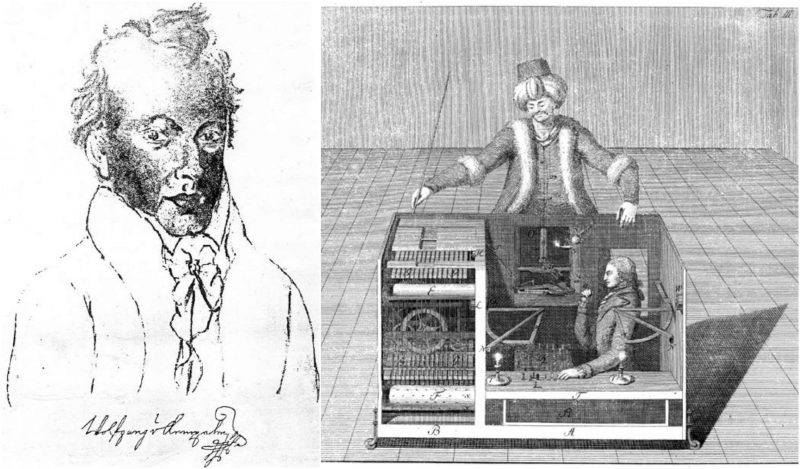

The Mechanical Turk or Automaton Chess Player, most commonly known as The Turk, was an invention by the Hungarian author and inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen. Kempelen constructed the machine in 1770 because he wanted to impress Empress Maria Theresa of Austria.

The Turk was a chess machine that was able to play strong chess games against its opponents. It took the world more than 80 years to discover that the machine which challenged Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin was actually a fraud.

Kempelen became inspired to create the Turk after he saw an illusion show, performed by François Pelletier at the Schönbrunn Palace. So he wanted to have his own show in the same palace, in front of Empress Maria Theresa. To this end, he created the Automaton Chess Player, also known as The Turk.

