We are continuously fascinated with ancient civilizations and their ability to move giant stones.

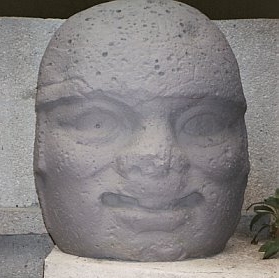

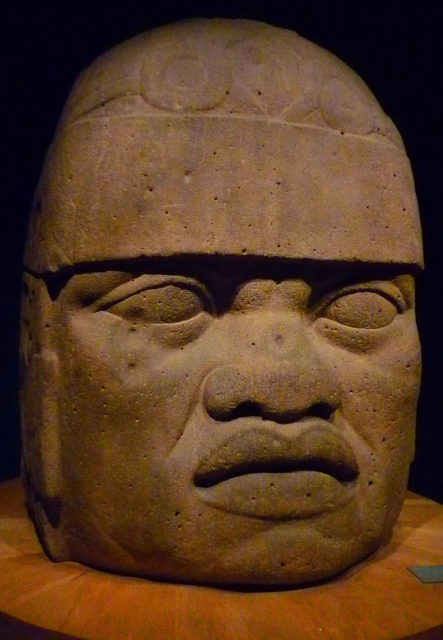

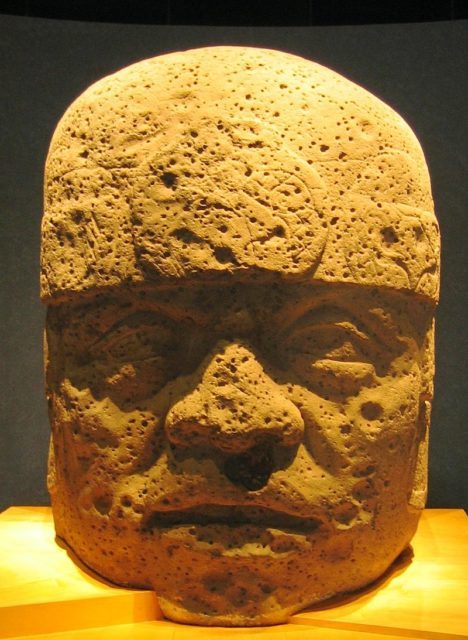

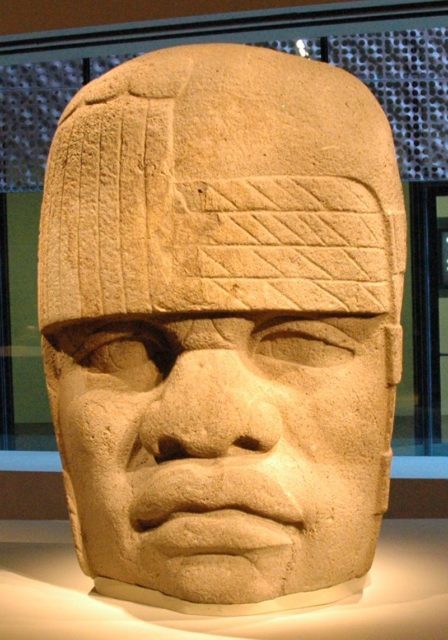

One of these mysteries concerns the Olmec civilization and their carvings of stone heads that have been discovered in Mexico. These gigantic sculpted stone heads portray ancient men with flat noses, slightly crossed eyes, and chubby cheeks. So far, seventeen of these colossal stone heads have been unearthed, and nobody knows why they are located, where they are or how they got to that location.

The first archaeological exploration of the Olmec civilization occurred in 1938. These expeditions took place quite a long time after the discovery of the first gigantic head in 1862 at Tres Zapotes. These seventeen Olmec Colossal Heads were found at four sites along the Gulf Coast of Mexico, within the heartland of the Olmec civilization.

Most of the Olmec stone heads were sculpted from round, circular boulders, but two of the colossal heads from San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán were sculpted from gigantic stone thrones, previously carved from stone boulders. Curiously, another monument, a massive stone throne located at Takalik Abaj in Guatemala, may have been carved from a colossal head! This monumental throne is the only known example of a colossal carving from outside the Olmec heartland.

Precise dating of the colossal heads is not yet entirely established. Scientists have examined the four locations of the Olmec heads – San Lorenzo, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, and Rancho la Cobata – to get an idea of how they are related. The San Lorenzo monumental heads had been buried around 900 BC, which clearly indicates that their construction and use was earlier than that. These show the most precise skill and are thought to be the oldest of all the carved heads. The dating of the other sites is more difficult – the sculptures at Tres Zapotes had been moved from their original setting before they were explored by archaeologists, and the monuments at La Venta were partially uncovered on the ground when they were discovered.

So the actual period of the construction and completion of the Olmec Colossal Heads could span a hundred years or a thousand years. All of the Olmec stone heads are a distinct aspect of ancient Mesoamerican times and have been categorized in the Early Preclassic period of 1500 BC to 1000 BC, although the two heads at Tres Zapotes and the Rancho la Cobata head are recognized as being from the Middle Preclassic period of 1000 BC to 400 BC.

