Back in the 1830s, in America, the expansion west into new territory was hampered by the terrain and climate faced by many of the pioneers and settlers. In the southwest, in particular, the deserts, impassable rivers, and mountains were proving to be nearly impossible to cross by people and animals alike.

US Army Lieutenant George Crosman studied the problem and came upon what he thought was the ideal solution. When researching appropriate beasts of burden, he discovered the camel.

These creatures were known for carrying heavy loads, being able to traverse a variety of terrains, and could travel many miles a day with little water and food. Unlike horses, they didn’t require shoeing, and they had a reasonable speed of travel. Initially, his report was disregarded by the War Department, but the seed of an idea was sown.

The idea of using camels remained unexplored until 1847 when Crosman met Major Henry Wayne from the Quartermaster Department, and between the pair of them, another report was submitted to the War Department which resulted in Congress recommending camels be imported.

Eventually, in 1853, the idea of importing camels was put in front of President Franklin and the Congress. After years of tossing the idea back and forth, Congress finally agreed to pass the Shield Amendment that stated a sum of $30,000 should be used to purchase and import camels for military purposes.

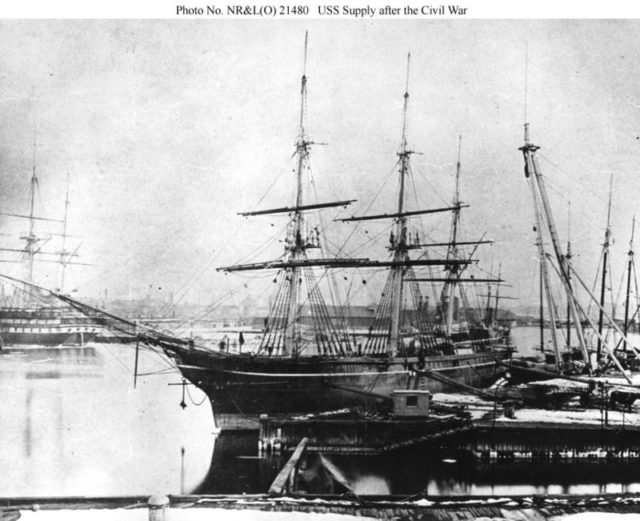

A Navy store ship called the USS Supply was altered for the camels with special slings and stable areas. Zoos were visited, and military men and scientists were interviewed to gain knowledge about camel handling. This was all done by the commander of the ship, Lieutenant Davis Porter, who had such an eye for detail he was leaving nothing to chance to get the camels they were going to purchase safely to the U.S.

Once the USS Supply arrived in the Mediterranean, they discovered it was harder than they first thought to purchase healthy camels.

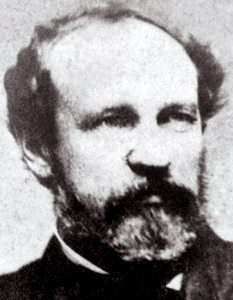

However, through persistence and local help, they eventually bought and received as gifts a total of thirty-three animals. They were a variety of camel, including Bactrian (two humps), dromedaries (one hump), and some Arabian camels.

They were pleased with their selection, as the Arabians were known for speed and the Bactrians for their load carrying. The cost was an average of $250 per animal, and after hiring five Arab and Turk natives to help care for them, they were soon sailing back home.

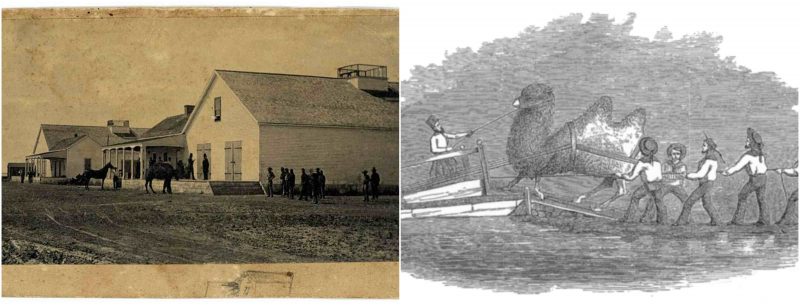

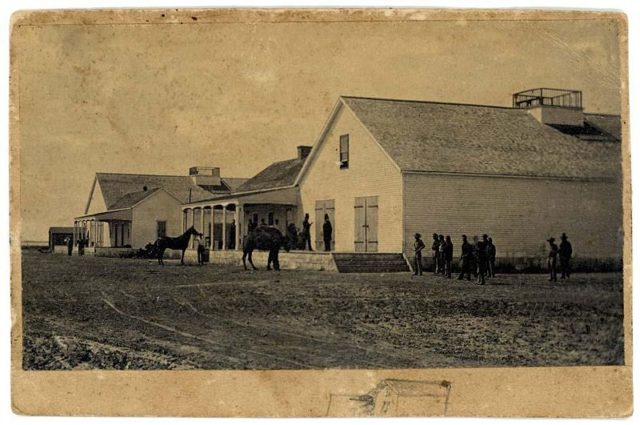

Camp Verde home of camels

Camp Verde would become the home of the camels for many years. To prove the camel’s worth to skeptical military members, Wayne devised a test.

