Today, we think of salt as a simple condiment, adding flavor to food and forming a small yet essential part of human nutrition. However, until the 19th century, salt was a critically important global commodity, literally worth its weight in gold.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine, before the advent of refrigeration and modern food preservation technology, salt offered an invaluable way to store and conserve fresh produce, ensuring that the end-of-summer harvest would endure until the following spring. Access to a ready supply of salt could, therefore, be extremely lucrative, as demand for this commodity was widespread and consistent.

Indeed, for one particular Iron Age Celtic community, this “white gold” was the source of vast wealth and prosperity, funding the development of rich culture and leaving behind a tantalizing array of archaeological evidence that continues to inform our understanding of ancient Celtic societies.

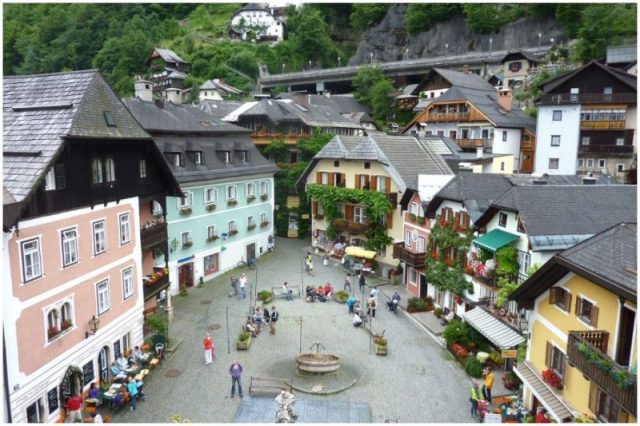

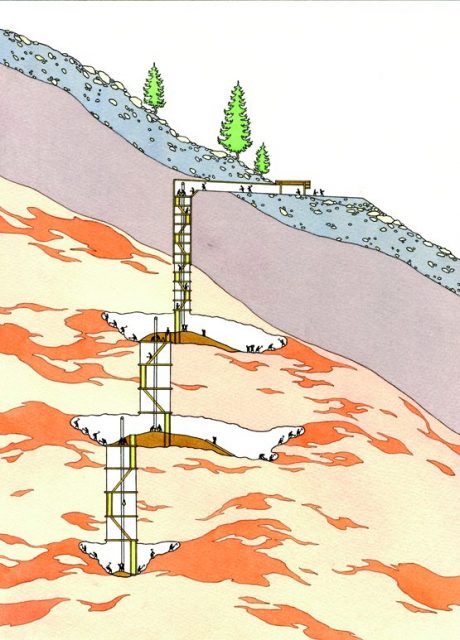

The salt mine of Hallstatt, deep in the Austrian Alps, is thought to be the oldest such mine in existence. This region is the site of vast underground salt deposits, left behind by an ocean that covered the region over 250 million years ago. Today, thousands of years after human beings first began to exploit these deposits, the Hallstatt mine is still in use.

According to The Local, evidence for salt mining at Hallstatt goes back to at least the 5th millennium BC, if not earlier, and it seems to have been in continuous use ever since.

However, perhaps the most notable and fascinating period in the mine’s history occurred between 800 and 450 BC, when a community of Iron Age Celts grew extremely wealthy by mining and exporting the valuable commodity beneath their feet.

Evidence of this rich and culturally profuse society does not come from the mine itself, but rather from a vast cemetery located nearby. Since the 19th century, archaeologists have excavated thousands of graves, some of which contained a wide variety of expensive grave goods usually only associated with high-status individuals.

However, according to the BBC, the people buried with rich grave goods at Hallstatt do not align with our expectations of Celtic society in this period. The vast majority of the skeletons discovered in the cemetery bore the signs of a lifetime of hard physical labor, which would usually denote lower-status individuals, rather than elites.

The residents of Hallstatt, men and women alike, appear to have worked in the salt mines from an early age, undertaking backbreaking work excavating the tunnels and carrying extremely heavy loads. However, these same laborers also grew rich from the profits of their toil, living in such relative prosperity that they were able to be buried with valuable grave goods.

According to the BBC, the diversity of artifacts found at Hallstatt also attests to a wide-ranging system of trade. The salt miners exported salt across Central Europe and south to the Mediterranean, and in return, imported goods and artifacts from thousands of miles away. Finds include ceramics from southern Italy and Greece, and ivory sword handles from as far away as Africa.

Reminders of this important period in the mine’s history may also be found in the ancient tunnels made by the Hallstatt Celts. These tunnels are littered with the remains of tapers and torches that were once used to light the way for the miners who worked in them.

In addition, archaeologists have even discovered feces dating from the Iron Age, perfectly preserved by the salt of the mine itself. This ancient excrement is providing a fertile new source of investigation, providing information about the diet and health of the people who lived and worked at Hallstatt, and their connections with other groups nearby.

Hallstatt was named as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997, and today is an important area for archaeological and historical work. Recently, considerable work has been undertaken on the most ancient parts of the mine, in order to prevent collapse and to ensure that the site remains protected.

Read another story from us: The Magical Underground City Carved Entirely out of Salt Rock

Today, Hallstatt’s white gold continues to be a source of capital, despite the decline in importance of salt as a global commodity. Around 250,000 tons of salt are excavated from Hallstatt every year, suggesting that this is one ancient site that looks set to continue generating wealth for many more years to come.