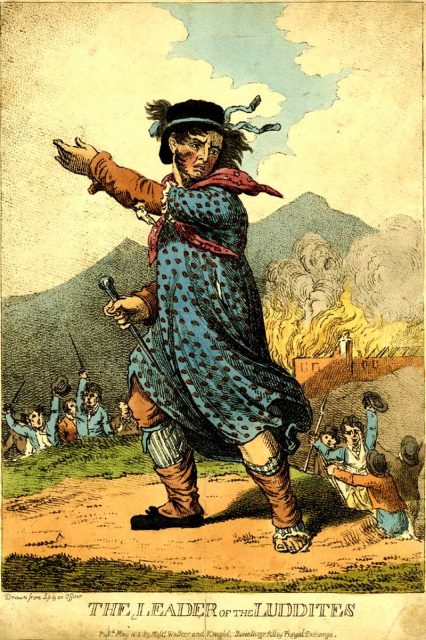

It is most likely that Ned Ludd was a mythical figure, but even so, the folklore story of “General Ludd” who lived in Sherwood Forest might have inspired one of the most passionate and disruptive uprisings in 19th century Britain.

Ned Ludd’s story first appeared in The Nottingham Review on December 20, 1811. In the story, Ned Ludd is described as a weaver from Anstey (near Leicester, England).

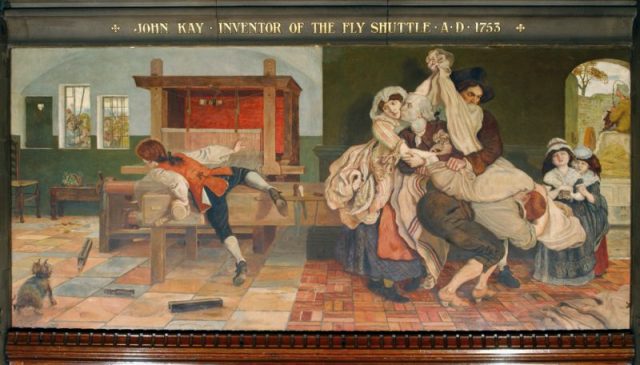

In 1779, after being beaten for not working hard enough, some accounts say he was taunted by local children, Ludd flew into a “fit of passion,” and smashed two knitting frames.

While this story is mostly fictional, it has since then been cited as the inspiration for what soon followed: The Luddite movement.

The movement began on March 11, 1811, in Arnold, Nottingham. At first, the “Luddites” were a small band of passionate, disenchanted weavers, textile workers, and other laborers. They were frustrated and enraged at the thought of being replaced by industrial machines.

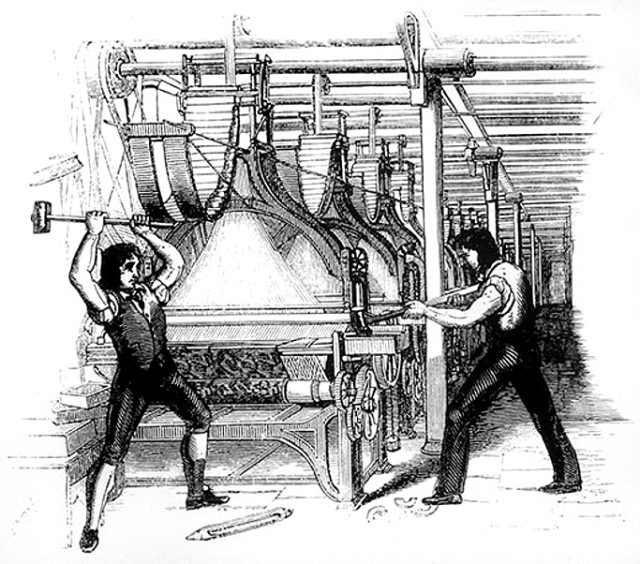

They would meet in small numbers on the moors of Nottinghamshire. There, they practiced destroying industrial machinery by the light of the pale moon. Then they would don masks and sneak into the towns and cities to carry out their attacks.

It only took two years for the movement to pick up speed and sweep across England, with Luddite groups cropping up in West Riding of Yorkshire in 1813.

Luddite handloom weavers burned mills. They sabotaged and wrecked factory machinery. The Luddite textile workers destroyed industrial equipment and even began attacking those who owned and operated them.

Once such incident was carried out by a small band of Luddites led by George Mellor. They planned to ambush and assassinate William Horsfall, a wool and textile manufacturer from Ottiwells Mill in Marsden, West Yorkshire, at Crosland Moor in Huddersfield. Horsfall owned a textile factory and was an outspoken critic of the Luddite movement.

George Mellor and his group ambushed Horsfall at night near Crosland Moor. After Horsfall made a scornful remark to his attackers, Mellor shot him in the groin. Horsfall died of the wound, and Mellor and his fellow Luddites were arrested.

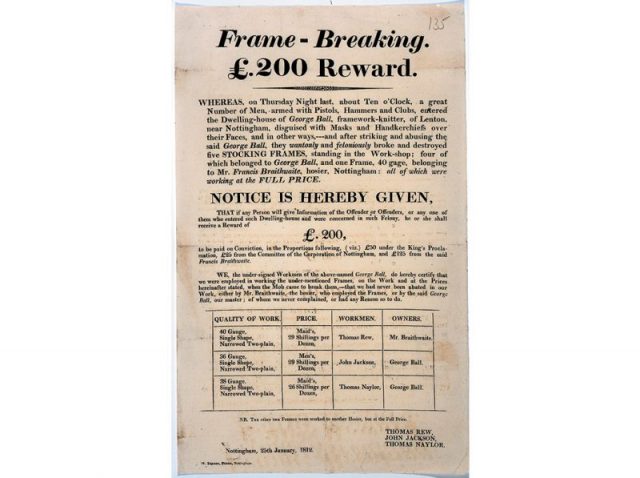

British Parliament had already passed legislation to combat what they called Industrial Sabotage. In 1721, they had criminalized the act of “Machine Breaking,” and they had passed the Protection of Stocking Frames Act in 1788.

18 Old English insults we need to bring back

Clearly, the Luddite movement proved that the penalties for these crimes weren’t severe enough. To solve this problem, Parliament had passed the Frame Breaking Act of 1812, which made machine-breaking a capital offense punishable by hanging.

So in 1813, when the British Government arrested George Mellor, they brought 60 other Luddites to a trial in York where they were charged with various crimes in an attempt to squash the uprising.

However, many of those who were charged were only self-proclaimed Luddites and not connected to the movement. Because of this, 30 of them were acquitted due to a lack of evidence. The Luddite movement lost a lot of momentum after this trial.

In 1817, Jeremiah Brandreth led the Pentrich Rising, where a few hundred stockingers, quarrymen, and ironworkers carried out what is now considered the last action of the Luddite movement.

In 1861, Parliament continued to crack down on acts of Machine sabotage by passing the Malicious Damage Act.

Read another story from us: What Caused the Great Irish Potato Famine of 1844-1849?

While the Luddite movement might sound like a minor conflict, the British Army once deployed more soldiers in the fight against the Luddites than they had in their fight against Napoleon Bonaparte.