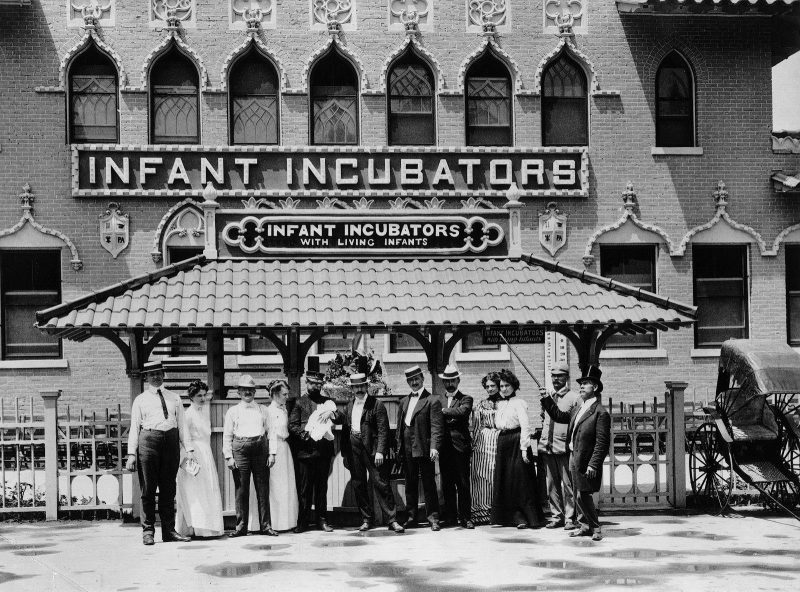

Coney Island in the early 1900s boasted an array of eye-opening sideshows—Midget City (a village with 300 little people living inside), reenactments of real-life natural disasters (including the San Francisco Earthquake and 1902 Johnstown Flood), and Lionel the Lion-faced Man, among them.

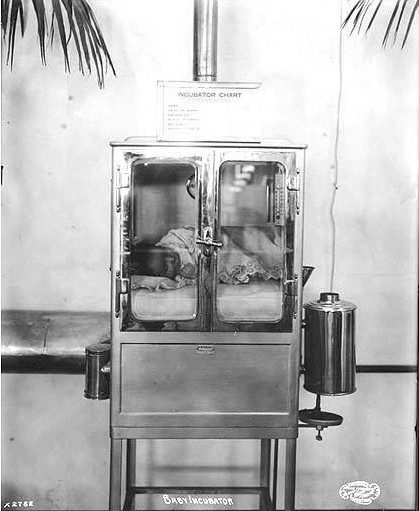

But perhaps the most jaw-dropping attraction of all: rows of tiny, premature babies, living in glass incubators and fighting to survive, as the paying public looked on.

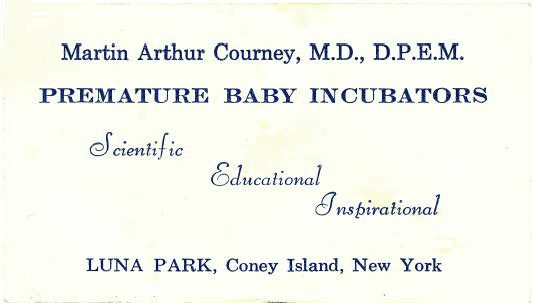

The man behind the exhibit was French-born Martin Couney, dubbed “the incubator doctor.” There aren’t a lot of people today who know his name, but Couney was a pioneer in the treatment of babies who were born premature, saving the lives of literally thousands of little ones. Pretty astounding, since Couney wasn’t a renowned physician. In fact, some believe he wasn’t a licensed doctor at all.

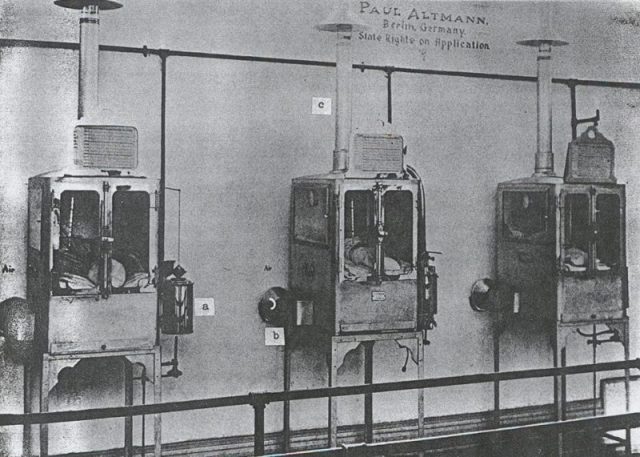

It was at the Berlin Exposition, in 1896, that Dr. Couney saw the newfangled glass and metal incubators, and hatched a plan to bring them to the United States.

Starting in 1903, the Coney Island boardwalk became his home turf. A banner that read, “All the World Loves a Baby” hung outside the entrance of the exhibit.

Visitors paid 25 cents to get a glimpse of the tiny preemies, encased in rows of incubators and tended to by a team of nurses and wet nurses who lived onsite, along with two physicians. Many of the infants in the exhibit came to Couney from local hospitals that couldn’t care for them.

The medical establishment was appalled by the exhibit, deeming it exploitative, and accused Couney of being a fraud. There were regular attempts to shut him down. At the time, in the U.S. anyway, doctors believed that premature babies were lost causes and left their fates in the hands of God.

Couney vehemently disagreed, countering that his facility was technically a hospital, not some quirky sideshow attraction—and, under the care of he and his team, the infants stood a fighting chance.

Bolstering his argument: Couney practiced what he preached. His own daughter, who had been born prematurely, actually spent time in one of her father’s exhibits.

Premature Babies Really Were Displayed On Coney Island

Indeed, Couney’s techniques were cutting edge for the time. His incubators were imported from France, at that time the leader in preemie care. He insisted his babies be fed breast milk and encouraged nurses to take the babies out of their incubators to cuddle and kiss them (unlike mainstream doctors who believed contact should be kept to a minimum), and even employed a special cook to prepare vitamin-packed meals for his wet nurses.

Couney also took in babies from all races and backgrounds, a pretty progressive move back in the day. Of course, this kind of care didn’t come cheap. In 1903, it cost around $15 (the equivalent of $405 today) a day, yet parents didn’t pay a cent.

The public came in droves, more than covering the operating costs. Even so, Couney wasn’t above employing coy tricks to keep the turnstiles moving—including dressing the babies in oversized clothes to accentuate their tiny, frail bodies.

In the years to come, Couney would set up similar facilities at Atlantic City, as well as take his show on the road to other amusement parks and World’s Fairs across the country By the 1930s, the stubborn medical community was coming around, offering Couney their begrudging respect. Some doctors sent premature babies to Couney to care for.

In fact, it wasn’t until after his death in 1950 that incubators became a mainstay in maternity wards across the country.

But perhaps the numbers best demonstrate the good doctor’s extraordinary achievement best: Over the course of his nearly 50-year career, Couney cared for about 8,000 babies and claimed to have saved approximately 6,500 of them—a stunning survival rate of 85 percent.

_______________________________________________________________________

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.