The word “guy” is one of the most ubiquitous terms in modern English. It’s used casually every day in the English-speaking world, often to refer affectionately or flippantly to an individual, or group of people.

However, very few people realize that this word actually has its origins in a foiled 17th-century coup attempt, still commemorated by some in the United Kingdom every year on the 5th of November.

According to The Washington Post, the word “guy” comes from Guy Fawkes, conspirator in the Gunpowder Plot and the focus of the annual Bonfire Night celebrations in the United Kingdom.

In 1605, a group of English Catholic dissidents were conspiring to orchestrate a regime change. England was ruled by the Protestant King James the VI and I, and conditions for Catholics were extremely difficult.

When James acceded to the English throne in 1603 many Catholics held high hopes that he would put an end to the persecution that had dominated their lives under his predecessor, Elizabeth I. However, when by 1605 James showed little sign of changing the status quo, many Catholics began to call for more drastic measures.

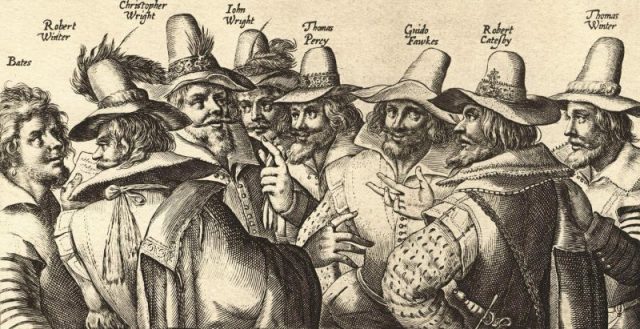

A group of thirteen conspirators, led by Robert Catesby, planned to do away with the king and his key advisors by blowing up the House of Lords during the state opening of Parliament in November 1605.

This was a public event at which all the major political figures in the country would be gathered, including the king himself. It was a plot designed to strike a blow at the very heart of government in England.

According to The Washington Post, the plan was to hide a vast quantity of gunpowder underneath the English Parliament, primed and ready to go off during the state opening.

One of the plotters, named Guy Fawkes, was charged with preparing and lighting the gunpowder. However, an anonymous tip exposed the plan and Fawkes was caught at the scene of the crime, surrounded by 36 barrels of gunpowder.

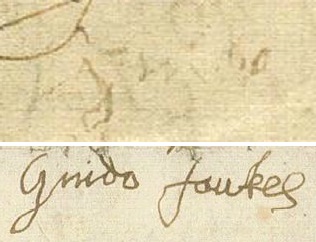

Fawkes was tormented on the rack, a terrible trial that probably left him with several broken bones. He gave up his fellow conspirators, and confessed everything he knew about the plot.

Along with other captured plotters, he was sentenced to death by the most terrible method of the time, reserved only for traitors: he would be hanged, drawn and quartered, and his broken body displayed at the Tower of London as a message to any other would-be plotters.

In the end, Fawkes threw himself from the scaffold before he could be hanged, thereby breaking his neck and saving himself from an excruciating, slow demise.

The Gunpowder Plot and its discovery had a huge impact in England during the years that followed. Repression of Catholics increased even further, and James became increasingly paranoid about other potential attempts on his life.

A law was passed that mandated the commemoration of the event on the 5th of November, and within a few years, the tradition of ringing church bells and lighting bonfires had become standard practice. Over time, this commemoration evolved into a folk holiday, known as Bonfire Night.

Today, on Bonfire Night, people across England light bonfires and watch fireworks to mark the anniversary of the foiled plot. Most strikingly, children create effigies of Guy Fawkes, which are then burned on the fire.

These effigies, made of old clothes, straw and newspaper are known as “guys”, and in England, until relatively recently, “guy” referred to a man of unkempt appearance or poor reputation.

However, in the United States, divorced from its historical context, the word “guy” lost its negative connotations and became simply a popular way to describe a man. According to Business Insider, today it can even be used as a gender-neutral term to refer to a group of people. Certainly, few people associate this word with its explosive origins.

Nevertheless, the tradition of setting ablaze “guys” continues in the United Kingdom, and the legacy of Guy Fawkes has permeated into popular culture, including in the 2005 dystopian thriller V For Vendetta.

So, next time you call out “you guys” to your friends, remember, remember Guy Fawkes, Bonfire Night and the failed Gunpowder Plot that nearly got rid of a king.