In 1793, Scotsman Patrick Lyon arrived off the boat in Philadelphia, looking to seek his fortune and play his part in the American Dream. Philly was the home of the United States government back then, so it made sense he’d be realizing his ambitions there.

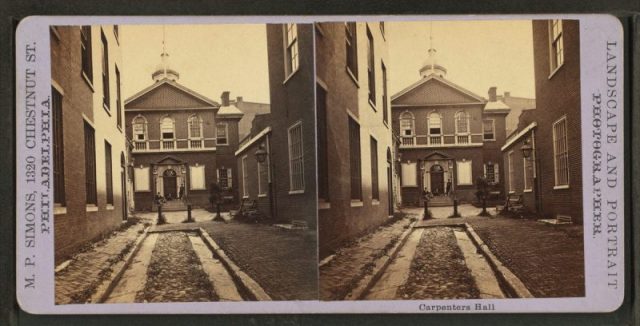

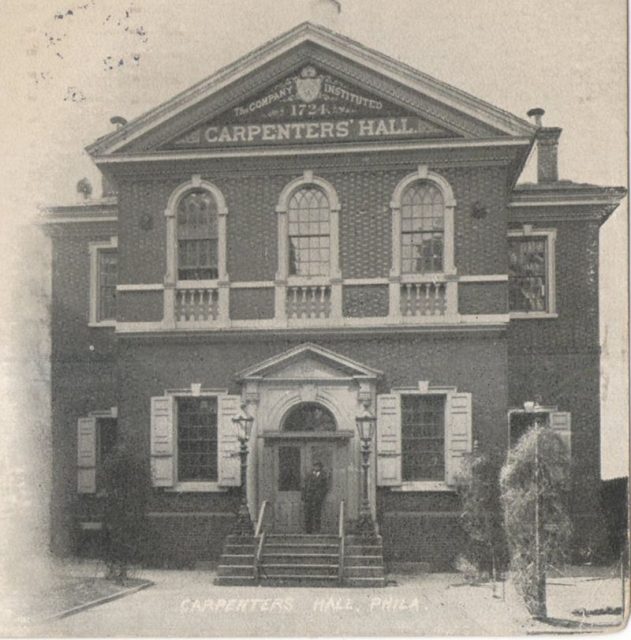

Lyon was a master smith whose skills would come to be in high demand. It didn’t start that way though. According to the website of the city’s historic Carpenters’ Hall, he “writes that his first American employer cheated him of wages. Eventually, his skill as a locksmith, blacksmith ‘and clever mechanic’ earned him a good reputation and a decent living. His work impressed many, especially his creation of an excellent fire engine.”

He probably saw that initial disappointment as a bump in the road to success. However, it wasn’t the only obstacle Lyon encountered before he finally established himself in life. Following that brush with a devious employer, he was then caught up in a situation that threatened not only his standing but his very liberty.

Five years after his arrival, Lyon was arrested and imprisoned as the prime suspect in America’s first ever bank heist.

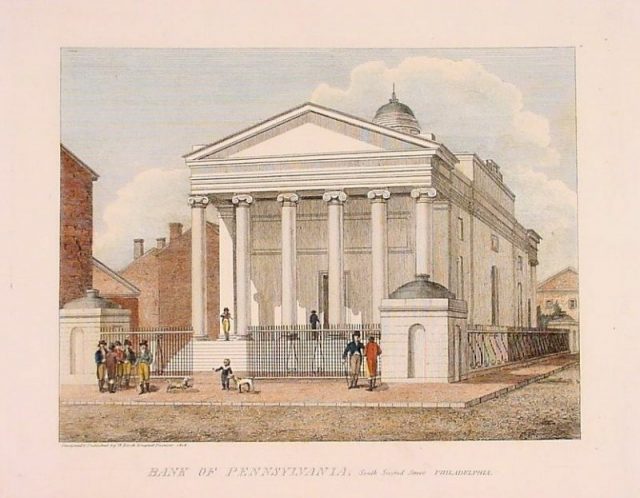

The target was the Bank of Pennsylvania, which at the time was temporarily operating out of Carpenter’s Hall. Ironically this financial institution had escaped a previous attempt to steal its contents before setting up shop to await construction of new premises.

As Saturday night became Sunday morning of August 1, 1798, $162,821 was lifted from the Bank’s vault. The news was shocking, and Lyon was in the frame because he had recently worked on the vault doors at his workshop.

High Constable John Haines saw him as the natural culprit, with the $2,000 reward playing no part whatsoever in his reasoning. The h2g2 website colorfully describes “chief suspect” Lyons as “one of those ingenious Celts from the old country who could open up the cleverest locks devised within a minute.”

Haines didn’t have to hunt Lyons down like a dog. In fact the master smith had arrived back in Philadelphia dog tired, having made a 150 mile journey on foot upon hearing of the robbery. He had his own strong suspicions about who might have committed the crime.

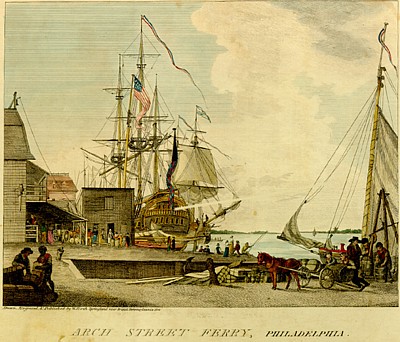

Lyons had more on his mind than criminality of course. He’d made the trek from Lewistown (Lewes), Delaware, having fled Philadelphia with his young apprentice. This was to escape a natural calamity that had engulfed the city, to which the daring heist was merely a worrying footnote.

