Government officials are warning of the return of “medieval diseases” in California, particularly after the news spread that a Los Angeles deputy city attorney said she had contracted typhus, a centuries-old horrific disease usually spread by rats, within L.A.’s City Hall.

After attorney Elizabeth Greenwood caught typhus, an illness that causes extremely high fever, muscle aches, and headache, she sued the city of Los Angeles for $5 million.

California Governor Gavin Newsom said in his State of the State speech in February 2019 that there was a public health crisis, citing outbreaks of hepatitis A in San Diego County and typhus in Los Angeles County. “Typhus,” he said in his address. “A medieval disease. In California. In 2019.”

From Jan. 1, 2018, through Feb. 1 of 2019, there were 167 cases of typhus in the state, up from 125 in 2013 and 13 in 2008, according to the California Public Health Department. Since the late 20th century, cases have been primarily reported in Africa, the Middle East, and South and Central America. Medical authorities say risk factors include visiting or living in areas where rats, mice, and other animals have high populations (such as disaster areas, refugee camps, and jails) and where fleas and lice can carry the bacteria from the animals to infect humans.

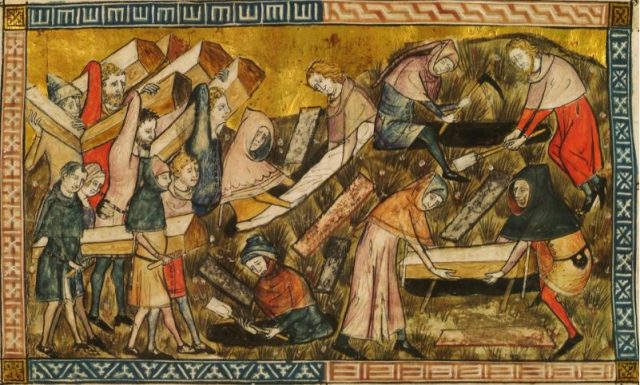

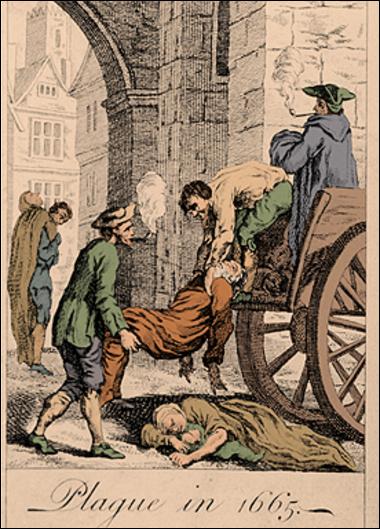

Typhus was first described in the late 15th century. It is estimated that 17,000 Spanish soldiers died of it during the siege of Granada in 1489. Since it was so prevalent in prisons, it was dubbed gaol or jail fever. In 1759, English authorities estimated about 25 percent of all prisoners in England died of gaol fever per year. In the 18th century, the disease was named typhus, from the Greek smoke or stupor because of the symptom of delirium.

A Brazilian doctor discovered the cause of epidemic typhus in 1916. Astonishingly, over 3 million fatalities were attributed to typhus during and after the first world war. Even though a typhus vaccine was developed before the next world war, typhus epidemics continued, especially in concentration camps (Anne Frank died in a camp from typhus). DDT was used to kill typhus-bearing lice at the end of the war; epidemics were rare after that.

Today typhus can be treated with antibiotics and the death rate is low. Why it is returning is the question. The outbreaks are more prevalent in overcrowded and trash-filled areas that attract rats. The disease has seen a reemergence in the homeless population of Los Angeles, officials say. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) said, “California accounted for 30 percent of all people experiencing homelessness as individuals in the United States and 49 percent of all unsheltered individuals” with a homeless rate of about 2.5 times the national rate, according to Forbes.

“The hygiene situation is just horrendous” for people living on the streets, said Dr. Glenn Lopez, a physician with St. John’s Well Child & Family Center, who treats homeless patients in Los Angeles County, in an interview with KHN. “It becomes just like a Third World environment.”