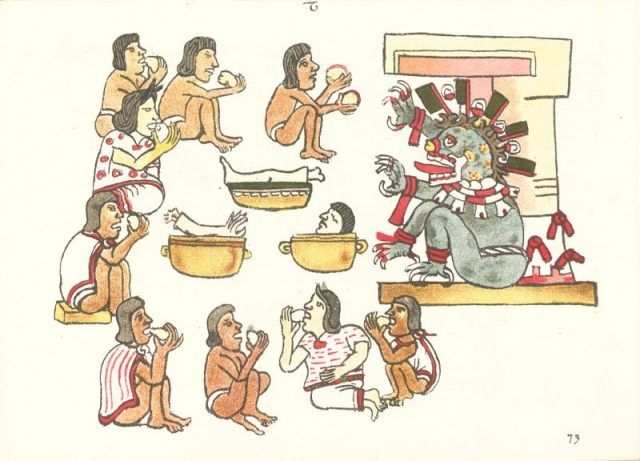

The strange phenomenon of cannibalism has, in many different forms, been around since the earliest times of human history.

While some ancient peoples resorted to this gruesome practice only during sieges and other desperate periods of scarcity, others viewed cannibalism as a vital part of their tradition or an irreplaceable ritualistic and medicinal component of their culture.

For example, in some areas of ancient Mesopotamia and India, it was believed that medicinal cannibalism was instrumental in prolonging one’s life. Gladiators in ancient Rome were known to sometimes drink the blood of their defeated opponents in the hope of absorbing their vitality, strength, and combat skills.

It may seem hardly believable that medicinal cannibalism in Europe extended well into the early modern period and reached its peak in the early 17th century, at a time when brilliant historical minds such as Nicholas Copernicus, Isaac Newton, Galileo Galilei, and Johannes Kepler kick-started the Scientific Revolution.

Still, although science, philosophy, and the arts were progressively making the world a better and more understandable place, some of the crucial areas in the realms of medicine had not yet been sufficiently explored.

Things such as vaccines, antibiotics, and conventional painkillers did not exist, and people often employed what we today might consider outlandish methods to try and cure various ailments.

One of these methods was the consumption of human remains. It was believed that human blood, which was perceived as the principal life force, contained reinvigorating and rejuvenating properties.

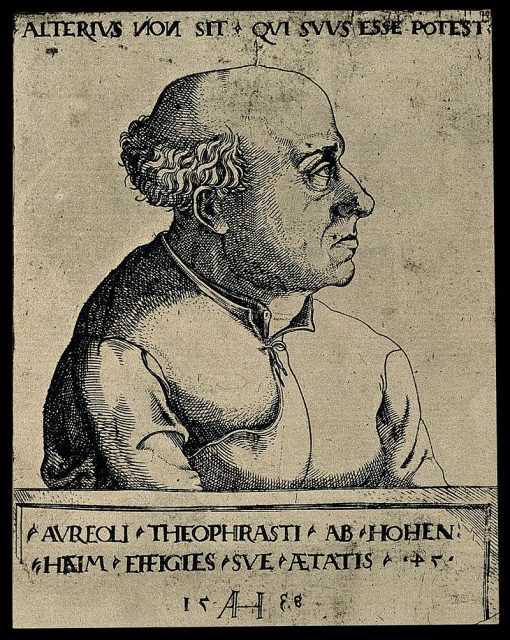

The famous Swiss-German physician Paracelsus encouraged people to attend public executions and buy a small amount of the recently deceased’s blood.

Blood was considered most valuable because people thought that it contained the pure essence of life. Fat was also commonly used. Physicians used it to treat various injuries and wounds, and many medicine vendors, who needed neither a degree in pharmacy nor knowledge of human anatomy, advertised it as a cure for all kinds of conditions.

However, although blood and fat were quite popular, nothing could have surpassed the popularity of powdered bones or pieces of mummy. Bones, especially skulls, were ground and mixed into tonics and tinctures that were perceived as potent remedies for headaches, epilepsy, internal bleeding, arthritis, and syphilis.

People of all classes were willing to rely on the efficacy of such remedies: Charles II, king of England, Scotland, and Ireland, even concocted his own tonic which was nicknamed “The King’s Drops.” It contained ground fragments of skulls mixed with alcohol and was reportedly quite popular among the aristocrats of the time.

Disturbing occasions when ancient Egyptian curses seemed to come true

Parts of ancient mummies, ground up and mixed with other substances, were highly prized for their presumed medicinal properties. Sadly, an unknown number of Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Mesoamerican mummies ended up in the digestive tracts of wealthy 17th century Europeans who believed that these preserved ancient remains contained mystical healing properties.

Because 17th century archaeology wasn’t advanced enough to accurately determine the age of many ancient artifacts, estimates tended to be based on pure speculation. People widely believed, or were led to believe, that the mummies they consumed were far older than they really were — maybe up to 20 thousand years old.

Of course, such misconceptions only added to the fascination for these mystical ancient remains; business was certainly booming for the charlatans who prepared mummy-based medicines.

With scientific breakthroughs of the 18th and 19th century and the research-oriented approach to medicine, people gradually abandoned such questionable practices in favor of remedies and procedures whose beneficial effects can be scientifically proven. Medicinal cannibalism and consumption of mummy-based medicines became a thing of the past.

Read another story from us: Mysterious disappearances in US history

However, the fact that expensive medicinal powders made from ground mummy parts appeared in German medical catalogs of the early 20th century proves that people are easily persuaded into purchasing anything labeled as “mystical” or “natural healing.”