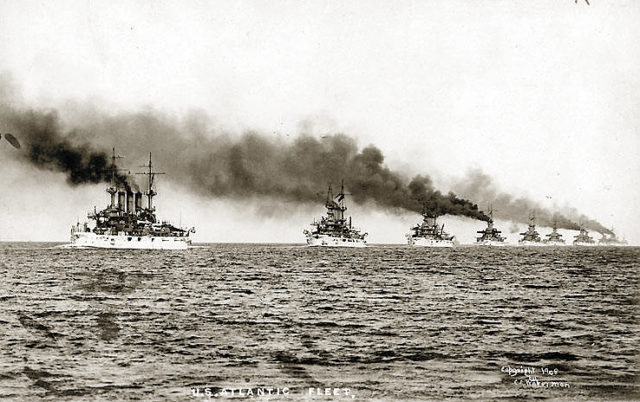

The birth of the American Navy is often attributed to the vote by the Continental Congress in 1775, prompted by a letter from George Washington, to arm two sailing vessels with carriage and swivel guns. This was done in the hopes of intercepting British supplies. This is a surprisingly humble beginning, considering the powerhouse it is today. Its beginning isn’t the only unexpected thing about the seafaring branch of the American armed forces. Below are some more facts that you might not have known about the U.S. Navy.

-

The father of the Navy was George Washington.

Washington_1772.Source

As already mentioned, George Washington and the letter he sent to the Continental Congress is the reason that the Navy was formed. Washington was a huge early supporter of the Navy, despite not having much experience at sea. The reason of his support? He believed that it would serve well to disrupt British supply lines. “It follows then as certain as that night succeeds the day, that without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive, and with it, everything honorable and glorious,” he wrote. He was proactive, however, and instead of waiting for the Continental Congress to act, Washington used his authority as commander in chief of the Army. Under his orders, a small flotilla of fishing schooners were converted into warships. The Hannah, named after the owner’s wife, was the first to depart the Massachusetts coast in September 1775—a whole month before the Continental Congress was informed of Washington’s activities and officially established the Navy. Since then, the Hannah has entered into lore as the Navy’s founding vessel, although it ran aground hardly a month into service and was then decommissioned. Luckily, the rest of Washington’s flotilla fared better. In total, Washington’s Navy captured fifty-five British ships by the time it was dissolved in 1777.

-

The Navy was dissolved following the Revolutionary War.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Navy, state navies, Washington’s flotilla, and privateers all battled the British. Although all the crews were valiant, there are a couple of notable victories. For example, Commander John Paul Jones capture the frigate HMS Serapis, after he had apparently yelled, “I have not yet begun to fight!” That being said, the American presence at sea was relatively minimal compared to that of Britain’s all-powerful Royal Navy. By August 1781 the Continental Navy had shrunk to just two active warships, but luckily, by that time, France had joined the colonists’ side. September 1781 saw a major naval battle, in which the French gained control of the Chesapeake Bay. This would lead the way for the British surrender in Yorktown the following month. After that, the Continental Navy shrunk further, due a lack of both money and a clear reason to maintain it. The last two ships were sold or given away. The last one to go, in 1785 was called the Alliance, a frigate that just two years earlier had participated in the final skirmish of the Revolutionary War at the Florida coast.

-

Pirates were the main reason that the Navy was brought back.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, U.S. merchant ships, without the protection of the British Royal Navy, became the victims of frequent pirate attacks, particularly by the Barbary pirates of North Africa. American sailors were seized and imprisoned in both 1785 and 1793. In order to secure the sailors’ lives and to gain commercial access to the Mediterranean Sea, the United States had to pay tribute to the Barbary states. Spurred by these attacks, the Congress revived the Navy in 1794 and authorized the construction of six warships, including the USS Constitution — a ship that ship remains afloat today in Boston Harbor.

When the ruler of Tripoli tried to declare war in an attempt to extract increased tribute from the U.S. in 1801, the Navy was sent in to deal with the pirates. Although they lost a 36-gun frigate after it ran aground as it chased a blockade runner, the Americans captured the port city of Derna in 1805 during a raid. Then, in 1815, hostilities with another Barbary state, Algiers, broke out. A Navy squadron quickly defeated the Algerian flagship and thus secured a lasting end to the Barbary practice of tribute and ransom.

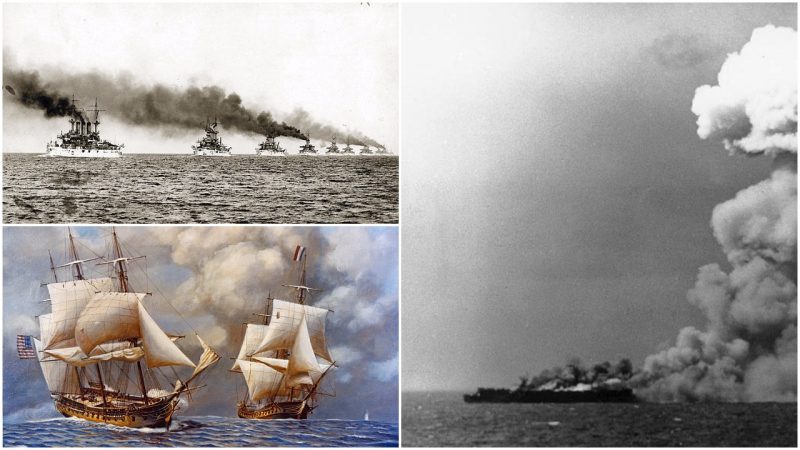

As the decades slid by, the Navy continued to earn in existence. It engaged the French in the Quasi-War (1798-1801), the British in the War of 1812 (1812-1815), and pirates in the Caribbean.

