Today workers take for granted that a standard work week has 40 hours, spread over five days. There are variations of that formula, of course, and some percentage of workers work a certain amount of overtime, as well. A 40-hour working week is a relatively recent practice, though.

The U.S. had a few limited eight-hour-day laws that went on the books not long after the Civil War. In 1867, one was passed in the state of Illinois, and another was passed the following year that covered certain federal employees, but enforcement was weak, and most people were still working 10 and 12 hour days, especially in manufacturing. So how did our present model come about, then?

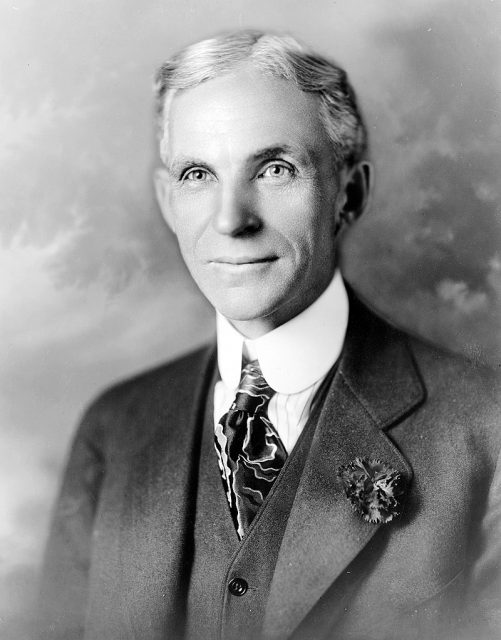

In 2015, Politifact was sent a meme that gave the credit for our forty-hour, five-day work week not to labor unions, but to Henry Ford of the Ford Motor Company, and was asked to check it out. This is what they found.

In the late 19th century, the length of a worker’s day was becoming more and more of an issue for the growing labor movement.

The first big push for an eight-hour limit to the working day came to prominence in 1884, and called for all workers to have an eight-hour work day by May 1, 1886. The deadline wasn’t met, so labor leaders began calling for demonstrations to emphasize the issue.

Sometimes those demonstrations, which were meant to be peaceful, broke into violence, such as when there was an explosion at a rally in Haymarket Square in Chicago on May 4, 1886, leaving several dead. That incident kept the issue at the forefront of public social and political discourse, but no decisive changes were made. All of that happened long before Henry Ford entered the picture.

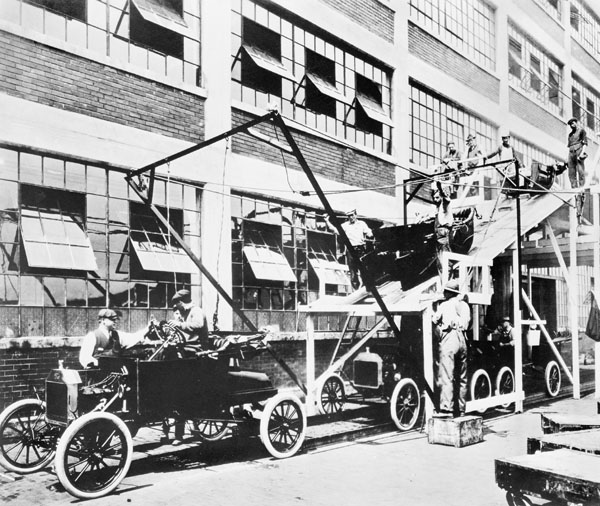

In 1914, Henry Ford made the announcement that he was raising the wages of all his male workers from $2.34 to $5 an hour, more than doubling their current hourly rate, and scaling back from their then-48-hour work week to a 40-hour work week.

Ford believed that overworking employees was bad for their productivity, and giving them more down time without compromising their financial well-being would help increase worker loyalty and commitment to Ford Motor Company.

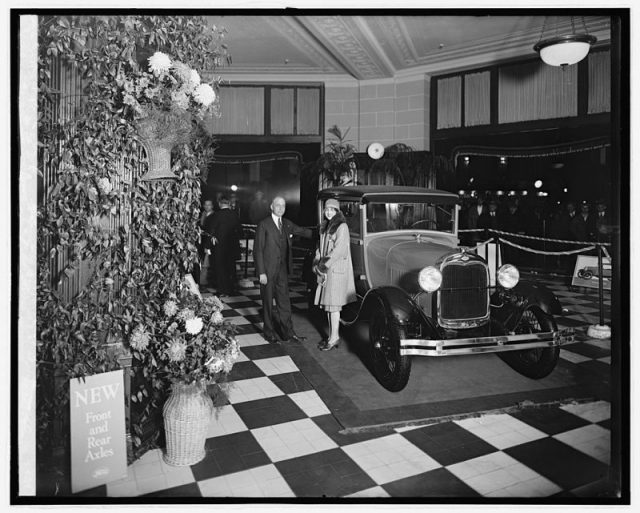

Other companies started to emulate Ford’s policies about working hours when they saw that Ford Motor Company’s profits nearly doubled over the subsequent two years.

Ford’s reasons for making those changes had other, less employee-focused motivations as well, though. In a 1926 interview with Henry Ford in World’s Work, it suggests that his motivations were also capital driven.

In the interview, Ford stated that that leisure time should not be considered “lost time” and shouldn’t be just for the privileged class; he believed that workers needed free time to actually be able to purchase and use consumer products which would increase business. Watch some rare Henry Ford footage from 1915-30 below:

Henry Ford’s son, Edsel, later told the New York Times that “Every man needs more than one day a week for rest and recreation…The Ford Company has always sought to promote [an] ideal home life for its employees. We believe that in order to live properly, every man should have more time to spend with his family.”

Johnson Hur, writing for BeBusinessed, notes that Ford’s actions gave a boost to the American labor movement, encouraging the growth and development of more labor unions as they rallied around the idea of a five-day, eight-hour-shift workweek.

Ford’s groundwork and a great deal of effort from the new labor unions all came to a head in 1937, when workers at General Motors staged a sit-down strike in Flint, Michigan.

The strike brought together two different unions, General Motors, and the federal government, ultimately improving working conditions at GM, but also paving the way for the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which was part of FDR’s New Deal.

The FLSA didn’t just cover the length of the workweek. It also addressed overtime pay, put restrictions on child labor, and instituted a minimum wage, all of which were revolutionary departures from the standard practices that arose during the Industrial Revolution.

Read another story from us: How a 17th Century Revolutionary Gave us the Word “Guy”

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our Today In History newsletter!

Ultimately, whether Ford’s decision to change his model for operations was driven primarily by concern for his employees or by the desire to sell more cars matters much less than its end result; it paved the way for much fairer and kinder working conditions for the country’s labor force.