A wedding day and a wedding veil in the classical world was not necessarily about love in the sense of how romance infuses marriages these days. It was more about forging bridges between two families and maintaining economic and social status. However, it is clear from the numerous accounts we have at our disposal that a wedding day was an important event on the calendar in ancient Greece and ancient Rome. And so was the clothing of the bride; her ensemble was worn only once and received as much attention as a wedding dress does nowadays.

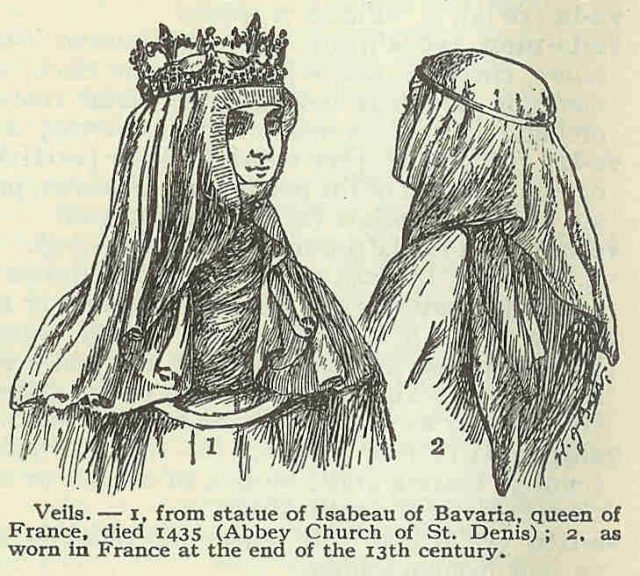

One very intriguing detail of a bride’s clothing in ancient Rome was her veil, which was a necessary part of her wedding day attire. Called a flammeum, it covered the bride’s head, but not her face as is the modern tradition, and was large enough to wrap around her. There are some uncertainties about the flammeum and experts have not agreed on its color, but its purpose seems to be clearer.

Because the word is close to the Latin “flamma,” which means flame, some take this as a hint that the veil of an ancient Roman bride could have been red. But not everyone supports that theory. More accounts say the veil was colored deep yellow; Roman author Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD) likens the flammeum to the color of egg yolk. He also writes: “I understand that yellow was the earliest color to be highly esteemed and was granted as an exclusive privilege to women for their bridal veils.” Other Roman literature indicates that they were dyed with luteum, or luteolin, a yellow dye that is still used today in paints and to dye leather.

Whatever the color, there is a consensus that the veil would make the bride appear as if she were a candle flame. This was purportedly done to ward off evil spirits that might threaten to ruin the special day and all the proceedings. In a pool of theories on the function of the bride’s veil, this seems to be the favorite one: To confuse the spirits.

We might never be entirely sure of the symbolic nature of it, but this tradition with archaic roots established itself as a means of camouflaging the ancient Roman bride from the grip of evil. It would have been similar among ancient Greeks, according to sources.

There are other traditions from those times that we still follow today. As Glamour magazine writes, the bridesmaids wearing matching dresses on the wedding day is a practice dating to Rome. Bridesmaids were allegedly asked to put on the same dress as the bride, to bring good luck for both the bride and groom.

The matching dresses were, again, to befuddle any spirits that might attend the wedding ceremony to curse those entering the life-long union. Among several similar looking dresses in the crowd, the spirits would be unable to recognize who is the bride.

Nevertheless, the massive wedding veil of the bride could have also had more functions, such as preventing her from running away on the big day and assuring she will be safely delivered to take her vow, according to Bustle. Other elements of the bride’s wedding outfit were also recognized for their protective properties, such as the set of jewelry that would adorn her.

Reportedly, underneath the wedding veil, the bride wore a simple white dress, or tunica recta, which was woven in a traditional way. Even the fabric, usually wool, was chosen because people believed this was the “lucky” fabric, again intended to keep away evil. About the bride’s waist a belt of wool would be tied in a complicated Hercules knot (hence “tying the knot”) which was only for her husband to untie.

Many of these precautionary measures were deemed necessary because people believed the bride was in a severed position. Exiting the household where she was born meant leaving behind the protections granted to her by the deities worshiped by her family. Before the ceremony was completed and she joined the household of the groom, the bride was sort of in a limbo, stripped of the gods who can offer her protection in the outside world.

If we look for more traditions that seem to have seeped into the Western world since the Roman days, they exist. Think wedding cakes and ancient Roman wedding guests breaking a loaf of bread over the head of the bride. But this didn’t have to do anything with warding off bad spirits; it was an observation for the sake of the bride’s fertility. Neither are weddings in the month of June anything new. That is connected with the goddess Juno, who presided over martial love and fertility, which is why so many Roman weddings happened in June.