Andrei Sakharov was born on the 12th of May, 1921, in Moskow, Russia, into a family of a cultured and liberal intelligentsia. His father was Dmitri Ivanovich Sakharov, a private school physics teacher, and an amateur pianist, and his grandfather was a prominent lawyer in the Russian Empire.

Andrei studied physics at Moscow University, and he was one of the most brilliant students there. He was exempted from military service during World War II, and completed his studies in 1942. When he finished his studies he worked in an armament factory as an engineer, where he patented several inventions. Later, when World War II ended, he was recruited into the top-secret nuclear weapons project. He is known as the father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb.

He wrote a pioneering article on the effects of low-level radiation in 1957 because he was concerned with the radioactive hazards of nuclear testing. In 1961, he opposed to Nikita Khrushchev’s plan for an atmospheric test of a 100-megaton thermonuclear bomb, fearing the hazards of widespread radioactive fallout. Despite his warnings, the bomb was tested on October the 3rd, 1961.

In 1968, Sakharov finished his essay “Reflection on Progress, Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom” that was published in The New York Times. He emerged dramatically in the human-rights struggle and became the movement’s inspiration. In his essay, he warned of grave perils threatening the human race, called for nuclear arms reductions, predicted and endorsed the eventual convergence of communist and capitalist systems in a form of democratic socialism and he also criticized the increasing repression of Soviet dissidents.

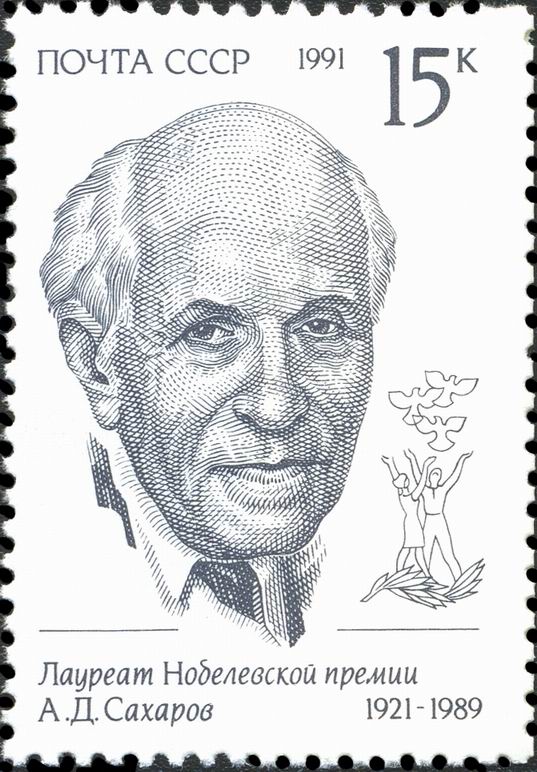

The Soviet Union banned him from pursuing further military work because of his social activism in the sphere of human rights and other causes. His social activism made him a Nobel Prize Winner, and in 1975 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. The Nobel Committee had many reasons for awarding him the prize, and as it is noted by the Nobel Prize Committee:

“Sakharov’s fearless personal commitment in upholding the fundamental principles for peace between men is a powerful inspiration for all true work for peace. Uncompromisingly and with unflagging strength Sakharov has fought against the abuse of power and all forms of violation of human dignity, and he has fought no less courageously for the idea of government based on the rule of law. In a convincing manner, Sakharov has emphasized that Man’s inviolable rights provide the only safe foundation for genuine and enduring international cooperation.”

Sakharov won international respect criticizing human rights violations and calling for the release of prisoners of conscience. But in the Soviet Union, he was considered as a state enemy and on January the 22nd, 1980, he was banished to Gorky, 250 miles east of Moscow, because he denounced the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan in December 1979.

His wife became his only link to the outside world, serving as his envoy to bring to Moscow and abroad Sakharov’s statements on important political issues, among them “The Danger of Thermonuclear War” that was published in Foreign Affairs in 1983.

Finally, in December 1986 the new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev released Sakharov and his wife Yelena G. Bonner and they returned to Moscow and to a new Russia.

In his last years he met with world leaders, he had press interviews, he traveled abroad and he renewed contacts with his scientific colleagues. In 1989, he was elected to the First Congress of People’s Deputies, representing the Academy of Sciences. He witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall and the beginning of irreversible changes that swept Russia.

Andrei Sakharov died on December the 14th, 1989, at the age of 68.