Yellow fever had been carried across America by mosquitoes since the late 17th century. But in 1793, as Lyons made his new home in Philadelphia, so did Caribbean refugees who were carrying the notorious disease.

History.com uses the affliction’s other name when summarizing the effects. “Yellow fever, or American plague as it was known at the time, is a viral disease that begins with fever and muscle pain. Next, victims often become jaundiced (hence, the term “yellow” fever), as their liver and kidneys cease to function normally. Some of the afflicted then suffer even worse symptoms. Famous early American Cotton Mather described it as ‘turning yellow then vomiting and bleeding every way.’”

The outbreak was claiming as many as 100 lives a day, including those of Lyons’ wife and child. Evacuation was on everyone’s mind, from officials to citizens. The bereaved artisan had hoped to beat a hasty retreat, but at the last minute he was called upon to undertake an important task. A job involving the vault doors of the Bank of Philadelphia.

His new customers were Samuel Robinson and Isaac Davis. Robinson was part of the Carpenters’ Hall hierarchy and facilitated the Bank’s stay therein. As for Davis, he was a stranger to Lyons. There was an air of mystery about proceedings, with the urgent nature of the assignment being a little too urgent for Lyons’ taste.

He believed the locks and fittings were substandard and not fit for purpose. h2g2 writes that Lyons “watched Davis try the new keys repeatedly. After Lyon had finished working, he met both men at a restaurant and had an uneasy feeling that they were uncomfortable seeing him.”

Things fell into place for Lyons when he heard about the big steal, miles from the scourge of Yellow Fever. His apprentice hadn’t been so lucky and died a couple of days after they departed. The Scottish smith felt he had no option but to return to the lion’s mouth and report his suspicions.

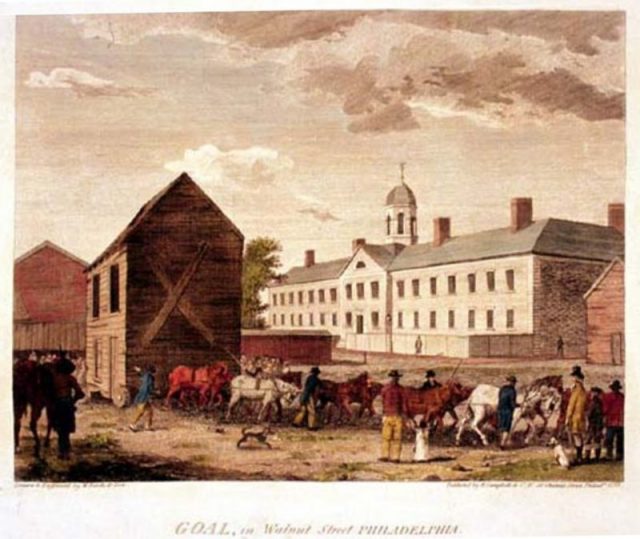

He was promptly locked up in a cramped, unsanitary environment which put him squarely in the fever’s path. Some accounts state having expended so much effort avoiding the disease in the first place, Lyons finally contracted it, though thankfully survived the experience.

Story Of A City: New York (1946)

Luck was also on his side in a way he couldn’t have foreseen. For reasons best known to himself, one of the robbers was utterly incompetent.

Isaac Davis, the stranger who had accompanied Samuel Robinson with the vault doors and taken such an interest in them, was one of two men who’d carried out the deed. The other was Thomas Cunningham, a bank porter. His role in the story is crucial but relatively short as he died from Yellow Fever days later.

Davis had begun depositing large amounts of money stolen from the Bank of Philadelphia… back into the Bank of Philadelphia. It didn’t take long for authorities to smell a rat and Davis soon confessed. Lyons had been imprisoned for 2 months by that stage.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t the end of his misery. He was eventually released in 1799, having languished unnecessarily behind bars. The affair was an embarrassment for the higher-ups, and they didn’t want to admit their terrible mistake. Instead, they tried to cast Lyons as an accomplice.

Meanwhile, Davis kept his freedom, with merely a legal slap on the wrist. h2g2 speculates, “Perhaps because he was the son of a judge, he was only required to repay the stolen money and was removed from the Carpenters’ Company list.”

Lyons wrote a pamphlet about his ordeal, though readers may have been dissuaded from his plight by the elaborate title: “Narrative of Patrick Lyon Who Suffered Three Months Severe Imprisonment in Philadelphia Gaol on Merely a Vague Suspicion of Being Concerned in a Robbery of the Bank of Pennsylvania With his Remarks Thereon.”

In 1805, after a period of hardship and his good name in the mud, Lyons rallied against his prosecutors in a landmark civil case. The Carpenters’ Hall website mentions that “The jury deliberated four hours and returned with a whopping $12,000 verdict in favor of Lyon. The defendants appealed and were granted a new trial set to begin in March 1807. Just as the second trial was to start, an agreement was reached awarding Lyon $9,000.”

Lyons became symbolic of an individual who’d beaten the system. A portrait was commissioned from artist John Neagle in 1826, though this had a simpler title than the subject’s pamphlet: Pat Lyon at the Forge.

As described by h2g2 it “was often reproduced in media of the time. Lyon became a symbol of the ingenious craftsman. He went through persecution because he was a recent immigrant. Restored in fortune, he became affiliated with the same people who had oppressed him.”

In attempting to secure justice, an innocent man had been subjected to the very worst the concept had to offer. He was now financially secure, though perhaps chose to keep his funds in a vault other than that of the Bank of Philadelphia.

Steve Palace is a writer, journalist and comedian from the UK. Sites he contributes to include The Vintage News, Art Knews Magazine and The Hollywood News. His short fiction has been published as part of the Iris Wildthyme range from Obverse Books.