-

Speaking of the War of 1812, the Navy was outnumbered about forty to one.

At the start of the war, the U.S. Navy had a mere sixteen warships, while their British opponents had more than 600. Even though most of the Royal Navy was occupied fighting Napoleon in Europe, they maintained a powerful blockade of the Atlantic coast. The U.S. Navy did have some single-ship successes, however. For example, the USS Constitution took down the HMS Guerriere— this earned it the nickname “Old Ironsides”, supposedly because of how British cannonballs bounced off the Constitution. The main successes that the Americans earned were inland on rivers and lakes. Due to manpower shortages, a prohibition on black sailors was lifted, and African-Americans played a big role in these victories. Thanks to them, American Navy squadrons were able to blast their way to take control of strategically important sites, such as Lake Erie and Lake Champlain.

-

The Navy (indirectly) fought the slave trade, even though slavery was still legal.

It took long enough, but in 1807, Congress finally banned the importation of new slaves into the United States. Slavery was still technically legal, and it flourished in the South. The enforcement of this law was sporadic over the next thirty-five years—the Navy rarely patrolled the west coast of Africa, and they only stopped ships that flew the American flag. On top of that, other countries were forbidden to search ships of suspected U.S. slavers.

Eventually in 1842, the United States and Britain agreed to cooperate to suppress the slave trade. Although it only captured thirty-six vessels in two decades of work, a U.S. Navy squadron was permanently stationed in Africa. Their British cousins, on the other hand, managed to detained several hundred vessels over the same time frame. Critics usually argue that this was probably due to Navy’s leaders’ failure to properly equip the squadron, as well as the southern-born officers who deliberately shirked their duties.

-

During World War II, the Navy produced six future presidents.

Until World War II, no president had served in the Navy. Then, suddenly, it turned into a near prerequisite for reaching the White House. John F. Kennedy had commanded a motor torpedo boat that would be run over by a Japanese destroyer in the Solomon Islands. Lyndon B. Johnson was stationed briefly in New Zealand and Australia, even though he was a sitting member of Congress. Richard Nixon supervised air cargo operations; Gerald Ford served as an aircraft carrier’s assistant navigator and was almost swept overboard during a typhoon. Jimmy Carter attended the Naval Academy and became a submariner after the war. Lastly, Georgy H.W. Bush flew fifty-eight combat missions, including one in which he was shot down over the Pacific. With that kind of record, the only president between the years 1961 and 1993 who did not serve in the Navy was Ronald Reagan.

-

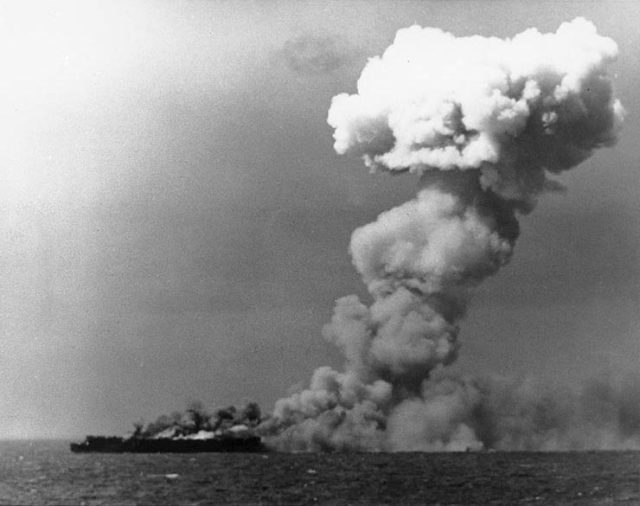

The US Navy won history’s largest maritime battle.

source

During World War II, the Navy fought in numerous major battles, but none were more important than the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the largest naval clash ever in terms of ship tonnage—although it probably wasn’t in terms of number of men or ships. When the U.S. landed forces on the Philippine island of Leyte in October 1944, Japan responded by dispatching virtually every operational warship it had left. In four actions, four Japanese aircraft carriers, nine battleships, nineteen cruisers, some three-dozen destroyers, and hundreds of planes went head to head against thirty-two American carriers, twelve battleships, twenty-four cruisers, more than 140 destroyers, and 1,500 planes. Both the Japanese and the Americans had submarines and small auxiliary boats, but in the end, the U.S. repulsed the attack. This meant the U.S. had essentially undisputed command of the Pacific Ocean for the remainder of the war.