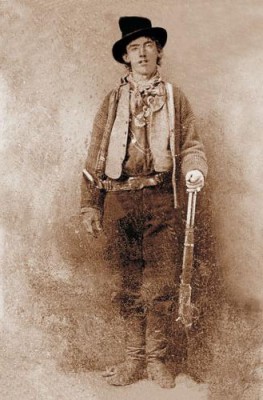

A photograph of American cowboy, Billy the Kid, is being put up for sale and is expected to fetch more than $5 million. The photograph is one of only two believed to still be in existence and was bought by the seller at a junk shop in California five years ago by a Wild West fan.

The photograph is tintype and shows Billy the Kid playing croquet in New Mexico in around 1878. He is accompanied by his gang members, who were known as the Lincoln County Regulators. The photograph has been assessed and identified by experts in the field, with analysis taking more than one year to show its provenance and authenticity. They even visited the site of the photograph in New Mexico to verify it was there in the late 1800s.

The experts were at first quite sceptical that the photograph was real when they first saw it. A photograph of Billy the Kid is a rarity that many Wild West fans would pay a lot of money to own. (Mail Online)

It is around 10cms x 13cms, and upon close inspection a smile can be seen on Billy the Kid’s face as he rests and leans on his croquet mallet. He is wearing a smaller, shorter version of Lincoln’s top hat. In the background is a wooden hut along with a woman and a baby, and a small group of children. The other authentic Billy the Kid photograph in existence is one taken in around 1880. It was put up for sale in 2010 and sold for around $2.3 million.

Henry McCarty (September 17, 1859 – July 14, 1881), better known under the pseudonyms of Billy the Kid and William H. Bonney, was a 19th-century gunman who participated in the Lincoln County War and became a frontier outlaw in the American Old West. According to legend, he killed twenty-one men, but it is now generally believed that he killed eight, with the first on August 17, 1877.

McCarty was 5 ft 8 in (173 cm) tall with blue eyes, blond or dirty blond hair, and a smooth complexion. He was described as being friendly and personable at times, and as lithe as a cat. Contemporaries described him as a “neat” dresser who favored an “unadorned Mexican sombrero”. These qualities, along with his cunning and celebrated skill with firearms, contributed to his paradoxical image as both a notorious outlaw and a folk hero.

He was relatively unknown during most of his lifetime, but was catapulted into legend in 1881 when New Mexico’s governor Lew Wallace placed a price on his head. In addition, the Las Vegas Gazette (Las Vegas, New Mexico) and the New York Sun carried stories about his exploits.

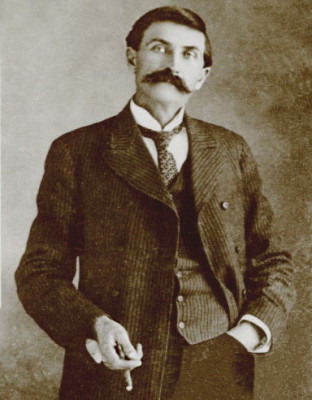

McCarty became acquainted with an ambitious local bartender and former buffalo hunter named Pat Garrett. Popular accounts often depict McCarty and Garrett as “bosom buddies”, but there is no evidence that they were actual friends. Garrett was elected as sheriff of Lincoln County in November 1880, running on a pledge to rid the area of rustlers. In early December, he assembled a posse and set out to arrest McCarty, by that time known almost exclusively as “Billy the Kid.” The Kid carried a $500 bounty on his head that had been authorized by governor Lew Wallace.

Garrett’s posse fared well, and his men closed in quickly. On December 19, McCarty barely escaped a midnight ambush in Fort Sumner, which left gang member Tom O’Folliard dead. On December 23, the Kid was tracked to an abandoned stone building in a remote location known as “Stinking Springs” (near present-day Taiban, New Mexico). Garrett’s posse surrounded the building while McCarty and his gang were asleep inside, and waited for sunrise. The next morning, a cattle rustler named Charlie Bowdre stepped outside to feed his horse. He was mistaken for McCarty and was shot down by the posse.

Soon afterwards, somebody from within the building reached for the horse’s halter rope, but Garrett shot and killed the horse, whose body blocked the building’s only exit. The lawmen then began to cook breakfast over an open fire, and Garrett and McCarty engaged in a friendly exchange. Garrett invited McCarty outside to eat, and McCarty invited Garrett to “go to hell.” Realizing that they had no hope of escape, the besieged and hungry outlaws finally surrendered and were allowed to join in the meal.

