The earliest reference to Dublin is sometimes said to be seen in the writings of Claudius Ptolemaeus (Ptolemy), the Egyptian-Greek astronomer and cartographer, around the year 140, who refers to a settlement called Eblana. This would seem to give Dublin a just claim to nearly two thousand years of antiquity, as the settlement must have existed a considerable time before Ptolemy became aware of it. Recently, however, doubt has been cast on the identification of Eblana with Dublin, and the similarity of the two names is now thought to be coincidental.

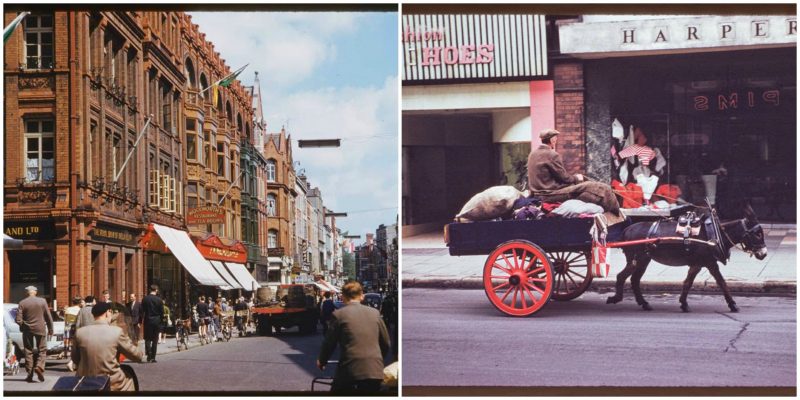

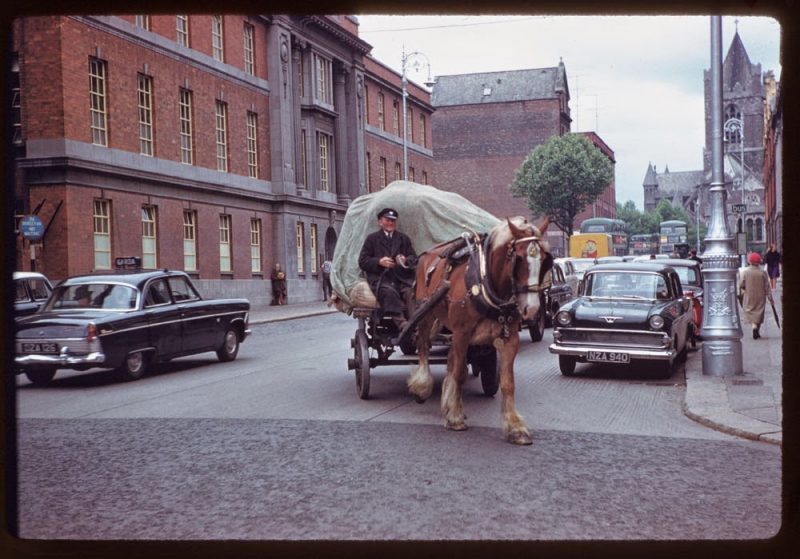

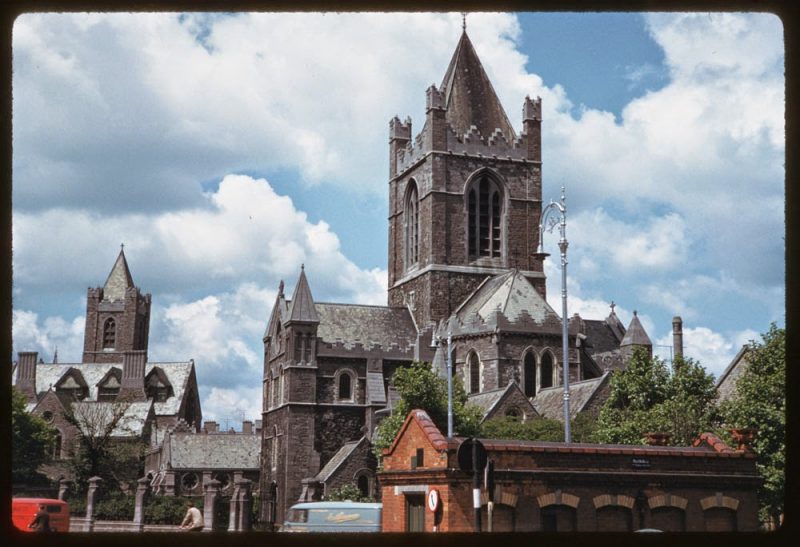

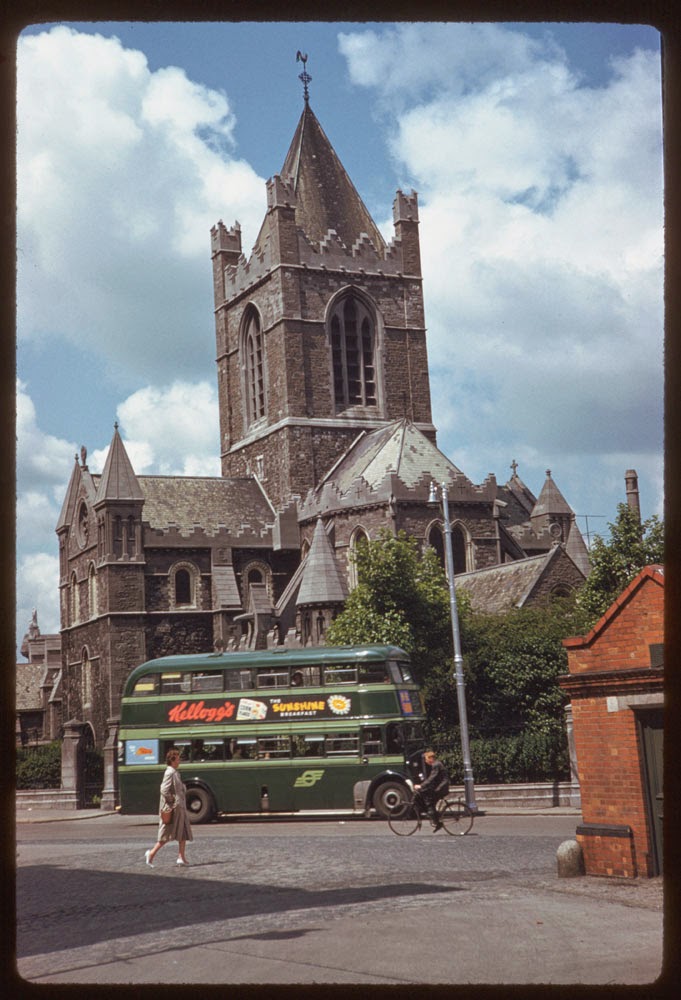

