“Damascus steel”, as it became known, achieved an almost mythical status back in Europe, as the accounts of pilgrims and Crusaders filtered back to their homelands. Blades forged with Damascus steel were said to be flexible enough to bend from the hilt, strong enough to cleave a man in two, and sharp enough to — according to the popular myth of a meeting between the Crusader king Richard the Lionheart of England meeting the Sultan of Egypt and Syria, Saladin — cut through a silk cloth as it fluttered through the air.

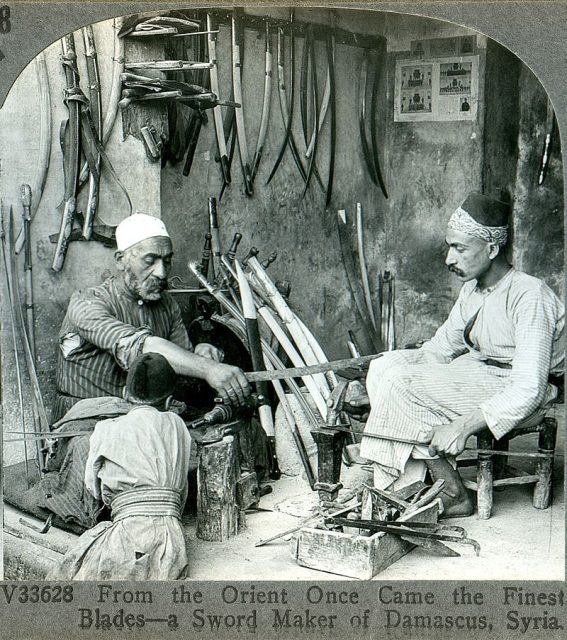

There’s no significant link between the city of Damascus, the capital of modern Syria, and these blades of renown, simply that Damascus was a major production center in the Medieval Muslim arms industry and known even in Europe for its work with steel more generally.

The great city was also a prolific producer of textiles too, and from Damascus, we get the word “Damask” from the elegantly embroidered pattern, not dissimilar to the distinctive oil-in-water pattern of Damascus steel. Either or both of these explanations could be behind the name.

In Europe, weapons were traditionally forged through pattern-welding, in which smaller pieces of iron and steel were twisted together which left a pattern in the surface similar to Damascus steel at first glance, or by using a larger piece of steel in its entirety — the latter replacing the brittle and unreliable former method from the 11th century as metalworkers became more adept at forging larger pieces of steel.

Damascus steel weapons were first believed to have been forged in 500 AD (over a century before Islam arrived in the region) from high-carbon steel called wootz. This was manufactured in a process known in India since approximately 350 BC, and perhaps beginning life in China even earlier than that if some Arab sources were to be believed.

The process was cyclical, iron was mined and exported in North Africa, then exported to India where metalworkers melted it down with carbonaceous (high-carbon) materials such as charcoal or rice husks in sealed crucibles over a period of several days until it became a homogenous mass.

Related Video: Beautiful and Mysterious Viking Treasures

The bubbling liquid would be slowly and steadily cooled into a single, uniform block of wootz with no imperfections. This block of wootz — which perhaps comes from the Indian word ‘ukku”, meaning “melt” or “dissolve” — was then exported to the great cities of Persia, North Africa, Central Asia, and the Levant to be worked into swords and daggers.

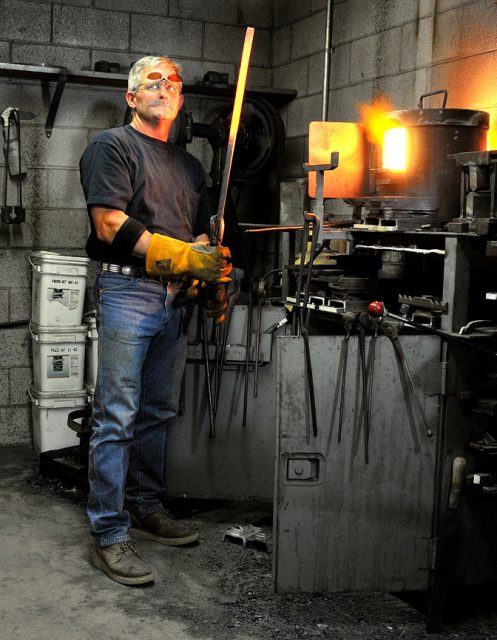

The higher the carbon content of the steel, the lower the temperature it would melt at, and this produced its own difficulties. If the temperature was too great, the blade would shatter like glass under the blacksmith’s hammer, and if it was too low it wouldn’t melt at all. Maintaining the correct temperature over a long period of time, with only instinct and experience to guide you, was difficult work, but it was worth it.