The Kid was transported from Fort Sumner to Las Vegas, where he gave an interview to a reporter from the Las Vegas Gazette. Next, the prisoner was transferred to Santa Fe, where he sent four separate letters over the next three months to Governor Wallace seeking clemency. Wallace refused to intervene, and the Kid’s trial was held in April 1881 in Mesilla. The Kid was found guilty on April 9 of the murder of Sheriff Brady, after two days of testimony, the only conviction ever secured against any of the combatants in the Lincoln County War. On April 13, he was sentenced by Judge Warren Bristol to hang, with his execution scheduled for May 13.

The Kid was removed to Lincoln, where he was held under guard on the top floor of the town courthouse by two of Garrett’s deputies, Bob Olinger and James Bell. The Kid killed both guards and escaped on April 28, while Garrett was out of town.

Deputy James Bell reportedly showed the Kid respect and “never, by word or action, did he betray his prejudice if it existed”. Deputy Olinger reportedly treated the Kid badly. Olinger’s favorite weapon and tool of choice when tormenting the Kid was his double-barreled shotgun. He had loaded it with buckshot and was overconfident in his abilities as a guard. On April 28, 1881, Olinger left the prison for lunch, leaving his shotgun in Bell’s custody. The Kid got his hands on a gun somehow and shot Bell, fatally wounding him. It is not clear how the gun came into the Kid’s possession, though various theories have been suggested. The Kid himself later claimed that he never wanted to kill Bell, but the other man stood in the way of his escape.

The second guard was across the street with some other prisoners, and the Kid waited at the upstairs window for him to respond to the gunshot and come to Bell’s aid. As Olinger came running into view, the Kid leveled the shotgun at him, called out “Hello Bob!”, and shot him dead. The site of these killings is preserved in Lincoln County with the hole in the wall on display where Bell was shot, as well as a plaque where Olinger was gunned down. His escape was delayed for an hour while he worked himself free of his leg irons with an axe. Then he mounted a horse and rode out of town, reportedly singing. The horse returned two days later.

Death

Sheriff Pat Garrett responded to rumors that McCarty was lurking in the vicinity of Fort Sumner almost three months after his escape. Garrett and two deputies set out on July 14, 1881 to question one of the town’s residents, a friend of McCarty’s named Pete Maxwell (son of land baron Lucien Maxwell). Close to midnight, Garrett and Maxwell sat talking in Maxwell’s darkened bedroom when McCarty unexpectedly entered the room.

There are at least two versions of what happened next. One version suggests that, as the Kid entered, he failed to recognize Garrett in the poor light. He drew his revolver and backed away, asking “¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?” (Spanish for “Who is it? Who is it?”). Recognizing McCarty’s voice, Garrett drew his own revolver and fired twice, the first bullet striking McCarty in the chest just above his heart, although the second one missed and struck the mantel behind him. McCarty fell to the floor, gasped for a minute, and died.

In the second version, McCarty entered carrying a knife, evidently heading for a kitchen area. He noticed someone in the darkness, and uttered the words, “¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?” at which point he was shot and killed. The popularity of the first story persists and portrays Garrett in a better light, although some historians contend that the second version is probably the accurate one.

Garrett allowed the Kid’s friends to take his body across the plaza to the carpenter’s shop to give him a wake. The next morning, Justice of the Peace Milnor Rudulph viewed the body and made out the death certificate, but Garrett rejected the first one and demanded that another one be written more in his favor. The Kid’s body was then prepared for burial, and was buried at noon at the Fort Sumner cemetery between O’Folliard and Bowdre.

In his book Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life, Robert Utley tells the story of Pat Garrett’s book effort. In the weeks following the Kid’s death, Garrett felt the need to tell his side of the story. Many people had begun to talk about the unfairness of the encounter, so Garrett called upon his friend Marshall Ashmun (Ash) Upson to ghostwrite a book with him. Upson was a roving journalist who had a gift for graphic prose. Their collaboration led to a book entitled The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid which was first published in April 1882. The book originally sold few copies, but it eventually proved to be an important reference for historians who later wrote about the Kid’s life.