The town of Hamelin in Hanover, northern Germany, is often linked with the legend of the Pied Piper. But another legendary man is associated with the area, and while there is some debate over whether the Pied Piper was a real person, there’s absolutely no doubting that Peter the Wild Boy existed. In fact, a painting of him graces the walls of Kensington Palace in England.

Discovery and royal patronage

Peter’s exact date of birth is not known because he was found wandering wild in the woods near Hamelin in 1725. He was discovered by a hunting party led by George I of England, who was visiting his Hanover homeland.

The hunting party was intrigued by the boy, who appeared to have been living a feral existence. Details about his discovery were included in the parish register of St. Mary’s Church, Northchurch, Hertfordshire: “In the year 1725, he was found in the woods near Hamelen… He was supposed to be then about twelve years of age, and had subsisted in those woods upon the bark of trees, leaves, berries &c. for some considerable length of time. How long he had continued in that wild state is altogether uncertain; but that he had formerly been under the care of some person was evident from the remains of a shirt collar about his neck.”

King George’s daughter-in-law, Caroline of Ansbach, the Princess of Wales, arranged for Peter to be transported to Great Britain in 1726. When he arrived in London, he became something of a “human pet” at court. He would scamper around, pick pockets, and even try to steal kisses.

There had been stories of feral children before, but according to Lucy Worsley, curator of Historic Royal Palaces, when she spoke to the BBC in 2011, Peter caused particular interest: “People were beginning to question established authority and religion. And they were interested in what distinguishes us from animals. If he has no speech, does that mean he has no soul? Do human beings really have souls? He raised a lot of philosophical questions.”

His interest also aroused the attention of satirists such as Jonathan Swift and Daniel Defoe. Swift and an unidentified co-author (suspected to be Dr. Arbuthnot) produced a pamphlet called The Most Wonderful Wonder that ever appeared to the Wonder of the British Nation.

The novelty wears off

However, despite public interest, the king and his courtiers soon grew bored of Peter. Attempts to teach him to speak had utterly failed, and servants struggled to get him to wear clothes every day as he much preferred to be naked. His table manners were shocking, and rather than sleep in a bed, he would curl up in a corner of his room.

Princess Caroline took over his care and sent him to live on a farm in Northchurch, Hertfordshire. James Fenn, a yeoman farmer, was paid £35 a year to care for Peter. When James passed away, his brother, Thomas, cared for Peter and received the same government payment.

While Peter didn’t seem to be unhappy at the farm, he did have a habit of wandering off. In the summer of 1751, he went missing. Notices were placed in all the newspapers. It was through a description of him in the London Evening Post that he was identified as a prisoner in the parish of St. Andrew’s in Norwich. He was returned to the farm.

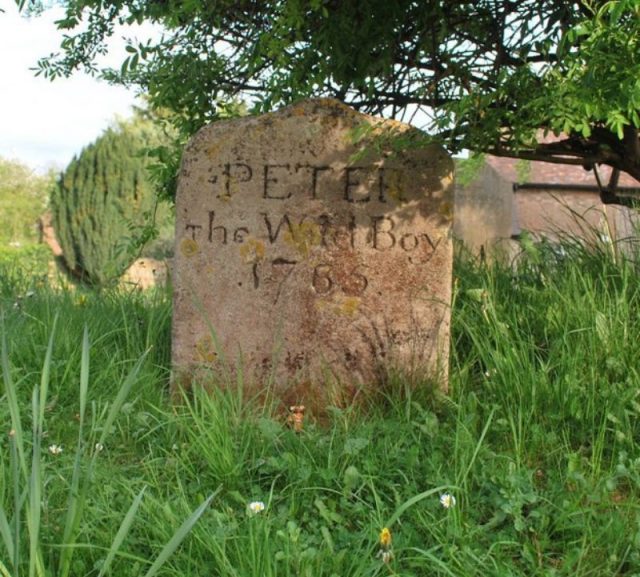

After that incident, the farmers made him a collar to wear around his neck. Lucy Worsely commented: “It looks like the collar of a dog or a slave. But it was made with a kind thought… The inscription read: ‘Peter the Wild Man of Hanover. Whoever will bring him to Mr. Fenn at Berkhamsted shall be paid for their trouble.’”

A relatively peaceful life

After the Oxford scholar Thomas Burgess visited Peter, who wrote to Lord Monboddo with various observations, one of which included how Peter liked to help his master (the farmer he was currently living with).

He would happily engage in work but needed constant direction, as one story illustrated: “Peter was employed one day with his master in filling a dung-cart. His master had occasion to go into the house for something, and left Peter to finish the work. The work was soon done. But Peter must have something to employ himself; and he saw no reason why he should not be as usefully employed in emptying the dung out as he was in putting it into the cart. When his master came out, he found the cart nearly emptied again; and learned a lesson by it, which he never afterwards neglected.”

The parish register also spoke about his love of music and his particularly gentle nature: “All those idle tales which have been published to the world about his climbing up trees like a squirrel, running upon all fours like a wild best, &c. are entirely without foundation; for he was so exceedingly timid and gentle in his nature, that he would suffer himself to be governed by a child.”

