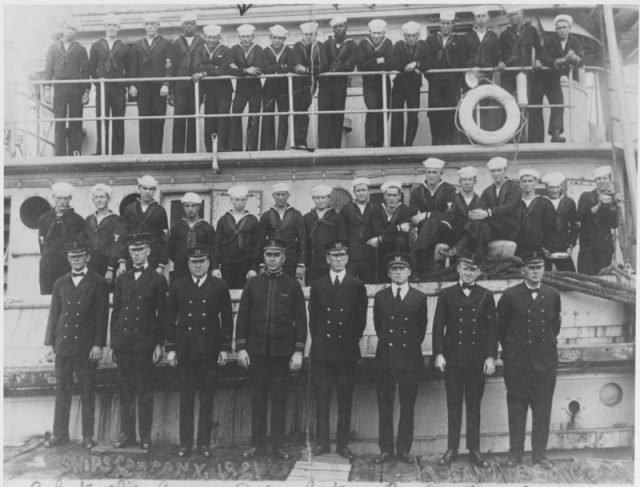

They were out in the open sea, with no fuel and no means of letting their headquarters know in what trouble they were in or where were they stranded. The crew consisting of 27 men and two officers were getting restless, as their situation seemed unresolvable.

That was until the submarine’s engineering officer Roy Trent Gallemore decided to think outside the box. Gallemore realized that they were, in fact, surrounded by a power source used by mariners for thousands of years.

The ship’s engineer came up with an idea to use the wind to power the submarine.

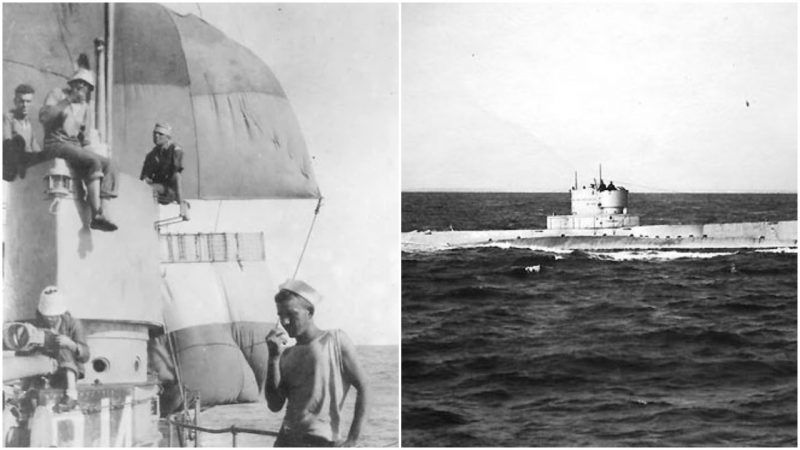

All hands were soon employed in making a foresail out of the crew’s hammocks. Eight hammocks were stitched together, forming a sail, held by a frame made from dismantled bunks. The entire structure was then tied to the vertical kingpost of the torpedo loading crane, located forward of the submarine’s superstructure.

However, a submarine was much heavier and had a much lower silhouette than let’s say a 16th-century Spanish galleon. With the foresail, it achieved a speed of no more than one knot (1.2 mph; 1.9 km/h).

7 Greatest Shipwreck Treasure Ever Discovered

So Lieutenant Gallemore decided to produce additional sails in order to gain speed. His do-it-yourself approach certainly motivated the sailors who were just several hours earlier contemplating their impending doom.

They built a mainsail out of six blankets and attached it to the radio mast, which added another half a knot to the total speed of the ship. In addition to this, another half a knot was achieved by stitching up another eight blankets and assembling yet another frame out of bunk beds.

The third sail was then added to the vertically placed boom of the torpedo loading crane.

Traveling at a speed of almost three knots, Gallemore was able to start recharging the batteries of the electric motors. After 69 hours of sailing, they finally reached the easternmost tip of the Hawaii islands and entered Hilo Harbor on the morning of May 15, 1921.

For the achievement and spirit of innovation, Lieutenant Douglas received a letter of commendation from his Submarine Division Commander, CDR Chester W. Nimitz.

USS Conestoga, on the other hand, wasn’t so lucky.

The tugboat was officially declared missing on June 30, 1921, but it was not until 2009 that a shipwreck was discovered a few miles from Farallon Island, just off the coast of California.

In 2016, the location of the shipwreck was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online, The Vintage News, and Taste of Cinema. His main areas of interest are history, particularly military history, literature and film.