Recently, Professor Andreas Hennius of Uppsala University in Sweden published a paper which indicates that the production of pitch increased many-fold just at the time when the Scandinavians were beginning their expansion in the early Middle Ages.

Pitch was a crucial ingredient in the crafting of wooden sea-going vessels. It coated the wood, and along with other various elements, such as straw and/or leather, was used to fill the cracks and seams that came with ship production. Without pitch, the long voyages of the Vikings would have been impossible.

Not only did the Vikings perfect almost completely water-proof pitch, but they made it on an industrial scale.

In recent times, historians, economists, and archaeologists have been putting together a picture of an incredibly advanced culture – radically different from the image of the uncivilized savages that were held before the latter part of the last century.

In the time before the Viking Age, known as the “Scandinavian Bronze Age,” the Northmen began to develop sleek vessels for crossing the North and Baltic Seas to raid the coast of close territories.

These were smaller vessels, and we know what they look like because those who sailed in them left stone carvings throughout the North and Baltic Seas’ coasts. Between 100 AD and 600 AD the pitch was made in small pits, each capable of producing enough for a small local fleet.

In the 700s, the Vikings began to sail their famous long-ships. They probably sailed in small groups, representing their local chieftain. They banded together for safety, for though the Vikings had little to fear from the other cultures of the area, they did prey on each other — earls and warlords fighting each other for control and riches.

As territories became larger, the fleets and armies grew, as did the need for protecting what had been won. By the time the raids on England, France, and Russia began in earnest, those fleets sometimes contained hundreds of vessels. Viking influence was set so deep in the British Isles that many Viking words are still used in the English language today. Check out the video on this topic:

https://youtu.be/TchiY6MSjm8

Think of what it took to build and coordinate this type of invasion. Timing, sourcing, means of production, skilled and unskilled workers (slaves) – sometimes in areas hundreds of miles apart, all had to be coordinated with each other.

One thing Scandinavia had in absolute abundance is wood. Wood on a monumental scale had to be found, cut down, transported, crafted and put together. Cloth sails: linen and other cloth had to be either imported or produced, then made.

For example, the size of the Great Heathen Army which invaded England in 865 AD is estimated at anywhere between six and fifteen thousand (Viking historians are still hotly debating the question). The largest of the Viking long-ships carried somewhere between sixty and eighty men. Assuming a force of ten thousand men, and an average of sixty-five men per ship means a fleet of over 150 ships. A much larger capacity than most ships at the time.

This does not include the possible use of the “knar,” the Viking version of the cargo ship. The production of this fleet must have involved a majority of the population. It’s possible food producers and blacksmiths were also Vikings, but either way, tens of thousands of people supported the fleets and their construction. And then there’s Professor Hennius’ discovery of pitch production.

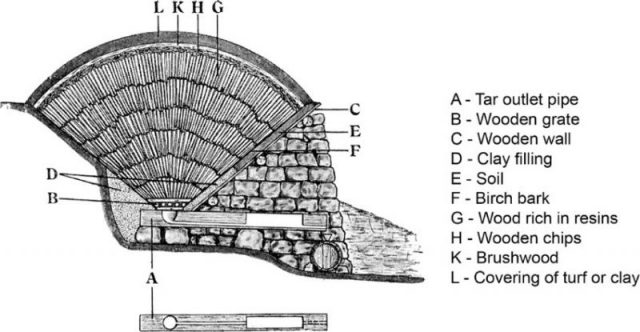

Professor Hennius and his colleagues found remnants of tar pits big enough to make 300 liters of pitch at a time. Again much more efficient than most other ships at the time.

They dated the larger pits they found to the years between 680 and 900 AD, the period of the great Viking raids. Initially, the pitch pits were close by the Viking settlements on the coast, but as more of the pinewood needed to make pitch/resin were cut down, the production moved farther and farther away from settled areas.

Read another story from us: The Key Role Vikings Played in the History of Ireland

This would have added another wrinkle in the Northmen’s pitch production – wood had to found and pitch made – both needed to be transferred to the coast.