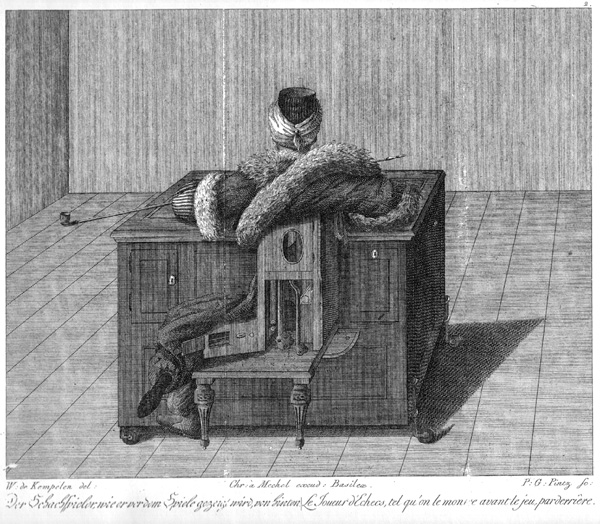

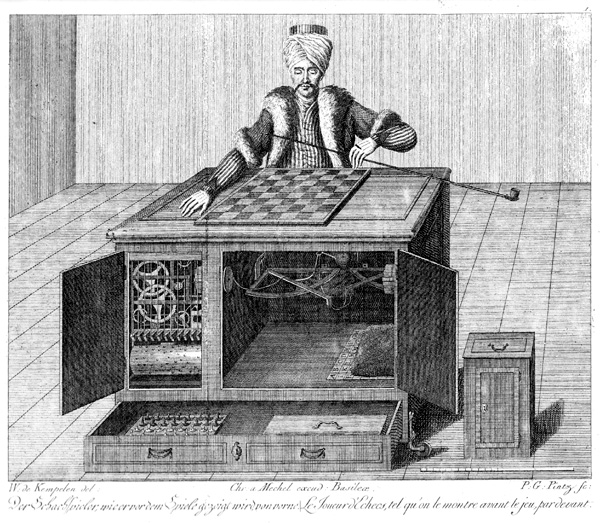

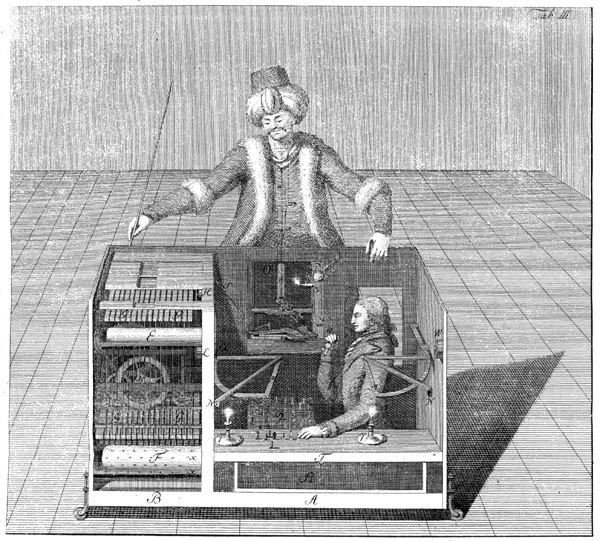

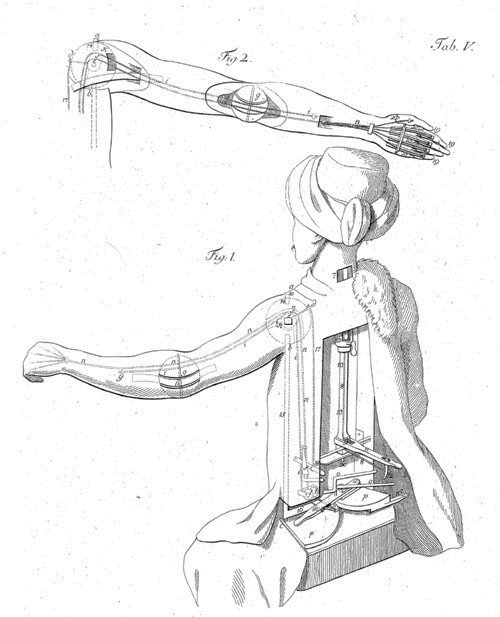

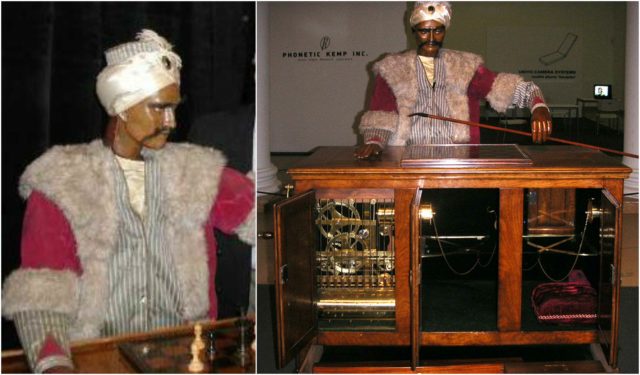

It contained a life-sized human model and a box in front of it with a chess table on its top. The human model had a beard and gray eyes, dressed in “traditional Turkish costume” with a turban on its head, a smoking pipe in its left resting arm and the right arm lying on the board, prepared to make moves.

The whole machine was 110 cm long, 60 cm wide and 75 cm high. Inside the box (under the chess table) contained a very complicated design with many gears and cogs similar to clockwork.

So if anyone observed it and wanted to figure out its “software” work, they would be misled because of the illogical, complicated order in the box. The box had doors everywhere possible so that when presented, the audience could see inside from all angles and wouldn’t doubt that it is genuine.

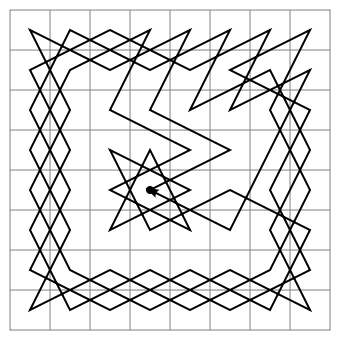

Each piece of the chess set had a strong magnet on its base attached to a string under their specific places on the board. The internal magnets couldn’t be influenced by an outside magnet so Kempelen always encouraged the audience to place magnets next to the board so that they can be convinced that the machine wasn’t any kind of magnetism trick.

Actually, every detail on the machine, even the clockwork sound that it was making when it moved a chess piece on the board, was made to fool the audience that it was genuine. The truth is that inside the Turk was a real human who played the game.

