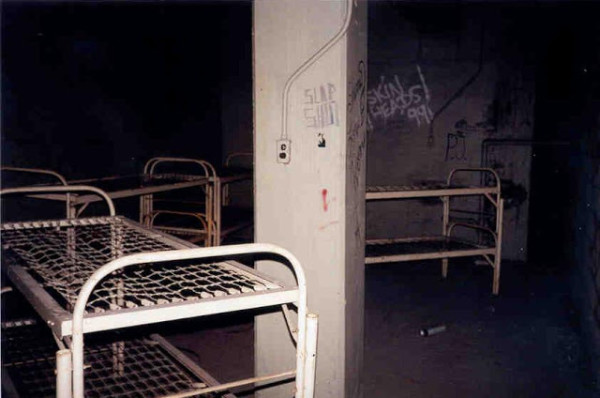

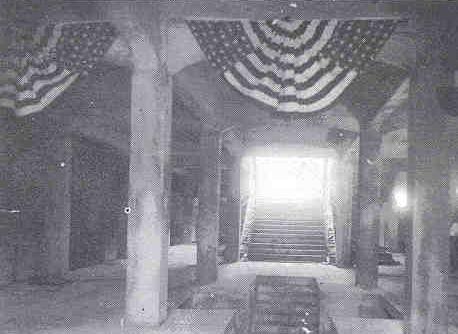

It’s one of the busiest streets in town, Central Parkway, but just beneath the surface is one of the most secret places in the city – the unfinished Cincinnati subway. There are no rails, no buses, no scheduled service of any kind, just a half-mile of concrete subway tile and mosaic artwork few people know even exists. That subway tunnel has been there, intact since it was abandoned since about 1928, attracting more rust, than riders.

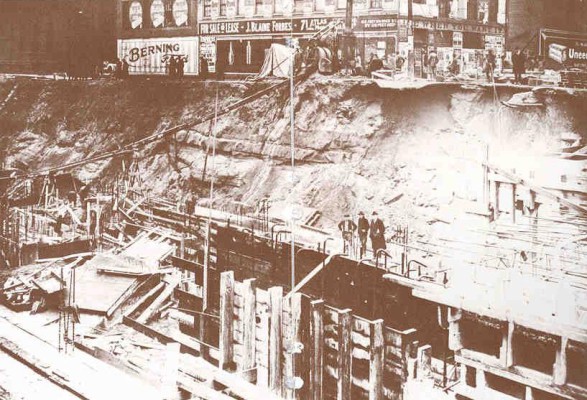

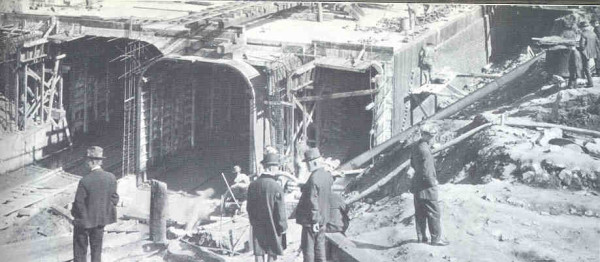

The subway was built by the City of Cincinnati between 1920 and 1925. Seven miles of the line were constructed in some way, from downtown Cincinnati beneath Central Parkway, and on up to Norwood. Construction was stopped in 1925 when the city ran out of money to continue. The project ran extremely over budget as a result of inflation. The bonds taken out to provide the funding for the project were taken in 1916, shortly before the US entered WWI. As a result of the war effort, construction was put on hold until 1920. By the end of the war, inflation had made the $6 million worth of bonds worth just a fraction of what they had been 4 years prior, and the budget for the project had more than doubled due to increased supply and labor costs.

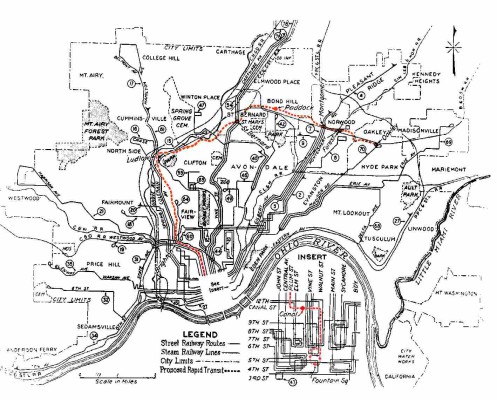

The projected route of the rail system was as follows:

The original plans for the transit loop began at 4th and Walnut Street near Fountain Square. Now, the old subway system was going to run north along Walnut Street to the canal, and then when it hit the canal, it was going to follow under Central Parkway up through the Mohawk and Brighton areas to Ludlow Avenue. The subway was constructed only to a point just north of the Western Hills Viaduct, with a short tunnel under Hopple Street that was never completed. The line would have then run above ground in the canal along a section which is now Interstate 75, to Saint Bernard. The loop would then tunnel under a section of Saint Bernard and eastward in the open on private rights-of-way to a short tunnel under Montgomery Road in Norwood. It then would have run along a high retaining wall to another subway tunnel under Harris Avenue. Then it goes above ground again through the Norwood Waterworks Park, southward along Beech Street by the United States Playing Card Company to Duck Creek Road. The rest of the loop was never constructed but it would have run along a stretch of Interstate 71 to Madison Road. A tunnel would run under the Owl’s Nest Park, through the hills to Columbia Parkway and along the Parkway on an elevated railway into the downtown area back to Fountain Square.

Once it became apparent that the original rapid transit plan had failed, political infighting in City Hall stalled any new progress, and any hope of raising the money to complete the subway was further delayed with the stock market crash of 1929.

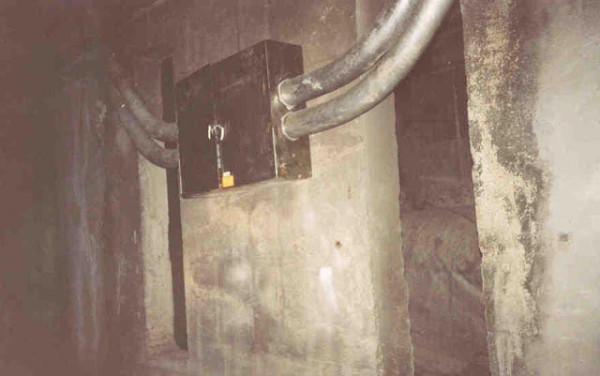

The uncompleted subway tunnels and stations have been described as “strikingly well preserved” and “in good shape.” This is partially credited to the original construction quality, and partially because Cincinnati must use tax revenues to maintain the tunnel because Central Parkway is situated on top of it.

In 2008 it was estimated that it would cost $2.6 million for current maintenance on the tunnels, $19 million to fill the tunnels with dirt, and $100.5 million to revive the tunnels for modern subway use. Relocating the 52-inch (1.3 m) water main would cost $14 million.

The subway route was designed to run parallel to the interstate, which would make for a quick and stress-free commute. If the rapid transit project would have been completed on time, as it was originally planned, residents would see a tremendous improvement economically and environmentally for Cincinnati. Cincinnati’s Abandoned Subway is a legend of innovation, politics, and failure. More importantly, the unfinished rapid transit system is a valuable lesson of how present decisions impact the lifestyles of the future generations.