The heartland of the Olmec civilization was situated on the Gulf Coast of Mexico; it comprised a land mass area of nearly 62 miles inland from the Gulf shores and extending 171 miles, encompassing the two present-day states of Tabasco and Veracruz. The Olmec civilization is considered the first culture to advance in Mesoamerica, developed in this area of Mexico between 1500 BC and 400 BC. As one of the “Six Cradles of Civilization” in the world, the heartland of the Olmec civilization is the only one that was developed in a low-lying, tropical forest location.

The carving and placement of each colossal stone head has been approved and coordinated by powerful Olmec rulers. Construction had to be carefully planned, considering the effort involved in obtaining the necessary resources. So it seems that only the most influential could mobilize such resources. The vast labor force included sculptors, boatmen, laborers, woodworkers, overseers, and other artisans, creating the utensils to make and move the sculpture. In addition to these was the personnel required to feed and attend to these scores of workers. Additionally, the seasonal cycles, agricultural phases, and river levels had to be taken into consideration to plan the production of the enormous sculptures. The whole project, from beginning to end, could have taken years.

Archaeological examination of the Olmec basalt work spaces suggests that the stone heads were systematically shaped and finished. First, they were roughly formed by striking the stone directly, chipping away both large and small fragments of rock.

The sculpture was then enhanced by refining the surface using hammer stones, which were rounded flagstones that could be fashioned from the same basalt stone as the monument itself. Abrasives, which research has indicated were utilized in the finishing stages of the fine detail of the sculptures, were found in correlation with work spaces in San Lorenzo.

The Olmec Colossal Heads were fashioned as free-standing sculptures with differing levels of sculptural relief on the same stone. They had a tendency to feature higher relief on the face and lower sculpting relief on the headdresses and jeweled ear-spools. In San Lorenzo, an extensively damaged monument is a stone throne with a figure emerging from a hollow in the throne. Its sides were shattered, and it was abandoned after being dragged to another location. This damage could have been caused by the initial stages of the relief carving of the throne into a colossal head, but it is impossible to determine because the work has never been completed.

All seventeen of the Olmec Colossal Heads, situated in the civilization’s heartland, were sculpted from basalt stone from the Sierra de los Tuxtlas Mountains in the state of Veracruz. An ancient volcano in the mountain range formed the coarse-grained, dark gray basalt boulders used in the construction of the statues– this is known as Cerro Cintepec basalt. These large basalt boulders originated on the southeastern slopes of the mountains and are the source of the stone used for all the monuments.

These boulders were found in an area affected by large volcanic mudslides that carried huge boulders down the mountain slopes. The Olmecs carefully selected spherical boulders that simulated the shape of a human head. The boulders were transported over 93 miles from the mountain slopes. It’s practically unknown how the Olmecs transported such huge masses of basalt, especially since they had no animals that could pull burdensome loads and no functional wheels. Most likely they had to use water transportation whenever possible.

The Olmec Colossal Heads vary in weight from between six to fifty tons and are approximately five to twelve feet high. The overall physical characteristics of the heads resemble the people living in the Olmec region in modern times. The rear of the stone monuments is often flat, indicating that they were initially placed against a wall, which would have provided support while the carvers were working.

All examples of the Olmec Colossal Heads have unique headdresses that most likely signify animal hides or cloth. Some of the stone heads even show a tied knot at the back of the head, and some are embellished with feathers. There are few similarities among the headdresses on the stone heads, leading to the theory that specific headdresses may symbolize a specific dynasty or possibly identify individual rulers. Most of the Olmec Colossal Heads have large ear-spools inserted into the ear lobes.

All of the heads are realistic replicas of the sculpted men. It is probable that they were portrayals of current rulers or recently departed, and the subjects were quite well known to the sculptors. Each head is distinct and realistic, exhibiting individualized characteristics.

All the 17 confirmed colossal heads are still in Mexico. Two heads from San Lorenzo are permanently displayed in Mexico City at the National Museum of Anthropology. Seven of the San Lorenzo heads are exhibited in the Anthropology Museum of Xalapa. The last remaining San Lorenzo head is in the Community Museum of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan, near Texistepec. The four Olmec heads from La Venta are currently in Villahermosa, the state capital of Tabasco. Three of them are in the La Venta Museum Park, and one is in the Museum of History of Tabasco. Two more of the stone heads are on display in the Hotel Gran Santiago Plaza Tuxtla along with another from Tres Zapotes and Rancho la Cobata. The other Tres Zapotes head is in the Community Museum of Tres Zapotes.

Several of the Olmec Colossal Heads have been outside of Mexico, temporarily loaned to exhibitions abroad. The San Lorenzo Colossal Head #6 was loaned to New York City in 1970 for an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1996 Washington, D.C. accepted a loan of the San Lorenzo Colossal Heads #4 and #8 for the “Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico” exhibition in the National Gallery of Art. In 2005, San Lorenzo Head #4 was once again loaned out, this time to the Young Fine Arts Museum in San Francisco. In 2011, San Lorenzo Colossal Heads #5 and #9 were on exhibit at the Young Fine Arts Museum for its Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico exhibition.