Some of the most notorious chess players who were secretly playing the Turk included Johann Allgaier, Boncourt, Aaron Alexandre, William Lewis, Jacques Mouret, and William Schlumberger.

Kemplen and the Turk traveled all around Europe, fascinating audiences all around, and were invited to the Sanssouci palace in Potsdam of Frederick the Great, King of Prussia.

Frederick was so impressed with the machine that he offered Kemplen a large amount of money so that he would tell him the secret of how the machine worked. Even though he never told the truth about it, Frederick was quite disappointed to learn how the Turk actually played the game.

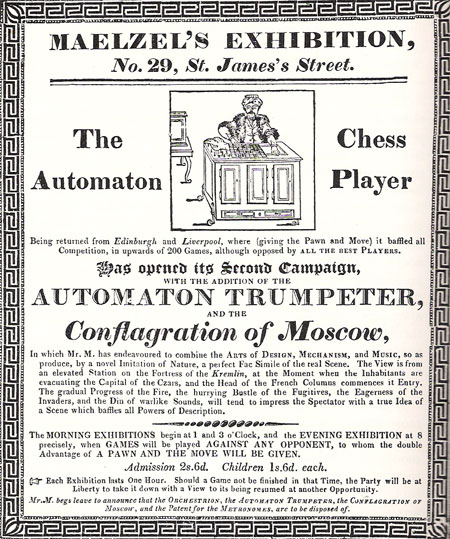

Kemplen died in 1804 at the age of 70 but the Turk remained with its secret unrevealed and known only by a few people. After the death of Kemplen, his son decided to sell the machine to the German inventor, engineer, and showman Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who was famous for patenting the metronome.

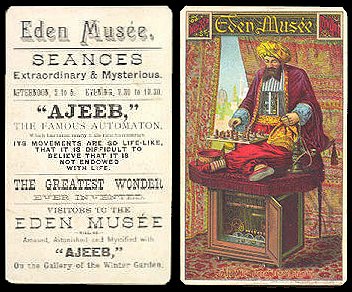

Maelzel wanted to possess the Turk for a while and when he finally acquired it he had to learn how it worked and made a few changes to it before presenting it in front of an American audience in 1826.

In the States, the Turk gained as much popularity as it did in Europe, and even though many articles and even books were published with sketches and explanations about how it worked, nobody got close to the truth.

The Turk outlived his second owner, Maelzel, who died in 1838 and got in the hands of the American physician and writer John Kearsley Mitchell who managed to donate it to the Chinese Museum of Charles Willson Peale where the Turk gave performances.

Unfortunately, a fire that started at the National Theater in Philadelphia reached the Museum and the Turk burned. Mitchell believed he had heard “through the struggling flames … the last words of our departed friend, the sternly whispered, oft repeated syllables, ‘echec! echec!!'”

Many American scientists, professors, and journalist began to slowly notice small things about the Turk that led to different conclusions. In 1859 there was an article saying that the machine might have been invented by the French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin.

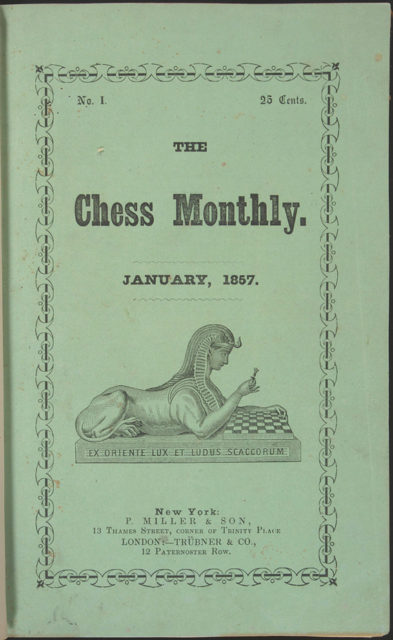

The truth was finally revealed in an article in The Chess Monthly written by Dr. Silas Mitchell.

Mitchell wrote: “no secret was ever kept as the Turk’s has been. Guessed at, in part, many times, no one of the several explanations … ever solved this amusing puzzle.” After the Turk burned, Mitchell, who was actually the son of a private owner of the Turk, thought that there was no reason for the truth not to be revealed.