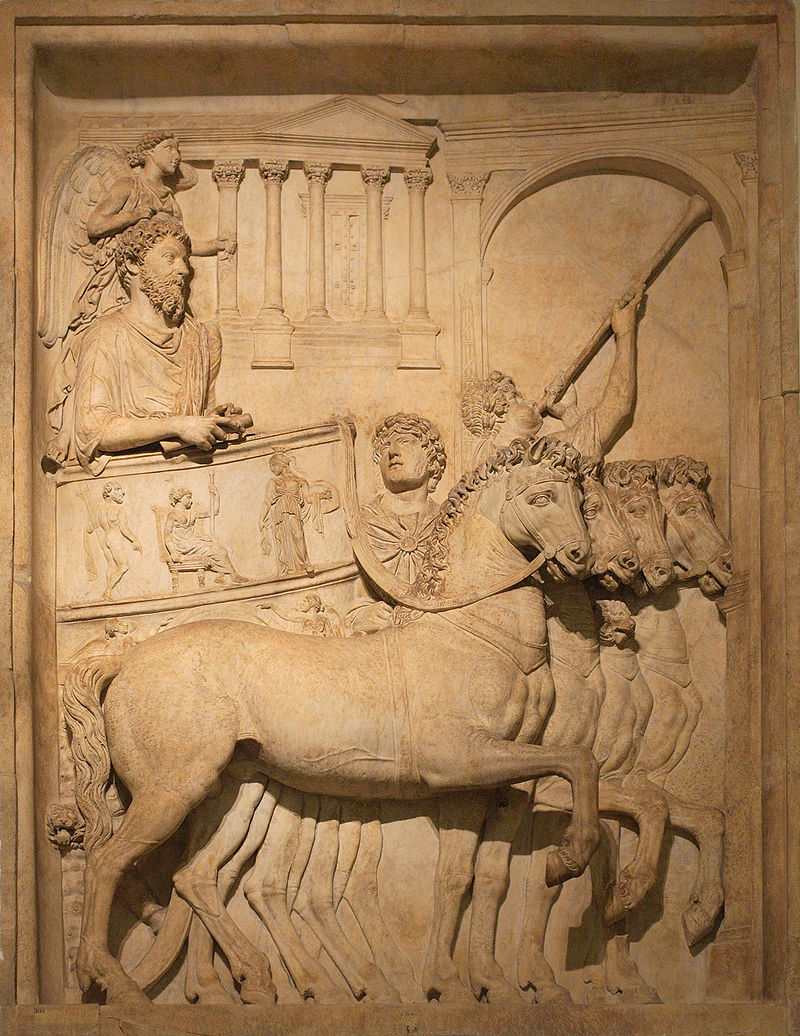

After every major military victory in ancient Rome, a “triumph,” as it was called, was celebrated in Rome. It was a ceremonial procession granted to victorious generals who drove in a chariot drawn by four horses. They would ride through the streets to the temple of Jupiter, on the Capitoline Hill, to offer sacrifice in the temple. When they reached the foot of the Capitoline, some of the leading captives may have been taken off for execution.

The ceremony usually started early in the morning and took up a whole day and sometimes even more than two days. Before the general entered the city at a specific point, the Porta Triumphalis, he would first give a speech praising his legions.

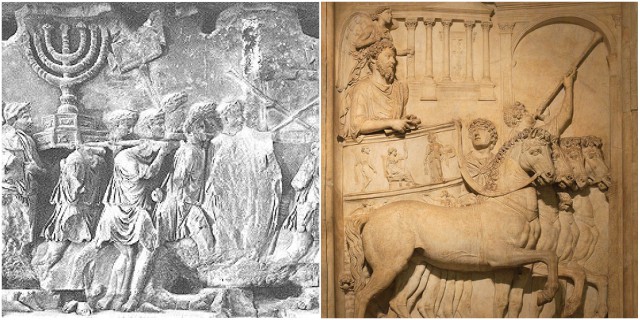

The victorious general who drove throughout the streets of Rome in the chariot, decorated with gold and ivory, was followed by his troops and preceded by his most glamorous prisoners and spoils, taken in war. The triumph for the victorious general offered extraordinary opportunities for self-publicity and therefore popularity with the people of Rome. The victorious general was seen as, in some way, divine, representing the god Jupiter.

Paintings depicting certain episodes of the battle were used in the ceremony. There were also musicians, as well as examples of the exotic plants and animals taken from the conquered country.

The general was dressed in an elaborate red or purple toga and his face was painted red to imitate the red-painted face of the statues of Mars, the god of war or Jupiter – the King of the gods. The red paint was made with vermilion, an opaque orange-red pigment, derived from powdered mineral cinnabar.

One of the most interesting parts of the triumph was that behind the victorious general in the chariot stood a slave, holding a golden crown over his head, and whispering to him throughout the procession, ‘Remember you are mortal’ in the ears of the victorious generals as they were paraded through the streets, reminding him that he is a man even when he is triumphing.

When the procession reached the temple of Jupiter, a bull was sacrificed and offered some of the war-booty in honor of Jupiter. When the ceremony was over, the general was given a musical escort to accompany him back home.

As Mary Beard, the author of The Roman Triumph wrote in her richly illustrated work, “Roman triumphs have provided a model for the celebration of military success for centuries.

More from us: The Decadent 13th Century Caerlaverock Castle is a symbol of the medieval stronghold. …

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our Today In History newsletter!

Through the last two millennia, there has hardly been a monarch, a dynast, or autocrat in the West who has not looked back to Rome for a lesson in how to mark a victory in war to assert his own personal power”.