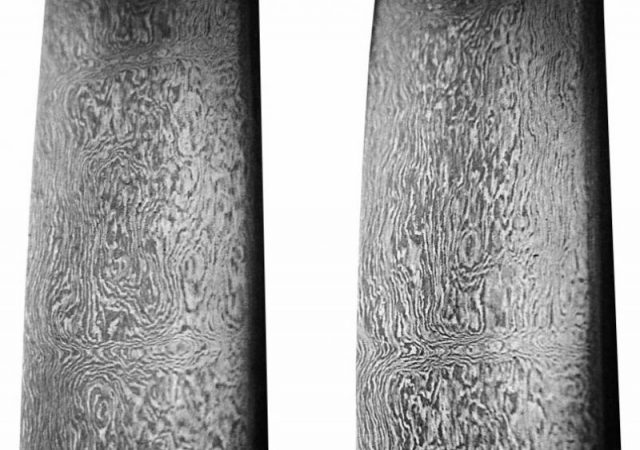

In the lower temperature, the hardened carbide crystals left on the surface of the wootz block by the mold would break. What was left was a sharper edge that couldn’t be easily dulled through use and the signature flowing pattern (embellished with careful etching by the weaponsmiths) that marked each Damascus blade out to its owner as something special, and to its foes as an object of mortal terror.

Without knowing the process which produced Damascus steel, Europeans developed more sophisticated pattern welding techniques which resulted in those similar flowing patterns on the surface and were more durable than the earlier experiments

Incorrectly, for much of history European smiths and metallurgists believed that Damascus steel was a style of blade and not a process by which stronger and sharper weapons could be crafted. This, amongst other things, has led to a number of misleading accounts and museum exhibits which are often referred to today as “false Damascus” or “welded Damascus”. They may look pretty, but they’re not the real thing.

The practice of forging Damascus blades died out in the 18th century, although metallurgists in Great Britain and Russia made repeated efforts to replicate the formula as their domains expanded into areas of their traditional use.

At the Imperial court in St. Petersburg, it became fashionable for aristocratic cavalry officers looking to make a statement to acquire Damascus steel sabers from the Central Asian fringes of the Russian Empire, areas of Mulsim majority that had once been firmly part of the Arab, Turkish and Persian worlds.

What confounded European scientists and smiths, was that the more carbon that is present in steel, the more likely it is to shatter on impact with another sword. The exact reason for Damascus steel’s incredible durability and flexibility proved impossible to duplicate or reverse engineer.

All sorts of reasons are given for the decline in the manufacture of Damascus steel, from the collapse of traditional trade routes into Syria to British suppression of metal exports as they increased their grip over India, but the explanation is most likely the simplest. By the 16th century, gunpowder was rapidly reshaping the European battlefield. Musketeers were outnumbering pike infantry, and the use of cavalry was being reduced in the face of both ranks of smoking muskets and tightly-packed ranks of infantry with bayonets.

Though the Ottoman Empire, which dominated the Middle East, the Balkans, and North Africa until the end of the 19th century, remained stubbornly resistant to military reform for far longer than was strategically healthy (and paid the price in a number of battles with Russia), land reforms had weakened the landowning Sipahis. In earlier centuries, the Sipahis used the profits from their estates to buy weapons, equipment, and auxiliaries like feudal knights had in Medieval Europe. Not only were they now penniless, but they were also obsolete.

Cavalry duties in the Ottoman army increasingly fell to troops of mercenaries, and eventually, it became abundantly clear to even the arch-traditionalists that a musket was cheaper than a horse and more effective in the modern battlefield.

Through the combined effect of the declining importance of sword generally, the move of metalworkers and smiths towards casting cannons and other artillery pieces, and the decline of the wealthy warrior class who might once have been the primary customers for such elaborate, painstakingly crafted weapons, it’s easy to see how the craft faded and then vanished from view.

In 2006, a team from the University of Dresden announced that they had discovered the secret of wootz — carbon nanotubes. The researchers from the University of Dresden analyzed a 17th century blade created by the legendary blacksmith Assad Ullah, which came from the collection of the Berne Historica Museum, Switzerland. They dissolved part of the blade in hydrochloric acid and studied it under an electron microscope. What they found would have been inconceivable to the sword’s creator: the steel was packed with carbon nanotubes (CNTs), each one scarcely larger than half a nanometer.

Carbon nanotubes are cylinders made of hexagonally-arranged carbon atoms. Strong and flexible, CNTs are used in everything from golf clubs to aircraft parts and have enormous potential in medical science as material for implants or scaffolding for the healing of damaged tissue.

While we know how Damascus steel works, how Medieval and Early Modern smiths induced these CNTs remains a mystery. Researchers suspect that the answers can be found in the trace metals found in the wootz, which during the extended process of heating and cooling would have become segregated in the semi-solid wootz like a layer of Irish Cream in a shot glass, a perfect mirror of the flowing lines in a finished blade of Damascus steel.

There, these isolated impurities could have acted as a catalyst for the chemical process which forms nanotubes along the same elegant Damask patterns. This introduces another possible reason for the decline of wootz: Without knowing the precise combination of minerals present in their iron ore, smiths and metallurgists would have been unable to replicate their incredible feats once the original iron mines were scraped clean of their bounty.