“This is a work of fiction. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is purely coincidental.”

The “all persons fictitious” disclaimer has appeared in the opening credits of countless movies since the 1930s. Indeed, this small piece of legal boilerplate is often included even when it is perfectly obvious that the subject of the movie is a real (or fictitious) person.

For example, the filmmakers of Raging Bull, the iconic biopic of Ray LaMotta, included the “all persons fictitious disclaimer” in the credits, despite also crediting LaMotta as a consultant and explicitly basing the movie on his memoir.

Why, then, does this strange and somewhat nonsensical Hollywood convention persist, even today? According to The Yale Review, the little-known story behind the disclaimer’s first appearance involves a Russian prince, an expensive lawsuit, and the infamous mystic Grigori Rasputin.

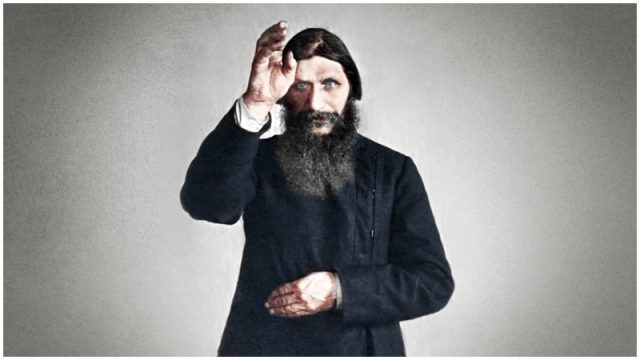

Rasputin is one of the most notorious figures in imperial Russian history. A self-proclaimed “holy man”, he came to prominence as a favored mystic and healer in the court of Tsar Nicolas II, the last of the imperial Romanov dynasty.

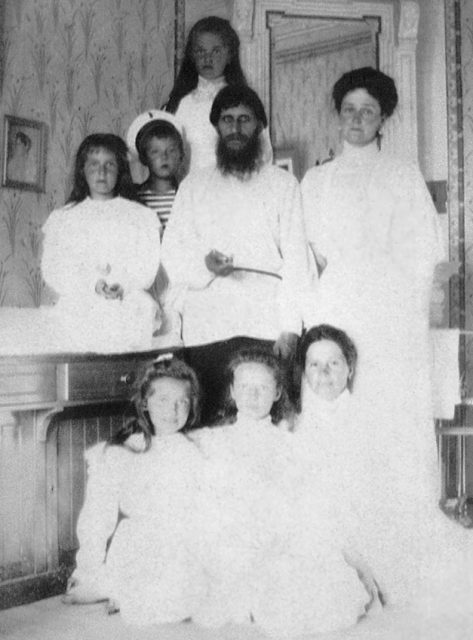

Born a lowly peasant, Rasputin’s fortunes changed dramatically when he came to work as a healer in the court of the Tsar, winning particular favor with the Tsarina, Alexandra Feodorovna. According to the BBC, Rasputin was a divisive figure and was deeply unpopular with Russian aristocrats who feared his influence over the Tsar’s family.

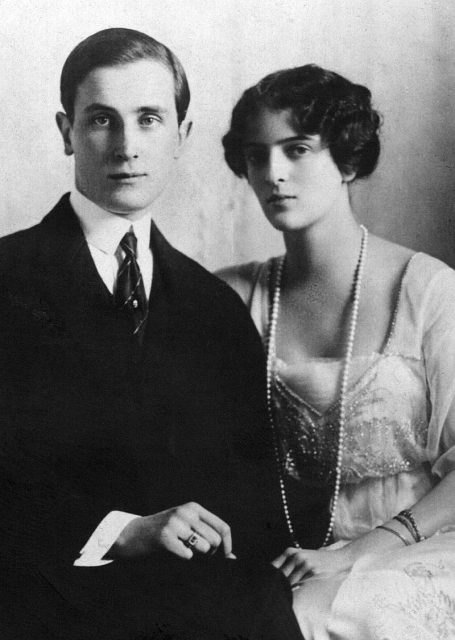

His life, character and deeds are shrouded in myth, and he has emerged as a key scapegoat in Russian history, taking the blame for many of the unpopular policies and misdeeds of the Russian imperial regime in its final years. Ultimately, Rasputin’s fall from grace was swift and brutal: in December 1916 a wealthy Russian aristocrat, Prince Felix Yusupov, invited him to stay at his palace in St. Petersburg.