He sent a mule team to fetch oats from San Antonio with three wagons drawn by six mules each. Each wagon carried 1,800 pounds of oats. It took the mules five days to make the return journey. He then sent six camels, and they carried back 3,648 pounds of oats each and completed the journey in only two days. Many tests were conducted comparing the carrying capabilities and speed of the camels compared to that of horses.

For many months Wayne worked with drovers and soldiers so that everyone would understand these beasts. They not only had to learn how to feed and care for the animals but also how to manage the camel saddles and how to deal with their temperament. When treated well a camel is a docile animal, however, if mistreated at all it will kick, bite, and stomp its attacker, sometimes to death. As with a cow, camels chew the cud, and they have a disconcerting way of spitting their cud at anyone who annoys them.

Camels used in surveying

A further forty-one camels arrived in 1857, which was a good thing as five of the originals had died of disease. The US military now had a total of seventy camels. Congress decided to conduct a survey to build a roadway due to pressure from citizens. It was to be built along the thirty-fifth parallel from Fort Defiance to the Colorado River on the Arizona/California border. Mr. Beale, who won the contract, was ordered to take twenty-five camels on the expedition. The camels took a few days to adjust to the journey due to having been idle for so long. Beale soon became impressed with the camels in his party as they were soon able to outdistance the pack horses and were able to travel over terrain that the other animals struggled with. Beale was impressed that the camel ate very little of the forage material packed to feed the animals and that they were happy to eat scrub and plants found along the trail.

They showed their worth when the party got lost. For thirty-six hours the lack of grass and water made the mules upset, but a small party of camels set out and found a river and saved the expedition. From that point on, the camels were used to hunt sources of water for the expedition. Finally, they reached the last hurdle, the Colorado River. Everyone believed that camels couldn’t swim, so Beale was surprised when the first camel was led to the river – it swam happily across, fully loaded. In the crossing, they lost no camels but did lose two horses and ten mules. The whole expedition had lasted four months and covered a staggering twelve hundred miles of terrain.

Beale was so pleased with the camels he refused to return them to Camp Verde and moved them to his business partner Bishop’s ranch in San Joaquin Valley. He continued to use the camels for his personal business of hauling freight. Once, while hauling freight, Bishop was threatened by attacking Mohave Indians. His men mounted the camels and charged. This was the only combat the camels ever participated in, and somewhat ironically, it wasn’t military but civilian. Beale continued to use camels to survey routes for new roads, and he was always full of praise about them. By this time there had been a change of government; they were willing to fund the camels they had but weren’t interested in purchasing more.

First official military testing

It wasn’t till 1859 that the Army did their first official test of camels. The army wanted to see how they would do against the existing express service for carrying messages. They had to run for three hundred miles from Camp Fitzgerald to Camp Mohave; only two test runs were made, and in both cases, the camels died of exhaustion.

This was the only test the camels had ever failed, as they were no faster than the mule service, but the “camel express” was fatal to any camels involved. In early 1861 another test was conducted to assist the Boundary Commission with their surveying expedition. The survey was very unorganized, and if they hadn’t taken the camels, all lives would have been lost when they wandered into the Mojave Desert, About Education reported.

The camel experiment ended with the start of the Civil War. Rebel troops captured Camp Verde, and the camels suffered badly, with some being killed outright. The remainder of the camels at Fort Tejon were eventually sold by public auction as no one knew what to do with the animals, in large part because of a lack of awareness of the positive reports about them. The camels ended up living on private ranches, being sold to circuses and working as pack animals for miners in the backcountry. Many camels were eventually turned loose and lived wild in the deserts and plains of the Southwest U.S.

Here is another story from us: Ancient Romans used flaming war pigs to counter elephants

It is unknown if they still roam wild, with the last credible sighting being back in the 1940s, but there have been unconfirmed sightings of these noble beasts as recent as the 1980s.