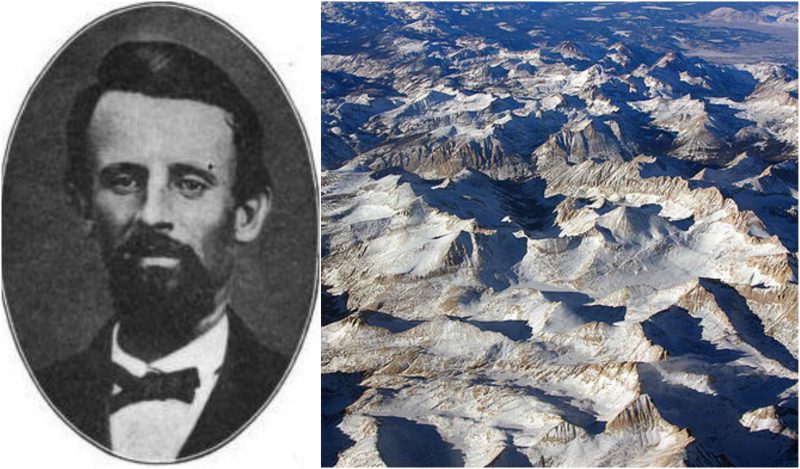

The Donner Party (sometimes called the Donner-Reed Party) was a group of westbound emigrants who became trapped in the Sierra Nevada Mountains during one of the most brutal winters on record. The pioneers were forced to spend five months hunkered down in makeshift tents and cabins with almost no food or supplies.

By the time they were finally rescued in early 1847, nearly half of them had perished. Many of the rest—including the children—were forced to cannibalize the bodies of the dead to survive.

At the beginning of the spring in the year 1846, an appealing advertisement appeared in the Springfield, Illinois, Gazette. It declared: “Westward ho, who wants to go to California without costing them anything?

As many as eight young men of good character who can drive an ox team will be accommodated. Come, boys, you can have as much land as you want without costing you anything.” The notice was signed G. Donner, George Donner, leader of what was to become the most famous, tragic, now nearly mythic Donner Party.

So, April 16, 1846, a group of nearly 90 emigrants left Springfield in twenty wagons on the 2500 mile journey to California, in what would become one of the greatest tragedies in the history of westward migration. Led by two wealthy brothers, Jacob and George Donner, the emigrants initially followed the regular California Trail westward to Fort Bridger, Wyoming. However, the trek had been organized by James Reed, a businessman who hoped to prosper in California and before leaving Illinois, he heard of a newly discovered route through the Sierra Nevada Mountains that promised to cut as many as 300 miles off their journey.

Trip started dangerously late in the pioneer season

Emigrants needed to head west late enough in the spring for there to be grass available for their pack animals, but also early enough so they could cross the treacherous western mountain passes before winter. First of all, out of unknown reasons the party didn’t leave Independence, Missouri until May 12. On May 25, the train was held for several days by high water at the Big Blue River near present-day Marysville, Kansas. It was here that the party experienced the first death when Sarah Keyes died and was buried next to the river. After building ferries to cross the water, the party was on their way again, following the Platte River for the next month. One of the emigrants wrote: “I am beginning to feel alarmed at the tardiness of our movements, and fearful that winter will find us in the snowy mountains of California.”

Hastings Cutoff

In 1846, however, a dishonest guidebook author named Lansford Hastings was promoting a straighter and a supposedly quicker path that cut through the Wasatch Mountains and across the Salt Lake Desert. There was just one problem: no one had ever traveled this “Hastings Cutoff” with wagons, not even Hastings himself.

At Fort Laramie James Reed ran into an old friend from Illinois by the name of James Clyman, who had just traveled the new route eastwardly with Lansford Hastings. Clyman advised Reed not to take the Hastings Route, stating that the road was barely possible on foot and would be impossible with wagons; also warning him of the great desert and Sierra Nevadas.

Despite the obvious risks and against the warnings of James Clyman, the 20 Donner Party wagons elected to break off from the usual route and gamble on Hastings’ back road. When they reached the head of the canyon,they found a note from Hastings attached to a forked stick. Hastings warned the Donner party that the route ahead was more difficult than he had thought. He asked the emigrants to make camp there and wait until he could return to show them a better way.

