In a practical example of camaraderie and heroism, a Second World War pilot saved the lives of his comrades by stepping out of a Wellington bomber at 10,000 feet to extinguish a fire on the wing of the plane and then safely getting back. Co-pilot Sgt James Ward secured the Victoria Cross for his heroism and won the hearts of the friends and their families along with millions back home. Ward instructed his pilot, Widdowson, to keep the plane steady while Ward draped canvas cover over the raging fire. After the fire was extinguished, Widdowson pulled Ward safely back into the bomber.

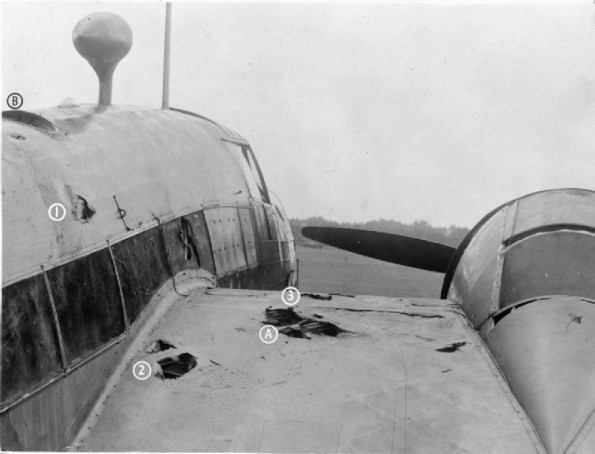

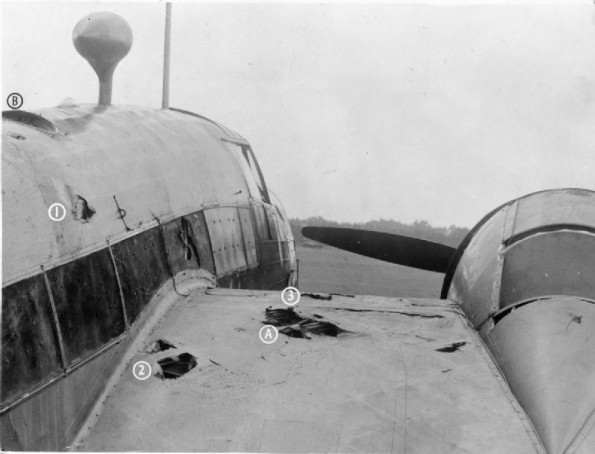

Co-pilot Sergeant James did not realize at the time the magnitude of his actions when he literally defied death by fighting a 100mph slipstream by stepping out and crawling along the wing of the Wellington, only protected by the length of rope held by the pilot of the bomber. Ward’s friend and pilot of the Wellington, Squadron Leader Widdowson, performed the equally remarkable job by keeping the burning bomber steady while with one hand holding the rope attached to the buckle of his co-pilot Ward, who put his life literally in the line of fire to save his fellow soldiers. After subduing the fire eating the wing of the plane, Ward was pulled back into the plane by his fellow members of the crew, who were instructed earlier by Widdowson to prepare for a bailout as he saw the situation spiral out of hand. After Ward had saved the plane, Widdowson managed to safely land the battered and burnt out plane back at its base in Suffolk, where the bomber was only stopped from going off the runway by a barbed wire fence at the end of the strip.

The night of July 7, 1941, wasn’t particularly different from any other bombing ‘sortie’ for the crew of the Vickers Wellington. The bomber delivered the payload to the target military installation in Munster, and after patrolling above the city for a few minutes, decided to head back to base. While the bomber was flying over Zuider Zee at an altitude of 13,000ft, it was stealthily attacked by a German ME110 from beneath, and in a matter of seconds splinters hit the underbelly and wing of the plane. The rear gunner had quickly spotted the attacker and quickly unleashed a barrage of gunfire towards it, blasting it out of the sky; however, pilot and co-pilot had no means of knowing, as communications had been knocked out by this point.

Soon after realizing that they were attacked, the pilot quickly nose-dived the bomber to avoid another burst of bullets from the ME110. The threat was gone, but not before causing considerable damage to the landing gears and the wing of the aircraft, which seemed as if it was going to catch fire any minute. The quick stream of petrol from the engine quickly made the little fire into a blaze which threatened to destroy the entire wing. Seeing the ferocity of the situation, the pilot instructed the crew to put on their parachutes and prepare to bail out, as there was no way they could control the fire. Without landing gear, and with one wing and the whole hydraulics sytem in a critical condition, there was no way the bomber could safely land anywhere.

However, the co-pilot James Ward had other plans. He asked his crew members to help him bore a hole on the side of the fuselage and decided to head out to put out the fire. Previously, they had tried everything they could to control the flames: at one stage, they even threw coffee from their flasks, which only wet the fabric around the fire and didn’t help at all. Ward attached an ordinary rope to his waist and headed out through the hole in the fuselage to the wing by crawling and constantly fighting the strong winds both from the atmosphere and the plane engines. One slight slip meant certain death for Ward, but as he wrote in his account later, he did not fear death as he was out on the wing. He simply thought of the task at hand and worked towards it. Ward did manage to extinguish the fire after some effort and then slowly crawled back into the plane. The pilot decided to head for the English coast, but just before they entered English airspace the fire flared up again. However, to the immense relief of the crew, the fire quickly burned out by itself.