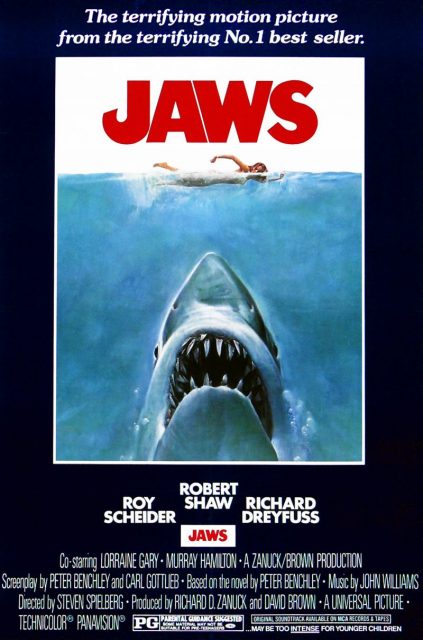

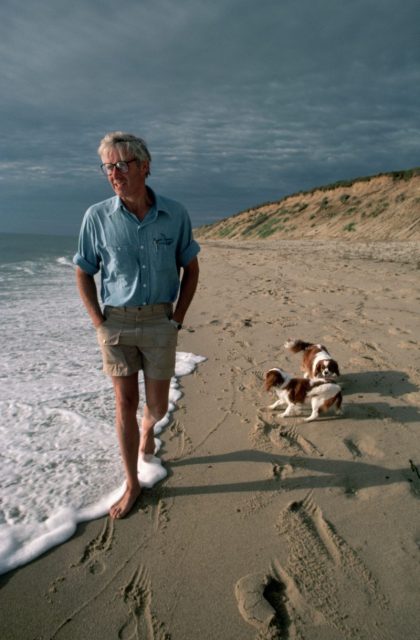

Peter Benchley was a relatively young author when his first novel was published in 1974. And unlike many debut novelists, he had a smash hit on his hands. The book was Jaws and it made Benchley’s name before he’d reached middle age.

As a journalist and White House speechwriter he was used to warning about big beasts of the political scene. His infamous tale of a beachside community being attacked by an enormous great white shark took him out of the corridors of power and into the imaginations of readers worldwide.

Yet for Benchley the experience was a double-edged sword. Young genius Steven Spielberg made Hollywood’s first blockbuster out of the 278 page source material, putting the writer on the map a year later. As time went on however, he realized he’d done ocean life a disservice.

Quoted in a 2014 Smithsonian article, he remarked “I see the sea today from a new perspective, not as an antagonist but as an ally, rife less with menace than with mystery and wonder.”

In both book and movie form, Jaws had awakened a primal fear in audiences. Few who saw it looked at the water the same way again. Swimming for pleasure went out the window for fear of being devoured by an ancient and relentless predator. As oceanographer Matt Hooper (played by Richard Dreyfuss) explains in the film, “What we are dealing with here is a perfect engine, an eating machine.”

The resulting backlash against sharks led to genuine experts questioning the story’s visceral power. “The key problem Jaws created,” a 2015 BBC piece writes, was to portray sharks as vengeful creatures.”

Combine what appeared to be a dead-eyed monster with a hunger for vengeance and it was easier for Mankind to objectify them as a species. While sharks were especially likely to wind up in a bowl of shark fin soup, there was also a sense of “seek and destroy” in some people’s minds.

Away from the pages of a best seller, the reality is somewhat different. The BBC notes, “some large shark species certainly do attack humans — about 10 people a year are killed, usually by great white, bull and tiger sharks. Rarely though are the victims actually eaten — often they die from trauma.”

There is also a long-established idea that sharks mistake the likes of surfers for seals, though this is disputed in some quarters who believe the predators are too sophisticated for that.

Related Video: The Incredible True Story Behind The Revenant

https://youtu.be/HfpOeVA87Ns

As recently as 2000 it was reckoned there was a 79 percent drop in the great white population, based on research conducted in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. Benchley the writer did his best to raise awareness of crimes against whites and other marine creatures over the decades, contributing to publications such as National Geographic.

Attitudes have improved and the outlook is better for the humble shark, but serious doubts still exist. Smithsonian writes, “Of the 476 species of sharks analyzed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature for extinction risk, good data are only available for 276, and of these 123 are considered at risk for extinction.”

Benchley passed away from pulmonary fibrosis in 2006. The Jaws franchise died out in the late 80s with the much-derided Jaws: The Revenge, focusing on a shark so vengeful it swam all the way to the Bahamas to avenge its predecessors. These days the author’s name is associated with inspirational initiatives like the annual Peter Benchley Ocean Awards.

It could also be argued that his vision of man vs shark was slightly misinterpreted. There were some rather eccentric takes of the story, some of which were even sexual in nature! But it’s significant to point out the conclusion of the novel, which deviates from the big screen version.

The Independent observed in 2014 that “Quint’s laconic rage while recalling his survival of the USS Indianapolis transforms Jaws into a revenge tragedy. Relentless, remorseless and even devious, the shark is a smiling villain, more Lee Van Cleef than Moby Dick. The Western subtext breaks the surface in the final showdown between great white and Sheriff Martin Brody.”

As moviegoers know, the shark is blown up after eating a scuba tank. Whereas on the page Jaws succumbs to exhaustion and expires. “This downbeat conclusion makes a more upscale argument than the film is capable of,” the article says.

“Benchley’s shark is an amoral force of nature: not bad, just hungry. And what amoral nature has unleashed, so amoral nature reclaims in death.”

Read another story from us: Jaws 2 was Nearly Set During World War II

The writer wanted to highlight humans and their projected rage as the true enemy. It was a conversation he would continue throughout his life, tackling the fishing industry and commercial interests rather than Great White sharks.

He said to the Guardian in 2000 that “We must not allow just one generation of humanity to needlessly eradicate 400m years of evolution.”