With a vast expanse of uncharted wilderness deadly to the unawares, Australia in the 1800s was a paradise for roving outlaws called bushrangers.

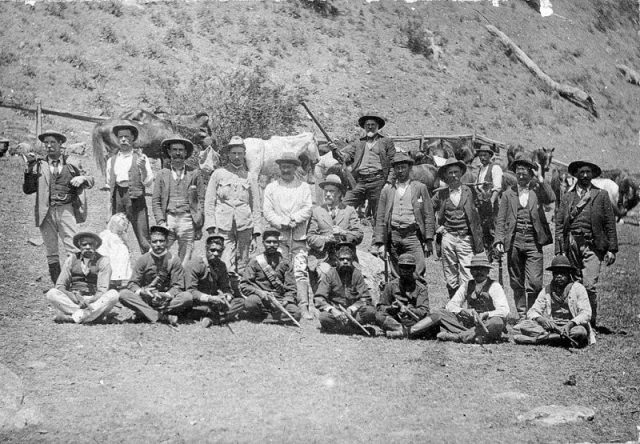

These men — half Wild West gunslingers and half Robin Hood-like folk heroes — captured popular imagination by defying the harsh colonial regime, holding up banks or cross-country stage coaches.

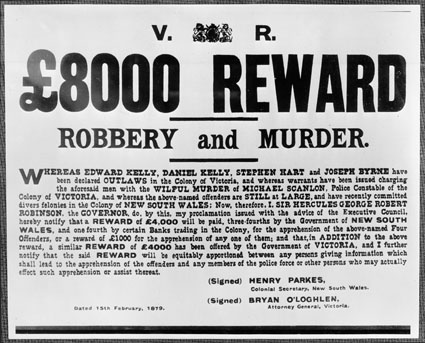

Edward “Ned” Kelly is the best known of their number, appearing in countless film adaptations, folk songs, books and poetry. But by the time the Kelly Gang rode out of the scrub and into legend in 1878, the era of the bushranger was at an end.

Between 1788 when New South Wales became a penal colony for Great Britain’s convicted criminals and 1880 when the Kelly Gang were executed, an estimated 2,000 bushrangers were reported to have been at large.

With a population of convicts vastly out-numbering their jailers, who relied upon the unforgiving landscape instead of chains and bars, heading off grid and resuming a life of crime was inevitable.

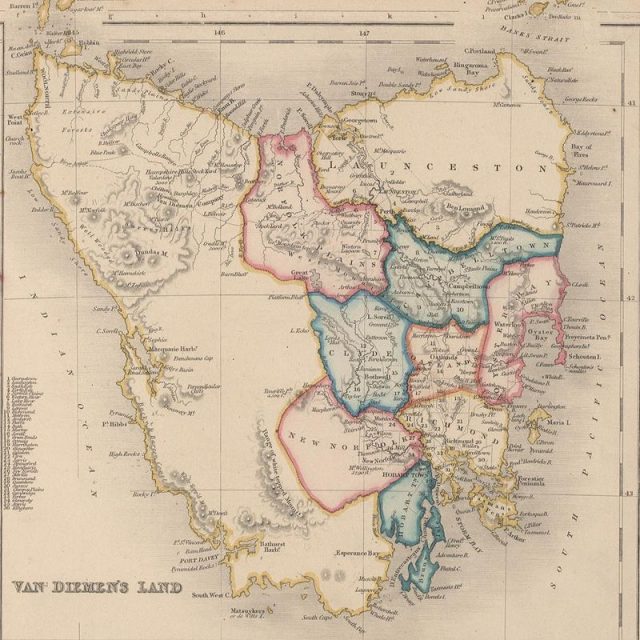

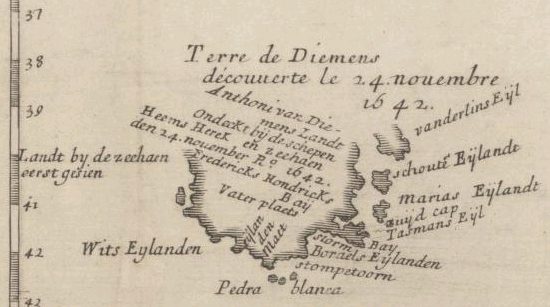

Nowhere was this more prevalent than the island of Tasmania, then known as Van Diemen’s Land, which was settled as a penal colony in 1803.

