Born in 1797, what connection could an author have with the second world war? His premonition of the horrors to befall 20th century Europe are eerie to say the least.

Heinrich Heine, the author in question, was born to a Jewish family in a time when antisemitic sentiments were rife among the yet-to-be unified German kingdoms.

Next door, the French government chose to ignore the Damascus Affair in 1840 because it didn’t want to aggravate the Catholics nor the push forward for colonization of the Middle East, permitting antisemitism to continue to grow in Europe.

Though interested in the faith on a historical level, Heine was never a particularly devout Jew. He converted to Protestantism in 1825 in order to circumvent a Prussian law that prevented Jews from occupying academic posts.

Essayist, poet, and critic, Heine was popular during his lifetime in spite of (or perhaps because of) his penchant for revolutionary ideals. Though fiercely nationalistic, Heine supported liberty and equality unknown in the conservative, monarchical Germany of the time.

Censorship of the time had a funny rule that books under 320 pages were to be reviewed before publication. Anything larger was considered to be uninteresting to the general public and not worth the censors’ time.

Heine’s publisher flouted this law by printing his clients’ work in large font, increasing the page count and bypassing the censors, but still spreading revolutionary texts. 1834 saw an end to this loophole, and as Heine refused to be censored, his work went unpublished in Germany. He had settled in France where he would remain for the rest of his life.

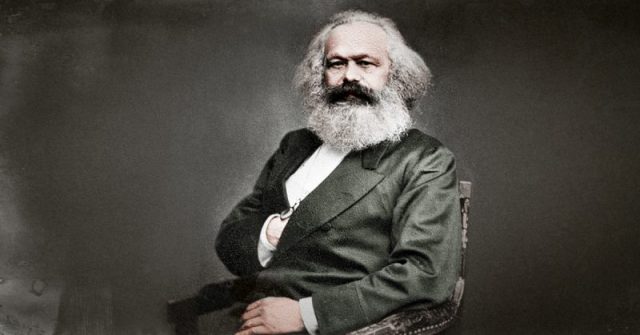

A relative of Karl Marx, Heine would influence the writings and development of the political theories made famous by his cousin. As both were exiled in Paris, they published writings together until Marx was deported, after which their close relationship began to fade as time went on and Heine developed a distaste for Marx’s communist ideals.

Plagued by criticism and censorship, Heine didn’t make life any easier for himself. He regularly involved himself in liberal factions at the universities he attended, held questionable and unrequited romances, and challenged 10 different people to duels throughout the years.

Though regarded as a literary celebrity, his exile in Paris was also fraught with dissidence within the Young Germany group, exacerbated once again by Heine’s tendency towards provocation, culminating in his last duel in 1840, which he survived.

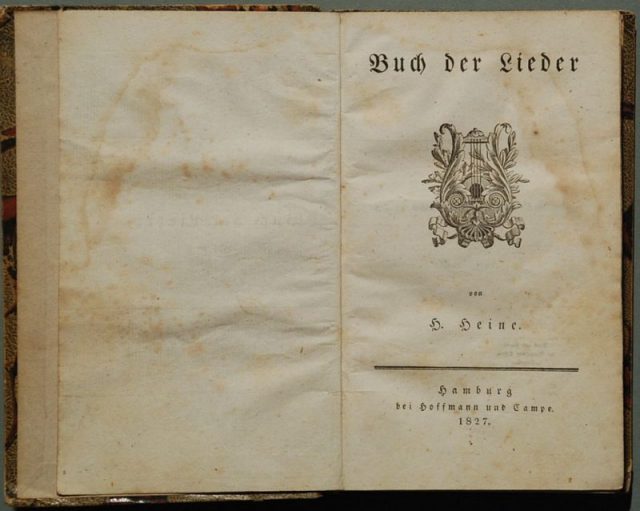

Despite his uneven popularity, Heine is credited with writing the most widely known book of German verse, Buch der Lieder, in 1827.

He is credited with an impressively long list of publications, all of which were written in German, and many of which were set to music by admirers such as Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Schubert, and Wagner — just to name a few.

Banned by the German authorities during his own lifetime, Heine’s works faced backlash again when they were posthumously banned by the Nazis in the 1930s. Censorship went beyond bans and up in flames, when in 1933 Nazi students and youth began a nationwide book burning in Berlin.

The first works attacked were those of Marx. His cousin’s would soon follow suit. Never mind an author’s actual political leanings or literary message, under the Nazi regime, Jewish authors were all censored, “regardless of subject matter.”

Ominously, a character in Heine’s play Almansor (1821) declares “That was but a prelude; where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

One can’t help but wonder whether or not the Nazi censors were aware of the terribly ironic scene they enacted in Opernplatz that repressive evening, or if anyone could have guessed at the tragedy to come.