The scene seems so sweet and innocent: a group of young children, boys and girls, playing outside in the sunshine and fresh air on a fall day, riding bikes, running around, chasing spiders, wrestling, laughing. Someone suggests that one little girl kiss one of the little boys on the cheek, which she did. Perhaps it was a dare. But what it set in motion was a tragedy.

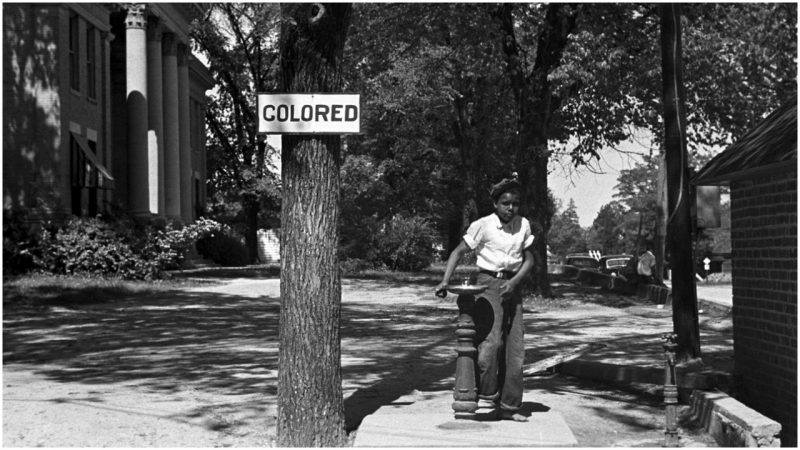

The boys were black and the girl was white, and in the segregated rural South of the 1950s, that spelled trouble. Receiving a peck on the cheek from someone who didn’t share your racial heritage was such a violation of then-customary codes of conduct that the boys would pay a terrible price.

Sissy Marcus, the 6-year-old white girl, skipped to her home in Monroe, North Carolina, on that October day in 1958 and delightedly told her mother about kissing her little friend. Bernice Marcus became enraged. She “washed Sissy’s mouth out with lye, and called the police to report that a black boy had sexually assaulted her daughter,” according to Casting Her Own Shadow: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Shaping of Postwar Liberalism, by Allida M. Black. Armed men allegedly took to the streets to track down the boys themselves.

The two boys, then 9 and 7 years old, were arrested and held in jail for nearly a week without contact with their parents or legal counsel. Police beat them. James Hanover Thompson and David “Fuzzy” Simpson were accused of “molestation”; a juvenile judge declared them guilty and sentenced them to reform school until they reached age 21, according to the Washington Post. Thompson’s and Simpson’s mothers were fired from their jobs as domestics and “threatened,” according to a local newspaper. Thompson’s dog was killed. The Ku Klux Klan burned crosses outside the police station.

“The Kissing Case,” as it came to be known, attracted worldwide attention. People demonstrated in Paris, Rome, and Vienna. This was when the civil rights movement was gathering momentum, about two years before the famous lunch-counter sit-in in Greensboro, 100 miles to the north of Monroe. President Eisenhower and former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, a vigorous champion of civil rights, protested the treatment of the boys and called for clemency.

Brenda Lee Graham, sister of James Thompson, remembered what it was like for her family for NPR’s StoryCorps project, which records conversations and archives them in the Library of Congress for future generations to hear.

“Mom was a nervous wreck. She didn’t sleep,” Brenda told her little brother in their 2011 StoryCorps recording session. “She would be up walking the floors and praying.”

Brenda remembered men burning crosses in the family’s front yard, and her mother having to sweep the porch of bullets in the mornings.

Finally, after the boys had been detained for three months, North Carolina Governor Luther H. Hodges bowed to intense public pressure and allowed the boys to be released, though he insisted to the New York Times that they had been held “for their own protection.”

A commissioner for the North Carolina State Board of Correction and Training had been sent to visit the homes of the boys’ families—who since the incident had moved to Charlotte. Commissioner Blaine M. Madison determined that their family situation was now “such to justify release,” according to a February 14, 1959, New York Times report.

James and Fuzzy were allowed to go home to their families, but they were marked forever by those awful months. As a grownup, James would have trouble keeping a job and would land in jail for robbery. He lives to this day in North Carolina.

“It was like seeing somebody different, that you didn’t even know,” Brenda said in her StoryCorps recording, about her brother’s return home. “He never talked about what he went through there. But ever since then, his mind just hadn’t been the same.”

Related story from us:Claudette Colvin was the first person to resist bus segregation in Alabama

Or as James himself told StoryCorps: “I always sit around and I wonder, if this hadn’t happened to me, you know, what could I have turned out to be? Could I have been a doctor? Could I have went off to some college, or some great school? It just destroyed our life.”