Van Diemen’s Land was the final destination for the most hardened convicts from Great Britain and Ireland, and for those convicts who had re-offended since being shipped to New South Wales. In short, it was the prison’s prison and they were the worst of the worst.

Situated off Australia’s southern coast, Van Diemen’s Land was mountainous, green and forested with little of the vast expanses of the mainland. These highlands were the ideal environment for bushrangers to hide — and to become organised.

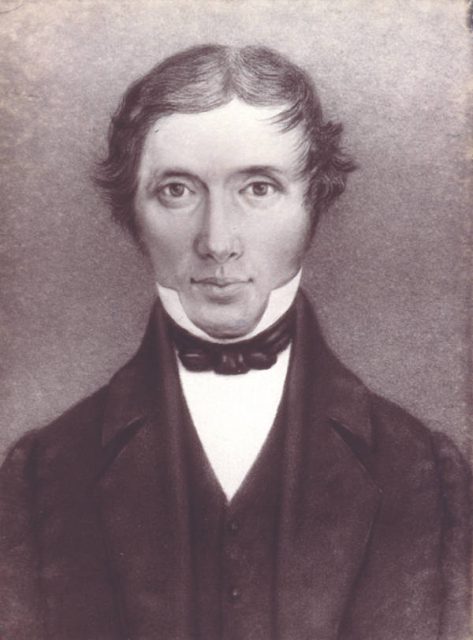

A former soldier from Yorkshire in England, Michael Howe had robbed a man on the road. Arrested and sentenced, he arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in October 1812. Rather than work off his guilt, he declared “that having served the King, he would be no man’s slave” and absconded to join other runaways in the bush.

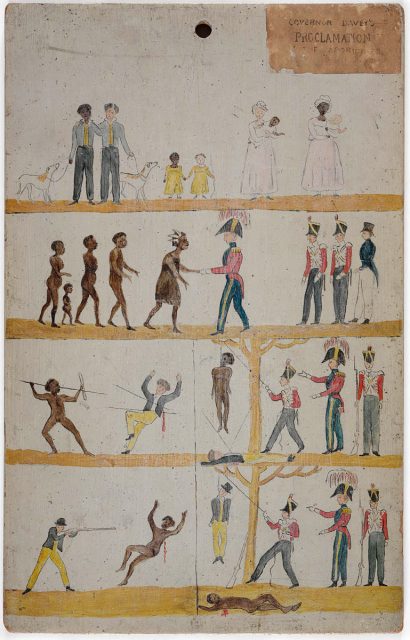

By 1813, Van Diemen’s Land was an island in rebellion. Lieutenant Governor Thomas Davey, who officially ran the island and answered to Governor Lachlan Macquarie in Sydney, was fighting a losing battle against the epidemic of bushranging.

Desperate to clean up the island where his deputy had failed, Macquarie offered an amnesty for any crime short of murder to any outlaw who turned himself in. Howe took advantage of the amnesty but soon returned to his life as an outlaw, joining a gang led by John Whitehead.

With a time limit on the amnesty, many bushrangers waited until the offer was just about to expire — going on an energetic spree of robbery and then having themselves pardoned at the last minute, so they could start their criminal careers all over again. Howe was most likely one of their number, simply abusing the system with no real intention of going legit.

