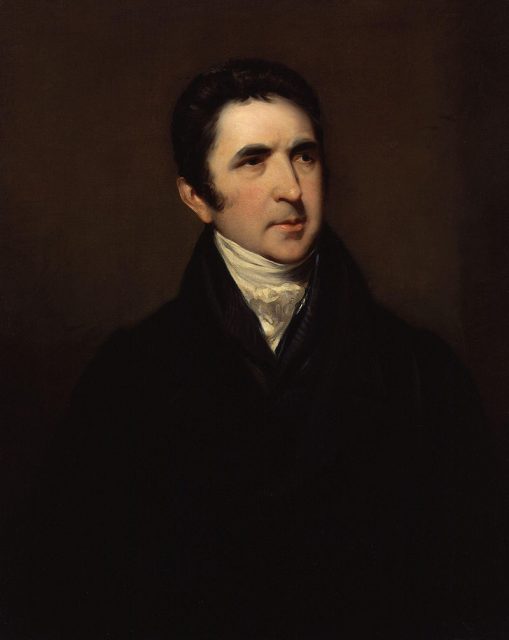

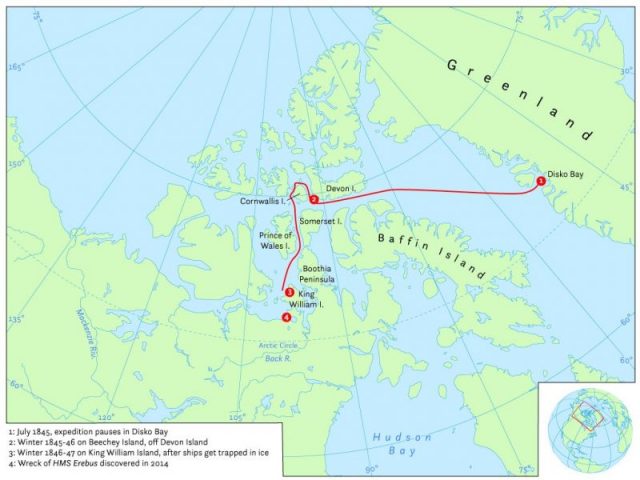

In 1845, British Rear Admiral Sir John Franklin, after much petitioning for the job, was tasked with finding the Northwest Passage leading to China and India between northeastern Canada, southern Greenland, and the most southern point of the Arctic.

At the time it was believed that there was a waterway in Northern Canada that went from east to west allowing ships to take a shortcut to the Pacific Ocean without having to sail around the tip of South America.

While the Pacific can be reached from the East, the routes are above the Arctic Circle, mostly frozen, convoluted, and peppered with islands.

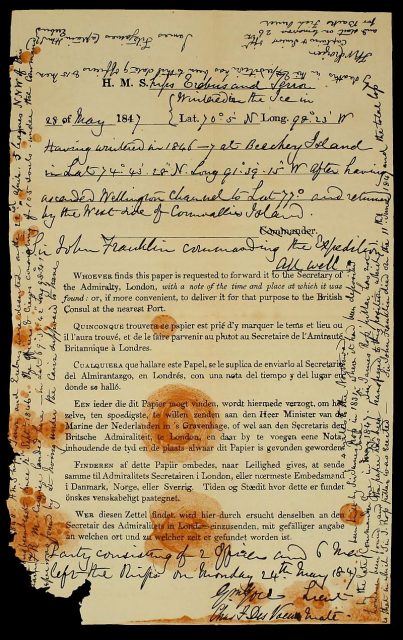

With two ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, he and over 130 sailors set out on their adventure.

Upon reaching North America and the Arctic their ships became locked into the ice, and within three years they had disappeared, never to be heard from again.

