One of the great warriors on TV right now is Lagertha on “Vikings.” The real Lagertha, if she existed, was Ragnar Lothbroks’ second wife, not his first, and that’s all we know of her.

Let’s take a look at five female warriors from history that were real.

Artemisia

Fans of the “300” movies about Greece will know of Xerxes, the great Persian emperor who tried to invade Greece and the West.

In the second installment of the series, Eva Green plays Artemisia, a cruel and beautiful sea queen allied with the Persians.

Artemisia really existed – but she did not command legions of ships, some of them iron-clad.

However, she did sit on the throne of a minor Greek kingdom in modern-day Turkey and commanded a small fleet of five ships.

She won some small victories at sea and was respected by Xerxes, who asked her opinion about whether he should fight the Athenians at Salamis.

Artemisia advised against it, telling the emperor that he was likely to lose and to wait for a more auspicious time.

Xerxes ignored her advice and ordered his fleet, including her ships, to attack.

Artemisia’s ships sunk a number of Athenian vessels. She also used trickery to get herself out of a tight spot by carrying Athenian pennants aboard her ship.

When in danger, or on the attack against an isolated Greek ship, she raised the flag to fool her enemies. She and most of her small fleet survived the battle. Afterwards, Xerxes asked her advice again – should he stay in Greece and lead an invasion? She told him to go home. He could leave a general – if the general won, Xerxes could claim credit, if he lost, the blame. This time Xerxes listened.

Artemisia’s kingdom enjoyed privileged status in the Persian Empire and thrived.

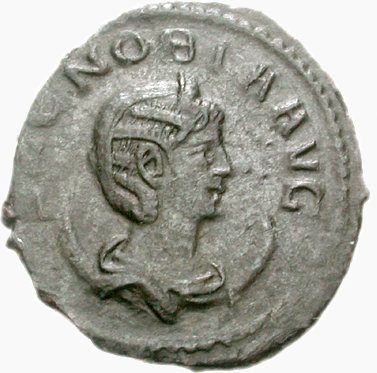

Zenobia

Zenobia was Queen of Syria in the 260s and 270s AD. On the outskirts of the Roman Empire and yet part of it, Zenobia chafed at rule from afar, and especially taxation. She also thought that Rome could do more to protect her from the Persian Empire to the east.

In the late 260s Zenobia fought a series of battles against the Persians and won. This gave her confidence to challenge Rome itself. Forcing a number of Roman governors and generals to join her army, she led a force of Syrians, Arabs, Armenians and others on a campaign that saw her conquer Syria, the Levant, much of present-day Turkey, and Egypt.

When she began the rebellion, Rome was ruled by Claudius Gothicus, a weak ruler who was busy putting down a revolt in the Balkans that was a more direct threat than Zenobia. By 270, he was replaced by Aurelian, one of the great later Roman emperors.

At first, both Romans were willing to put up with Zenobia. They had other matters to attend to and Zenobia herself claimed she was ruling in the name of Rome, as a “protector of the east.” Food and taxes still flowed into Rome itself. However, by 272, Zenobia had begun calling herself “Empress of Rome.” That was taking things a bit too far.

Aurelian chased her all the way back to Syria, though she and her generals put up a good fight. In the end, however, her rebellion failed. History is unclear about what her fate was. Some believe she died on the way back to Rome in chains. Others have her beheaded in a Roman triumph. Others still believe she was held in house arrest in Rome, married a Roman noble and had Roman children.

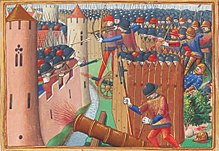

Joan of Arc

Joan was 17 when she had what she believed was a religious vision. God had told her to go to King Charles VII of France and offer herself to him as the leader of his army.

Joan’s charisma and belief were so great that the king actually put her in charge of his army. A teenage girl. In the 1400s. In charge of an army. Unbelievable, yet it happened.

In her greatest victory, Joan led the forces of the French king against the English and lifted their siege of Orleans.

To this day, Joan is also known as the “Maid of Orleans.” She also led French forces in other lesser known victories.

Joan was charismatic and her troops believed that they, through her, were also God’s instruments to rid France of its enemies.

Charles VII’s enemies — the English and their allies, the rival French house of Burgundy — saw Joan as the greatest danger to their plans.

The English wanted security for the lands they had held in France for two centuries, and the Burgundians wanted the throne.

On April 23, 1431, Joan was captured as part of the rear guard of a French force attempting to retreat to safety against greater Burgundian numbers.

She was put on trial for heresy by English and Burgundian clerics and burned at the stake one week later. She was canonized by Pope Benedict XV in 1920. Joan of Arc is one of the nine patron saints of France.