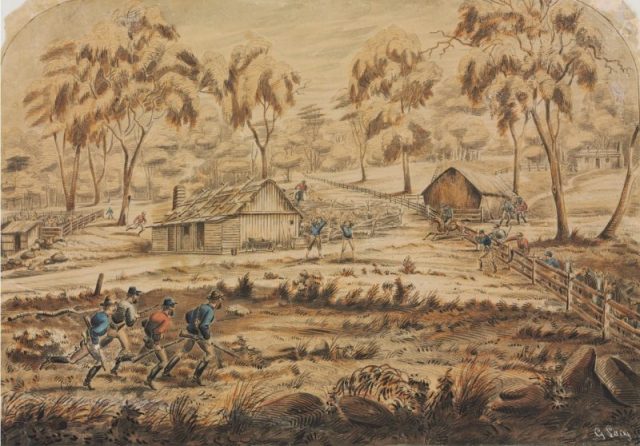

The Whitehead Gang robbed houses and burned crops, killing two settlers who attempted to bring them in and wounding others. With a hefty reward offered for bringing them in, Whitehead — wounded in a firefight with the lieutenant governor’s men — ordered Howe to cut his head off so that nobody could claim the bounty. Howe obliged, killing his boss and hacking his head from his shoulders.

Now the leader, Howe embarked on a rampage so extreme that Davey declared martial law. This was the governor’s prerogative, not the lieutenant governor’s and he ignored Macquarie’s orders to stand down. This had become personal and Davey even led a military expedition against the bushrangers himself.

He also tried to cut off their access to currency. In order to sustain the fragile settlement’s economy and keep them fed, the government stores purchased goods from farmers and then sold them on to the population.

Davey banned the trade of kangaroo skins and prevented the government stores from purchasing kangaroo meat, which often came from the bushrangers.

Instead, men like Howe began to raid domestic livestock — sheep and cattle — and sold them through “honest” farmers directly to the government.

Howe began to write letters to Davey, and then his successor William Sorrell, directly threatening to set the island aflame. The outlaw leader called himself “Governor of the Rangers” and “Lieutenant Governor of the Woods,” and referred to Davey and Sorrell as “Lieutenant Governor of the Town” — a sign that as far as the bushrangers were concerned his authority ended at Hobart’s limits.

This was more than just megalomania; Howe ran a protection racket over the entire countryside. It’s claimed that he forced the wealthy elite to strike deals with him in order to work the land or move produce between their farms and the town. The records of which landlords profited and which rapidly declined, and whose country houses were raided by the bushrangers and whose weren’t, tell a tale of collusion and corruption.

Howe was reported to have 100 men in his gang, all of whom he required to swear an oath of allegiance, and by 1815 all bushrangers in Van Diemen’s Land took his lead. Those who stood against him were ruined — the chief constable had his sheep stolen 50 and 100 at a time, and his corn set alight at the dead of night. His house was robbed of all its valuables.

Critical to their success in the bush, Howe allied himself with Aboriginal communities. He meted out corporal punishment to any of his band who harmed an indigenous person and his gang was noted to have Aboriginal members — include his own lover, known predictably to the British as “Black Mary.”

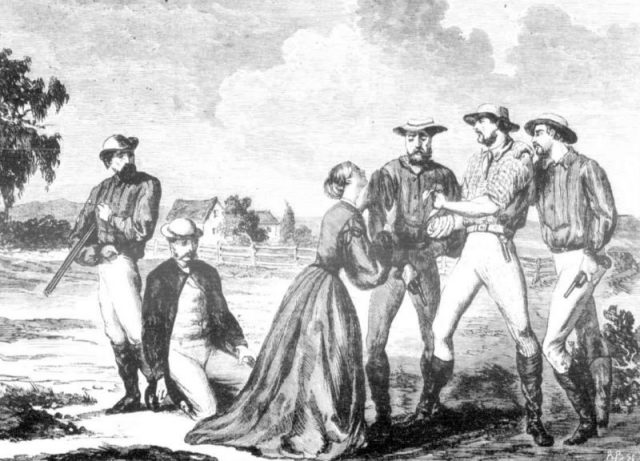

This alliance was to be Howe’s downfall. Fearing she was about to be captured in a government ambush in 1817, Howe tried to shoot Mary rather than risk her talking to the authorities. She survived, and feeling betrayed, Mary led them to Howe’s hideout and forced the once-mighty “Governor of the Rangers” to go on the run.

Howe was on the back foot and negotiated with Sorrell to turn himself in and sell out his collaborators in exchange for a pardon and permission to leave the island. The lieutenant governor agreed and Howe sheepishly surrendered himself at Hobart.