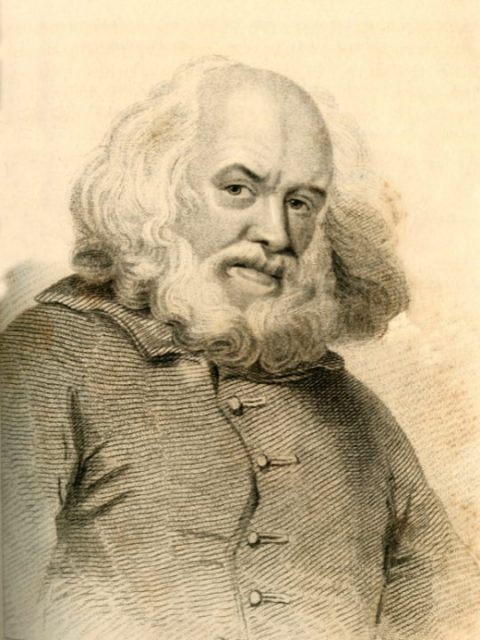

Peter lived well into old age. In 1782, he was said to have a healthy complexion and a great white beard. He still couldn’t talk, but he seemed to understand what was said to him and could at least say his own name and hum a few songs. He liked gin, had no idea what to do with money, and could be found “growling and howling” when bad weather was due.

Such was the fondness of the locals for Peter that when he finally passed away in February 1785, the villagers paid for his headstone. The grave was given Grade II listing in February 2013, and even today fresh flowers can sometimes be found on his grave.

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome

There have been many feral children discovered throughout the ages, and attempts to teach them to talk or reintegrate into society have routinely failed. Quite often, descriptions seem to indicate that the children had mental or physical impairments.

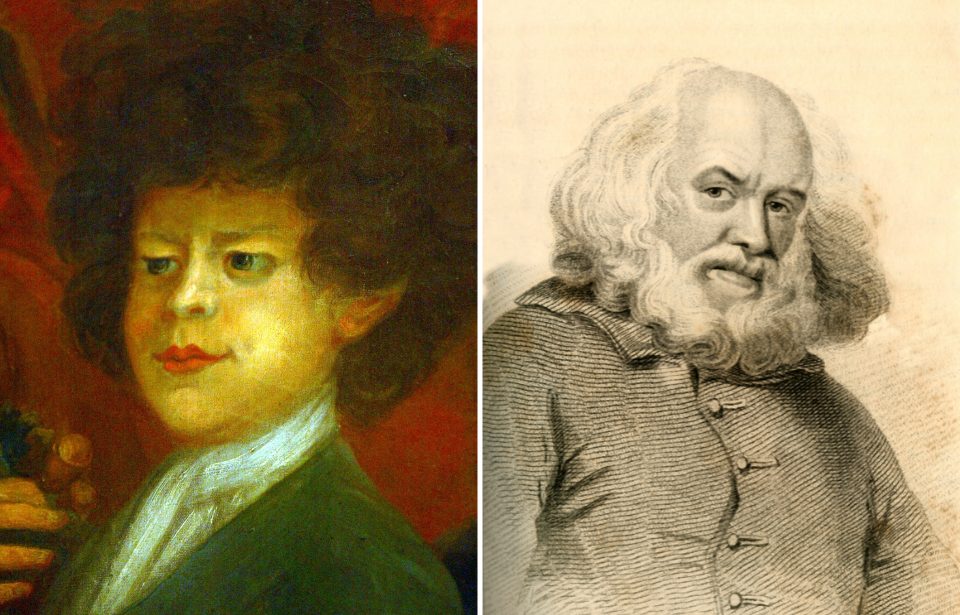

In the case of Peter, it was suspected that he suffered from autism, but curator Lucy Worsley managed to shed light on the truth based solely on examining a portrait of him.

Key physical features of Peter were that he was quite short, had thick, curly hair that was rather unruly, hooded eyelids, and a Cupid’s bow mouth. Added to this was his inability to talk and his dislike of clothes. Lucy Worsley asked Professor Phillip Beales from the Institute of Child Health to run all these characteristics through a database of conditions to see if he could find a match. He did: Pitt-Hopkins syndrome.

Pitt-Hopkins syndrome was only identified in 1978, and a key feature of it is that the patient usually has Cupid-bow lips. Professor Beales says it is characterized by “severe learning difficulties, developmental difficulties and the inability to develop speech.” This list certainly matches descriptions of Peter.

Tragic origins

This new medical discovery suggests that Peter might have been abandoned by his parents due to his severe learning difficulties and behavioral issues.

The parish register offered some thoughts on his parentage: “As Hamelen was a town where criminals were confined to work upon the fortifications, it was then conjectured at Hanover that Peter might be the issue of one of those criminals who had either wandered into the woods, and could not find his way back again, or, being discovered to be an idiot, was inhumanely turned out by his parent, and left to perish, or shift for himself.”

But Peter was luckier than some. Although he was treated like a pet to begin with, he was eventually given the opportunity to live in relative comfort and peace. His royal patrons meant that he was never exhibited as a circus exhibit or a freak, as some feral children were.

More from us: Micronations Are Magnificent But Minuscule — From Asgardia To Sealand

Lucy Worsley’s findings are included in her book Courtiers, published in 2010. She also spoke about it to the BBC Radio 4 program Making History.

Her investigation into Peter’s life had been prompted by a fascination she held for a painting on the king’s grand staircase at Kensington Palace, painted by William Kent in the 1720s. “It’s hugely satisfying to winkle another secret out of the painting, which I’ve been obsessed with for some years now,” she told The Guardian in 2011.