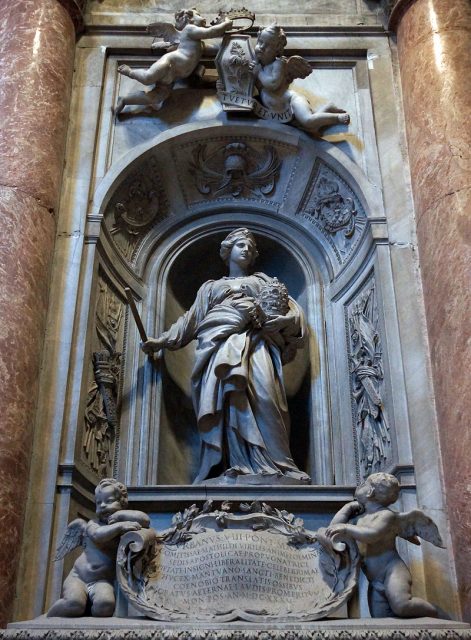

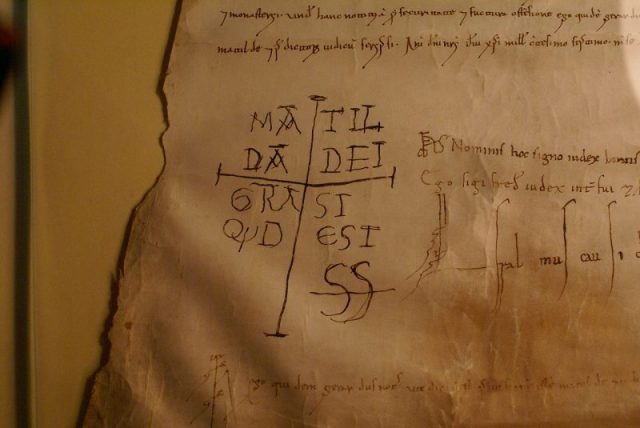

Matilda of Tuscany

In 1076, Matilda inherited Lombardy, Tuscany, and Emilia-Romagna in northern Italy. She was the ruler of the three most powerful Italian states at the time.

At the same time, the Holy Roman Emperor (and King of the Germans) Henry IV and the Pope, Gregory VII were at war with each other and their allies over the rights to appoint church officials in their lands. Matilda supported the Pope.

This resulted in Matilda’s lands being invaded a number of times, and each time, she won.

Others had not been so lucky, but by a combination of skill, leadership, marriage with a strong ally, and geography, Matilda was able to keep Henry at bay when others could not.

Matilda’s victories caused other Italian city-states to align with her and revolt against Henry as well.

Unfortunately, this could not last. Henry IV’s successor, Henry V, was too powerful and threatened the wholesale destruction of northern Italy.

Wisely, Matilda chose to compromise and became “Imperial Vicar and Vice-Queen of Italy.”

In this position, she helped foster an understanding between the Pope and the Emperor and turned to her energies away from war. Before her death, she is said to have founded more than 100 churches.

Grace O’Malley

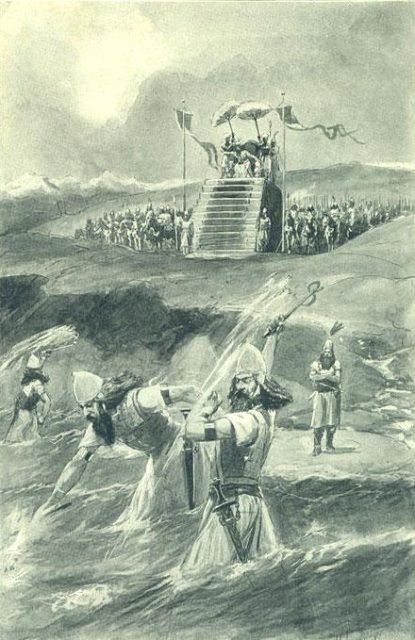

Grace lived during the reign of Elizabeth I of England. She was born around 1530 and died circa 1603.

She became the ancestral ruler of the O’Maille Dynasty of western Ireland following the death of her father Eoghan.

This despite having a brother, who should have inherited the title. However, Grace was much smarter and cleverer than her sibling and her countrymen recognized her talent.

During her rule as head of her house, Grace supported a rebellion against the most prominent Irish families, who were seen as siding with the English in their quest for power. The late 1500s were a time of ever increasing English control of Ireland. Grace commanded both forces on land and at sea, practicing a type of guerrilla warfare and piracy at sea.

In 1593, she and members of her entourage were taken prisoner by the English. Grace was brought before Elizabeth I, and by all accounts, gave the Queen a talking to about the abuses of the leading Irish families, as well as their double-dealing. She also gave the English queen a lesson in etiquette.

The entire conversation took place in Latin, which surprised the English ruler, who had thought the Irish unsophisticated.

Read another story from us: George Washington’s Bizarre False Teeth

The result of this conversation was a compromise on both sides. Elizabeth would remove the present English governor, who was accused of abuses, and Grace would end her raids. She died at the age of 73 after a long reign as her tribal chief.