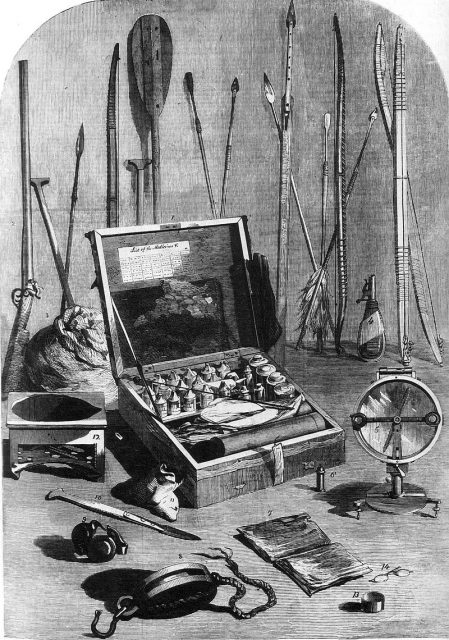

While artifacts and objects were found for years by explorers and the native Inuit people, it took over 160 years to find the ships.

Franklin was an experienced Arctic explorer, having been on four previous missions. On one of the missions in 1819, he ate shoe leather to stay alive, which so impressed the public that he was considered a hero back in England.

According to Mental Floss, the preparation for the journey included strengthening the bow of the ship to cut through the ice. The ship’s provisions included around 5,000 gallons of ale, 32,000 pounds of salt beef, 36,000 pounds of hardtack, almost 4,000 gallons of concentrated spirits, 20,000 cans of soup, and 8,000 pounds of canned vegetables.

The ships also carried a well stocked library, naval instruments, and the newly invented daguerreotype camera.

The English Admiralty was not particularly concerned when the ship initially disappeared because of the large stores of food and drink, but, unbeknownst to them, most of the food had gone bad because of a faulty canning procedure.

It wasn’t until Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin, started putting pressure on the Admiralty that they began to search for the explorers.

Lady Jane had written thousands of letters to gain support for a rescue mission.

She contacted politicians, clairvoyants, writers such as Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain), and the President of the United States, Zachary Taylor — a very bold move as most official intercontinental mail was required to go through specific channels.

She used her own funds to finance additional rescue missions and offered a substantial reward to anyone who could either find the crew or supply information that would lead to their discovery.

Samuel Clemens immediately assumed the explorers were attacked and killed by the Inuit, which couldn’t have been further from the truth.

In fact, the fate of the explorers could have been learned much earlier if the Europeans had listened to the Inuit. For years they had shown the Europeans artifacts such as Franklin’s personal flatware, combs, buttons, and parts of the ships.

They informed the men about graves of three of the men from the expedition, and they knew exactly where one of the ships had sunk, but the Europeans dismissed their claims.

When Hudson Bay Company surveyor John Rae met with Inuit to trade at Repulse Bay in 1854, he was told that about 30 corpses and additional graves had been found nearby as well as a few on a nearby island, and one appeared to be a “chief” as he had a gun and telescope.

The bodies were scattered: some in tents, some just laying around, and some under a boat that had been turned over for protection from the weather.

The Inuit told Rae where the bodies could be found, near Back’s Great Fish River. However, the British Navy and Samuel Clemens both dismissed Rae’s findings as “the babble of savages.”

With advice from an Inuit historian, the HMS Erebus was found in Victoria Strait in 2014 using sonar, and the HMS Terror was discovered in 2016 after an Inuit hunter reported seeing it in Terror Bay, near King William Island.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HHeFc_yVgLE

The three bodies found buried on Beechey Island were exhumed and tested. Very high levels of lead were found, indicating the faulty seals on the canned food may have leached into the food and poisoned the men.

In addition, the men suffered from scurvy, tuberculosis, overexposure to the freezing weather, and starvation. High levels of lead can also lead to insanity which can be fatal in such an unforgiving climate.

Read another story from us: Unbelievable Endurance – The Crew that Survived an Antarctic Shipwreck

Most of the artifacts that were found are now housed at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London. There is also a traveling exhibition of artifacts including the bells brought up from the ships.