No records exist of the investigation or confessions that followed, but with so many of Hobart’s society in cahoots with the outlaw king “a complete exposure of all the bushrangers [and] interconnecting linkages would shake Van Diemen’s Land to its very rum-cellars.” Historians have argued that had there been any serious intention to expose Howe’s criminal conspiracy, he would have been shipped to Sydney and interrogated there, but influential people made certain he stayed where they could keep an eye on him.

In 1818 some sort of agreement was struck between Sorrell, Howe and Howe’s powerful friends, and he returned to the bush. With no pardon forthcoming and his empire in tatters, his one-time collaborators resolved to have Howe killed. He was no longer in a position to seriously damage their profits as he had been when he commanded an army of a hundred, and if he was captured again he risked exposing them.

“Black Mary” was dispatched to Sydney to prevent the two reconnecting and Howe renewing his Aboriginal alliances, and a reward was offered for his death or capture that caught the eye of every convict in Van Diemen’s land — 200 guineas in cash, a pardon and free passage to England.

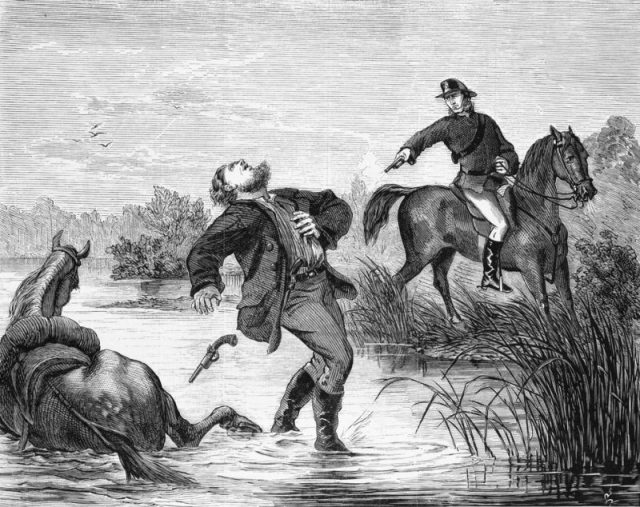

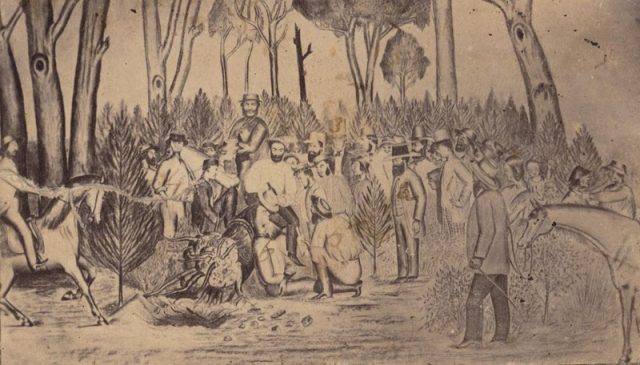

In September 1818, Howe was lured to a meeting with a convict stock-keeper called Thomas Worrell to sell him some kangaroo skins. Worrell waited by a hut near the Shannon River, while Private William Pugh of the 48th Regiment hid inside with his rifle, peering anxiously out for sight of the notorious outlaw.

Weather-beaten, worse for wear, and clad in a patchwork of kangaroo skin, Howe attempted to shoot himself free as Pugh “ran up, and with the butt end of his firelock [rifle]… battered his brains out.”

Howe’s head was displayed in Hobart for all to see, while his body was left were it fell.

In the dead outlaw’s knapsack was found a kangaroo-skin journal in which he had written his dreams in kangaroo blood — nightmares of ambush and betrayal by Aboriginals, soldiers and even his own sister — and lists of all the seeds he intended to plant in his wild green kingdom.

Read another story from us: The Bearded Legend of Ned Kelly – Australia’s Robin Hood

The king was dead, but he was not forgotten. A folk hero to the convicts (even if they had eyed up that reward enviously), those who turned against Howe were ostracised and the “Lieutenant Governor of the Woods” became a legend.