The election of a new pope is a momentous event. The College of Cardinals vote using secret ballots four times a day until a “winner” is declared. The process often takes a few days and, in the past, it has even taken as long as several weeks or months for the College to come to an agreement and a new pope to be elected.

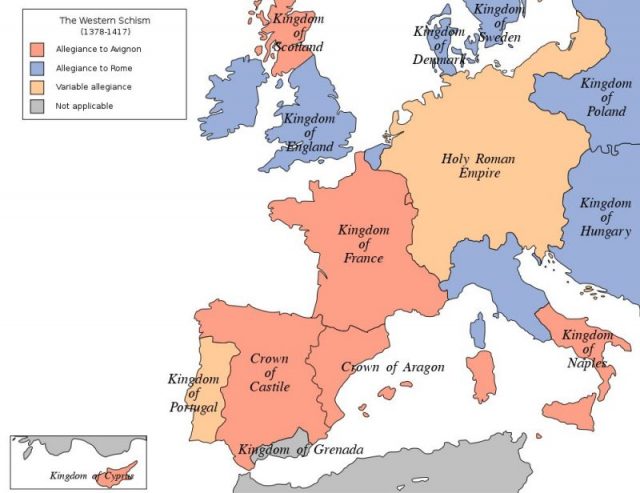

During the late 14th century, this process hit a major hiccup. From 1309 to 1376, the residence of the Pope was in Avignon, France. In total, seven popes lived in Avignon, all French, and therefore all under the influence of the French monarch. But in 1376, Pope Gregory XI left Avignon and returned the papacy to Rome. Unfortunately, he died shortly thereafter, in 1378, and the resulting deterioration of relations between the new pope – Urban VI – and a group of French cardinals resulted in the Papal Schism, also called the Western Schism.

Urban VI was particularly hostile to the French cardinals, who had held great power when the papacy was based in Avignon. His aggression was so intense that he was suspected of being insane, giving rise to questions on the validity of his election as Pope. The French cardinals moved to Anagni, in central Italy, that same year and elected one of their own as Pope Clement VII, declaring that the election of Urban VI was invalid as it was held under fear. Clement VII took his court, and entourage of Cardinals, back to the papal palace in Avignon.

Thus began the second group of Avignon popes, which were seen as illegitimate, and are referred to as antipopes by the Catholic Church (historians of Catholicism today agree in general that Urban VI was the “real” pope, as well as his successors). The last of the Avignon popes, Benedict XIII, lost support in 1398, and fled Avignon in 1403. However, it wasn’t until 1417 that the Council of Constance declared the French conclave to be invalid and elected Pope Martin V. Nevertheless, other claims to the Avignon papacy continued until around 1437.

Secrets of the Medieval Castle.

This election of two–and later three–rival popes had terribly negative effects on the Catholic Church at the time. Followers of the popes were divided nationally, for the most part, with the French siding with Clement VII in Avignon and the English and much of the German empire agreeing with the election of Urban VI. This strongly echoed the political climate of the time–the Hundred Years War between France and England lasted from 1337 to 1453.

Neither pope had a clear edge when it came to power, and neither was willing to relinquish his claim. As a result, the unity of the church was greatly disrupted, causing extensive confusion, conflict of jurisdictions, and, naturally, devastating spiritual angst.

In an attempt to end the schism, a council of cardinals was arranged at Pisa, in 1409, where they elected a third pope–Alexander V, who was succeeded shortly afterwards by John XXIII. However, in an attempt to finally end the Papal Schism, the Council of Constance deposed John XXIII in 1414. It also received the resignation of the Roman pope, Gregory XII, and rejected the claim to the power of the Avignon pope, Benedict XIII. Martin V was elected and became the first papal leader in 40 years to preside over the whole Roman Catholic Church.

The achievement of the Council was tremendous. It ended four decades of disarray and disorder in the church and began a period of expanded authority for the councils. While this authority waned over the years, it never entirely died, and was revived in the Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965. To this day, however, the Catholic Church has never made any official or authoritative proclamation about the various lines of succession, nor the entire period of the Papal Schism.

Patricia Grimshaw is a self-professed museum nerd, with an equal interest in both medieval and military history. She received a BA (Hons) from Queen’s University in Medieval History, and an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and completed a Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto before beginning her museum career. She has lived and traveled all over Canada and Europe.