Piracy is in the eye of the beholder. In the 18th century, there were two types of pirates: The scallywags who fought with and plundered any ship they came across regardless of nationality, and the legal kind, known as privateers.

A privateer would receive a letter of marque from a nation, granting him the legal right to intercept and raid ships belonging to the enemy.

Merchant ships were usually fair game to a privateer, as it would deny the enemy country valuable food and supplies.

While piracy was universally despised by the countries of the world, privateers were able to operate with some level of acceptability, though attitudes towards privateers varied.

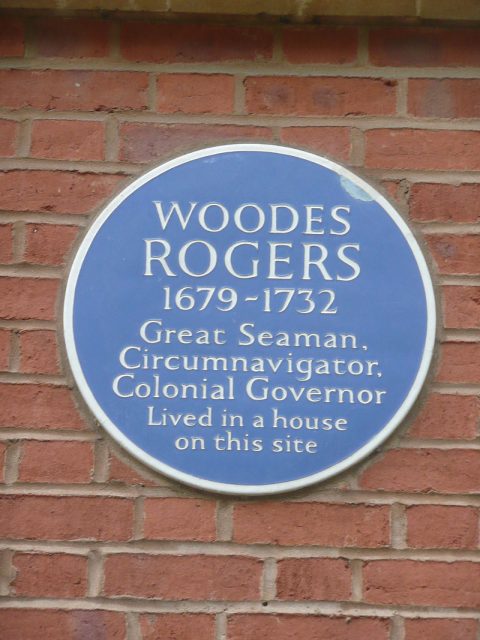

One such privateer was an Englishman by the name of Woodes Rogers, who made for a curious case in privateering.

While most privateers were those of rough cut backgrounds, such as explorers or pirates who were just looking to make a legitimate-ish living, Rogers grew up rather wealthy.

His father had been a very successful merchant captain and had left his business to Woodes Rogers when he passed away in 1706.

As a merchant, it was unlikely that Rogers would take to the art of fighting in naval battles against ships. However, it was piracy that left him with a taste for revenge.

During the course of managing his company, his ships were frequently plagued by the French privateers who were major enemies of England at the time.

As a merchant, his ships would be prime targets and he sustained losses that were costly. With the War of Spanish Succession growing, letters of marque were being issued and Woodes Rogers could have seen privateering as a way of making his money back.

At the insistence of William Dampier, a man who had prior to this been serving as a privateer captain, Rogers would put together a force to sail across the world.

Securing financing from Bristol, where he had been residing, was not difficult, as many merchants had felt the sting of pirates affecting their bottom line. With Dampier as his navigator, Rogers set out in 1708, to seek his fortune.

The journey wasn’t an easy one.

Dampier had neglected to mention the fact that his previous expedition had been a miserable failure because not one but two of his ships had sunk due to his neglect of properly maintaining the hulls.

On top of that, Dampier had also suffered at the hands of several mutinies.

While Rogers was a sailor, he didn’t have quite the presence or strength of character that a salty sea captain did and struggled to keep his crew in line. Some deserted, some rioted and mutinied.

Rogers’s target was the Spanish who were in the Pacific Ocean. By heading across the globe, they would be able to stage attacks against unsuspecting Spanish vessels that normally didn’t have to worry about English ships, since they were so close to home.

Once they made it to the Pacific, they sought out supplies from Juan Fernandez Island.

It would be on that island that they made quite the discovery. A man by the name of Alexander Selkirk had been living on the island, ragged and wearing goatskins. He was not a native but rather had been stranded four years previously.

Selkirk was a Scotsman who had previously abandoned Dampier during an expedition and had been marooned on the island due a dispute with his new captain. Thankful to see Englishmen, Selkirk aided them in gaining supplies and joined them in their expedition.

Much later, Woodes Rogers would write about these exploits and Daniel Defoe would create a tale that may have been inspired by Selkirk, a story known as Robinson Crusoe.

Soon, Rogers’s fleet was attacking Spanish targets, conducting raids against merchant vessels as well as attacking a town on the coast of Ecuador.

Their exploits were modestly successful, although tensions continued to build as the crew did not believe that they were being paid their fair share.

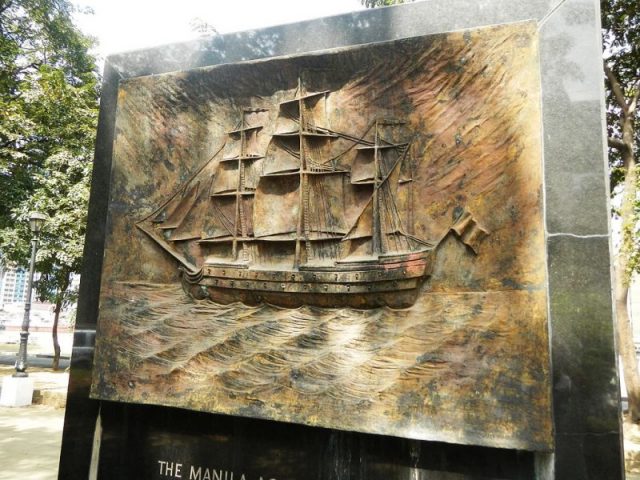

Despite these growing fears of mutiny, Rogers was able to secure a tremendous victory in capturing a Spanish galleon known as the Encarnacion.

This warship had been caught by surprise, as they had not been expecting armed attacks and after a brief fight, they surrendered.

It was during this battle that Woodes Rogers would incur two grievous injuries, the first was that his brother was killed in the battle and the second was that he was shot in the jaw by a musket, which disfigured him.

Regardless of the personal cost, however, they were able to secure the Encarnacion and its cargo.

10 Bizarre Pirate traditions most people don’t know about

The expedition would end shortly after this capture, as the galleon and other ships that had been captured provided them with more than enough plunder. They returned to England in 1711, doubling the investment that had been made.

Yet, while Rogers would be hailed as a national hero for his accomplishments, being the first Englishman to sail across the globe and return with all of his original ships intact as well as his acts against the Spanish, nothing but woe awaited him back home.

His crew, unsatisfied with what they were paid, sued him, forcing him into bankruptcy.

Despite his financial failings, his reputation was secure enough for him to have been granted the commission of the brand-new office of Royal Governor of the Bahamas.

The small islands had been without formal government protection for a long time, making them susceptible to piracy which had been rampant in the region.

Rogers took his appointment seriously and raised a fleet to secure the waters and eradicate the piracy problem, either through diplomacy or violence.

Offering what was known as the King’s Pardon, Rogers allowed any pirate to cease their activity immediately in exchange for a pardon for their crimes. Those who refused were captured and hanged, under Rogers’ jurisdiction.

While his work in the Bahamas was vital for securing, fortifying, and leading to greater economic prosperity, he was never able to get away from his financial problems.

Poorly recognized by the government for his contributions, he ended up in a debtor’s prison, with his old company dissolved and the government refusing to pay debts that he had taken out on their behalf. He even lost the governorship.

Eventually, his debtors took pity upon him and released him, absolving his debts. Rogers was able to petition the King for a pension and his cries were heard.

Related story from us: Meet the real-life pirates of the Caribbean – not a Jack Sparrow among them

Woodes Rogers was granted a pension and was reappointed as Governor of the Bahamas until his death in 1732.

Andrew Pourciaux is a novelist hailing from sunny Sarasota, Florida, where he spends the majority of his time writing and podcasting.