According to Yusupov’s own memoirs, he fed the mystic tea, cakes and wine that had been laced with poison, and when Rasputin appeared to have no reaction to the concoction, shot him. Rasputin again survived this, but later after further damage inflicted upon him drowned in the Neva river after terrifying everyone with his resilience.

The murky details surrounding Rasputin’s story make it particularly compelling, and it’s no surprise that only a few years after his untimely demise, movie studios were grappling to immortalize him on the big screen.

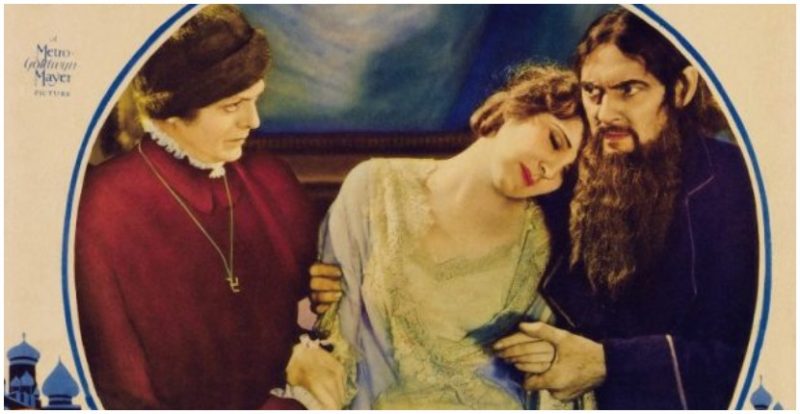

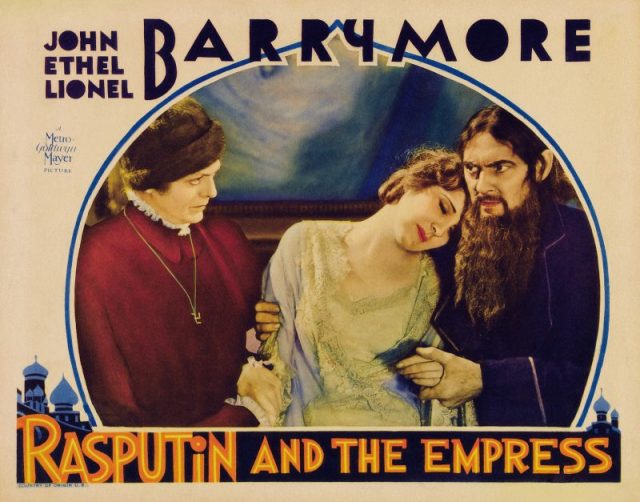

In 1932, MGM released Rasputin and the Empress, a huge blockbuster with a glittering cast, which provided a sensational account of Rasputin’s rise to power and his close relationship with the Tsarina.

However, Prince Yusupov, still alive and by this time living in relative poverty, strongly objected to the representation of Rasputin’s death in the film, fearing that it would impact his reputation.

The movie did not explicitly mention Yusupov, but the character of Prince Paul Chegodieff, who was depicted as Rasputin’s murderer, was clearly based on the real-life Prince Yusupov.

Yusupov could scarcely sue the studio for defamation: after all, he had himself admitted to Rasputin’s murder in his own memoirs, published just a few years previously. However, his wife built a case against the studio, arguing that she was unfairly represented in the movie.

According to Slate, the writers had included a fictional scene in which the Prince’s wife was violated by Rasputin, an event that had never occurred in reality. Princess Irina, Yusupov’s wife, argued that this amounted to severe defamation of her own reputation.

Incredibly the case was successful and Irina was awarded over $127,000, the equivalent of almost $2.4 million today. The judge informed the studio that their mistake had been to acknowledge that the movie was based on a true story: had they denied that their characters were rooted in reality, they could have mounted a defense of plausible deniability.

Read another story from us: The Violent End of Rasputin – Details of his Fateful Last Night

After this landmark case, movie studios weren’t taking any chances. The “all persons fictitious” disclaimer was always included as a routine convention and endured for decades, even in works that were clearly based on historical events. This disgruntled Russian prince and his brutal exploits with the mysterious Rasputin had an unexpected and enduring impact on the course of Hollywood history.