Camping in the snow on Sierra Mountains

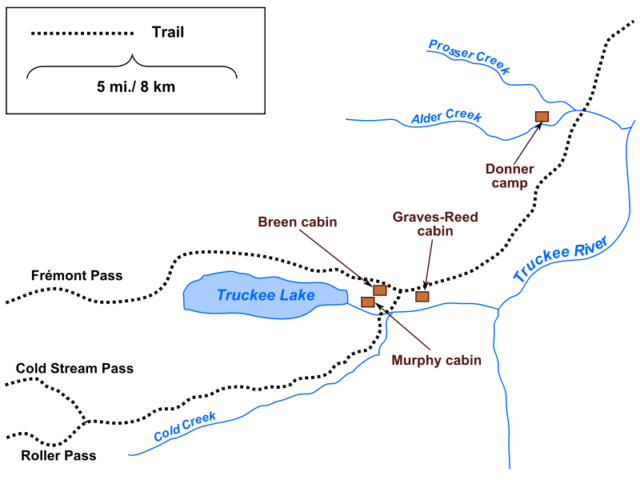

Despite the Hastings Cutoff debacle, most of the Donner Party still managed to reach the slopes of the Sierra Nevada by early November 1846. But for their following tragedies, the culprit was snow. As the Donner Party approached the summit of the Sierra Mountains near what is now Donner Lake (known as Truckee Lake at the time) they found the pass clogged with new-fallen snow up to six feet deep. It was October 28, 1846, and the Sierra snows had started a month earlier than usual. They retreated to the lake twelve miles below where the hapless pioneers were trapped, unable to move forward or back. Shortly before, the Donner family had suffered a broken axle on one of their wagons and fallen behind. Also trapped by the snow, they set up camp at Alder Creek six miles from the main group. Much of the group’s supplies and livestock had already been lost on the trail, and it wasn’t long before the first settlers began to perish from starvation.

Desperation

Life at Truckee Lake was miserable. The cabins were cramped and filthy, and it snowed so much that people were unable to go outdoors for days. Diets soon consisted of oxide, strips of which were boiled to make a “disagreeable” glue-like jelly. Ox and horse bones were boiled repeatedly to make soup, and they became so brittle that they would crumble upon chewing. Sometimes they were softened by being charred and eaten. Emigrants caught and ate mice that strayed into their cabins. Many of the people at Truckee Lake were soon weakened and spent most of their time in bed.

Desperation grew in camp and some reasoned that individuals might succeed in navigating the pass where the wagons could not. On November 12, the storm abated and a small party tried to reach the summit on foot, but found the trek through the soft, deep powder too difficult, and returned that same evening. Over the next week, two more attempts were made by other small parties, but both quickly failed.

On December 16, 1846, more than a month after they became snowbound, 15 of the strongest members of the Donner Party strapped on makeshift snowshoes and tried to walk out of the mountains to find help. After wandering the frozen landscape for several days, they were left starving and on the verge of collapse. The hikers resigned themselves to cannibalism and considered drawing lots for a human sacrifice or even having two of the men square off in a duel. Several members of the party soon died naturally, however, so the survivors roasted and consumed their corpses. The gruesome meat gave them the energy they required, and following a month of walking, seven of the original 15 made it to a ranch in California and helped organize rescue efforts. Historians would later dub their desperate hike “The Forlorn Hope.”

As their supplies dwindled, the Donner emigrants stranded at Truckee Lake resorted to eating increasingly grotesque meals. They slaughtered their pack animals, cooked their dogs, gnawed on leftover bones and even boiled the animal hide roofs of their cabins into a foul paste. Several people died from malnutrition, but the rest managed to subsist on morsels of boiled leather and tree bark until rescue parties arrived in February and March 1847. Not all of the settlers were strong enough to escape, however, and those left behind were forced to cannibalize the frozen corpses of their comrades while waiting for further help. All told, roughly half of the Donner Party’s survivors eventually resorted to eating human flesh.

Rescue

The survived were rescued from the mountains in four relief parties between February and March 1847. In the Donner Party tragedy, two-thirds of the men in the party perished, while two-thirds of the women and children lived. Forty-one individuals died, and forty-six survived. In the end, five had died before reaching the mountains, thirty-five perished either at the mountain camps or trying to cross the mountains, and one died just after reaching the valley. Many of those who survived lost toes to frostbite.

George and Jacob Donner, both of their wives and four of their children all perished. Nearly a dozen families had made up Donner wagon train, but only two—the Reeds and the Breens—managed to arrive in California without suffering a single death.

The story of the Donner tragedy quickly spread across the country. Newspapers printed letters and diaries, and accused the travelers of bad conduct, cannibalism, and even murder. The surviving members had differing viewpoints, biases and recollections so what actually happened was never extremely clear. Some blamed the power hungry Lansford W. Hastings for the tragedy, while others blamed James Reed for not heeding Clyman’s warning about the deadly route.