She was born around 1350 B.C., the child of Queen Nefertiti and her husband, Akhenaten, within Egypt’s tumultuous 18th Dynasty, which has produced several names for history. Her name was Ankhesenamun, and before turning 13, she was already wed to her father, possibly also becoming the mother of one of his daughters.

The arranged marriage with her father was only the beginning of Ankhsenamun’s royal entanglements. Her fate was to later marry a half-brother: the famous boy King Tutankhamun. She was still a teenager at the time of her second marriage, and she outlived both her first and second partners. But Ankhesenamun’s later life, following the death of King Tut, reveals some surprises too, and some blank spaces. Her biography is not complete, including the year of her death and whether she was killed as a punishment or died a natural death.

Recently archaeologists have been surveying an area in Egypt, the so-called Valley of the Monkeys, which, as rumor has it, might also be concealed the final resting place of Ankhsenamun. Finding the grave of this important woman of the ancient Egyptian royal family might finally fill in the gaps of what exactly happened during her last years within the 18th Dynasty of Egypt and explanations for these confusing relationships.

Archaeologists have proceeded with excavation in a specific area of the Valley of the Monkey where Pharaoh Ay’s tomb has been found in the past, the ruler who inherited the throne immediately after of King Tut. Sources claim it was expected that Ankhsenamun form a marriage union with this third pharaoh as well, but the Egyptian woman may have well resisted the idea and the wishes of the royal family.

Archaeologists have reportedly used radar technology to explore the specific unexplored belt of the valley and may have come across evidence of several potential undisclosed tombs that just might belong to other royals, one of them perhaps Ankhsenamun.

The efforts to survey the area progressed in the summer of 2017, Live Science reports, and as of January 2018, hundred of workers were involved in excavation efforts in the area that may include, as some speculate, the tomb of Ankhsenamun. If she indeed became the wife of Pharaoh Ay, chances are she would have been buried not too far from her last husband, experts believe.

A photograph has been released by the Discovery Channel of the ongoing excavation in the area. According to statements by the Discovery Channel for Live Science, there might be a couple of undisclosed royal tombs in the area, but we are yet to see.

The specific area where the excavations are taking place is near the famed Valley of the Kings where some of the most renowned members of the ancient Egyptian royal family have been laid to rest, including King Tutankhamon. His grave for one was unearthed in 1922, but given the story of his wife, she may have been buried in the neighboring valley.

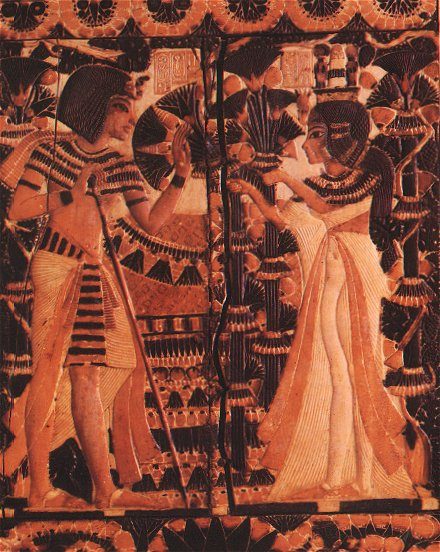

Within her first marriage, Ankhesenamun would have witnessed the reign of a somewhat controversial king in her father, one who turned Egyptian policies and religious system upside down. When her second spouse, her half-brother Tutankhamun, sat on the throne, he worked closely with advisers and policymakers to restore what was damaged by his predecessor. More evidence has it that Tut and Ankhesenamun were a good pair.

When her second husband died, Ankhsenamun was more than likely expected to marry Ay, who may have even been another relative by blood–her grandfather, incredibly enough. There is supportive evidence that his bride may have resisted the idea of their marriage. A letter has been discovered where Ankhsenamun asks the Hittites’ ruler, who oversaw a kingdom which was at war with Egypt, to arrange a wedding with one of his heirs.

The king sent a groom to Egypt–but as Smithsonian reports, this potential foreign pharaoh was killed as he tried to enter the country. The murder was carried out by General Horemheb, the same blood-thirsty general who later became a ruler of the Egyptian kingdom himself, the last reigning pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty in fact.

The incident is supposedly the last instance in which Ankhesenamun gets a mention in a historic account. A ring has been found that inscribes her name and that of Ay, something that hints the two eventually ended up in a union. More evidence is missing on whether this marriage really happened or not. Historians have not excluded a scenario in which Ankhesenamun could have been killed as well, a capital punishment for contacting the king of the Hittites and making such an erratic request with the enemy.

If the latest excavations in Egypt reveal a tomb that might belong to Ankhesenamun, archaeologists and historians could ultimately learn the details of what happened to King Tut’s wife after he died. But as Zahi Hawass, the leader of the current excavations and former antiquity minister for Egypt, explains for Live Science, there is a protocol to follow, and details of the action will not be revealed to the public until the Egyptian ministry and high-up officials grant permission to do so.