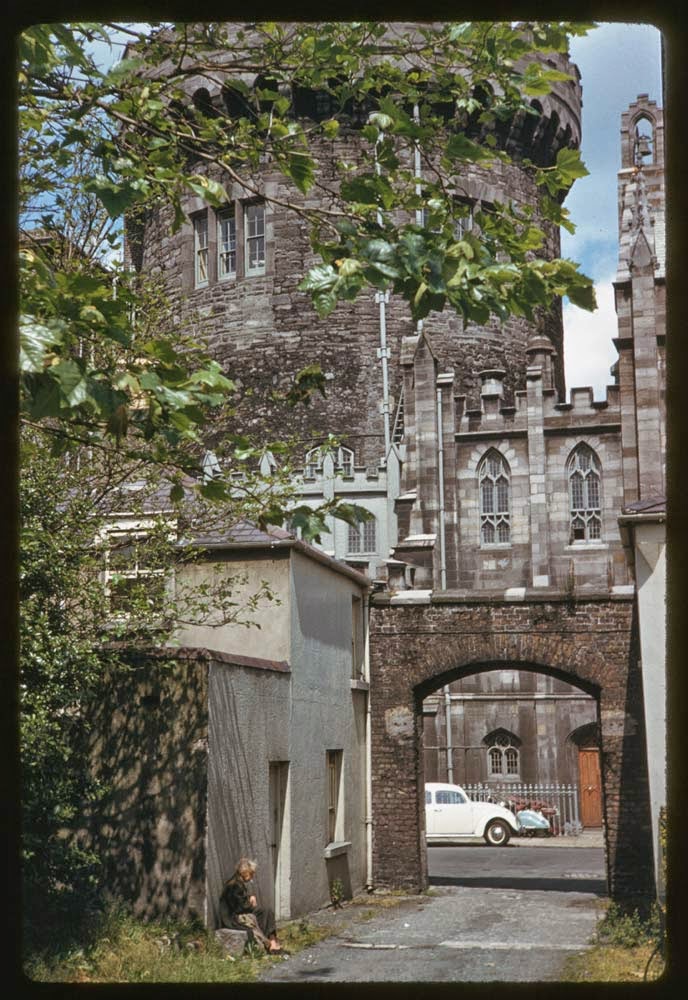

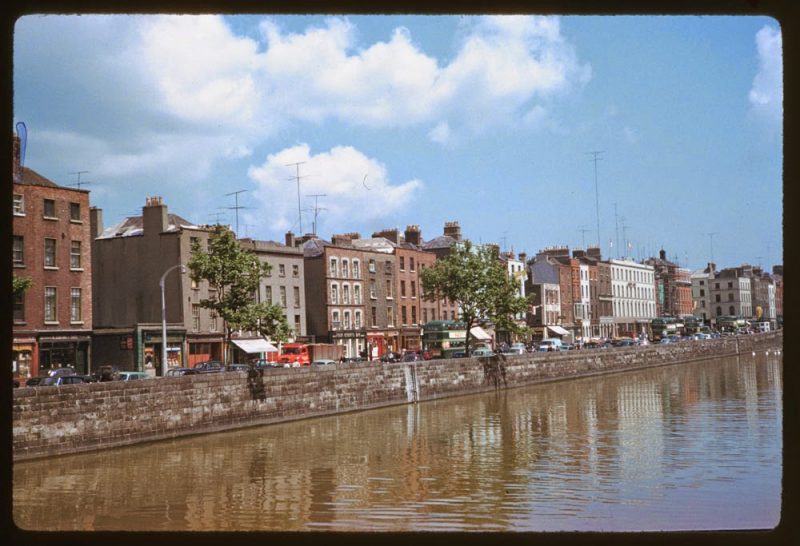

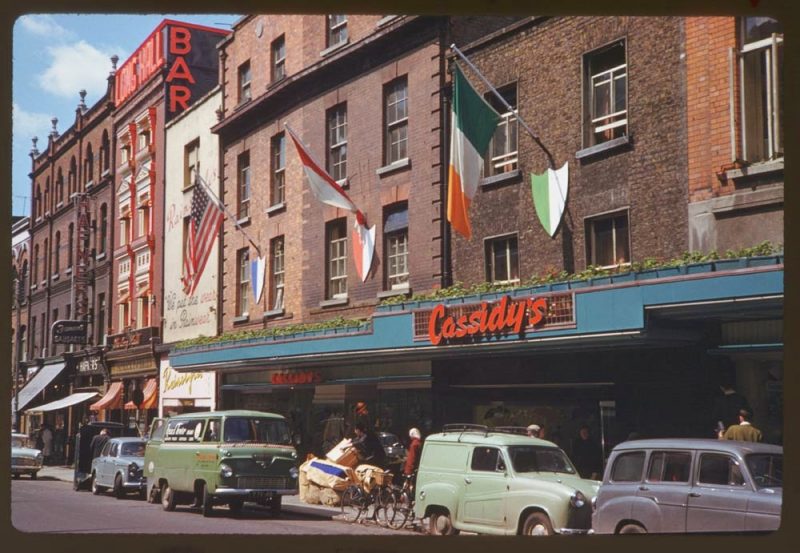

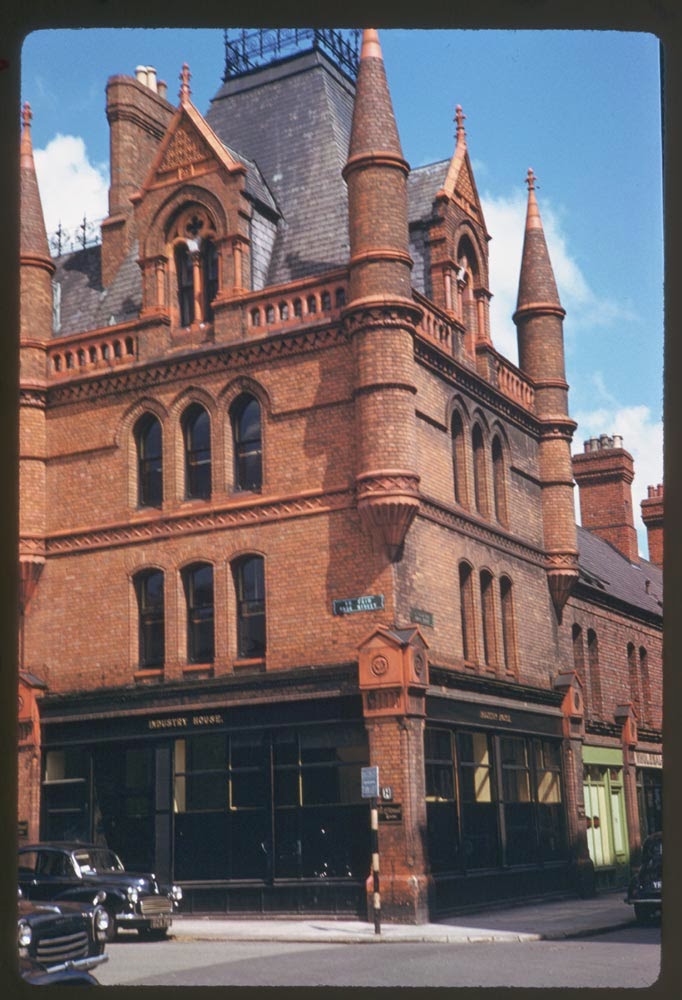

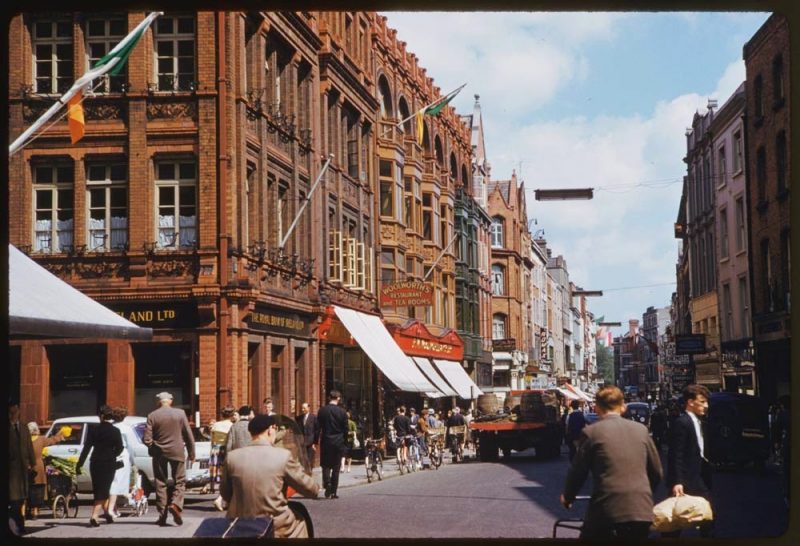

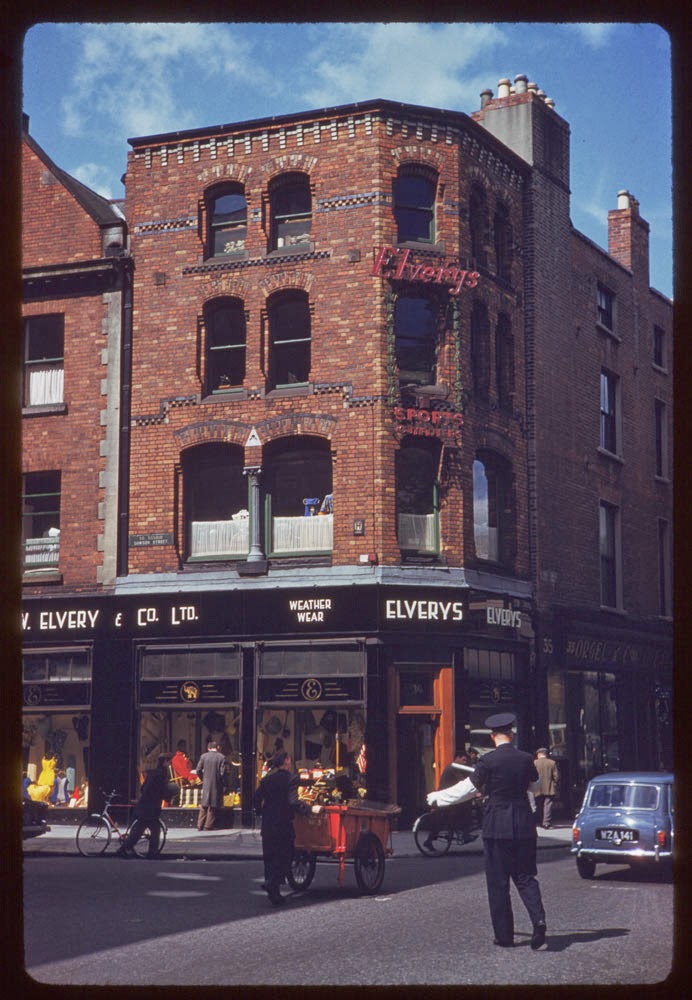

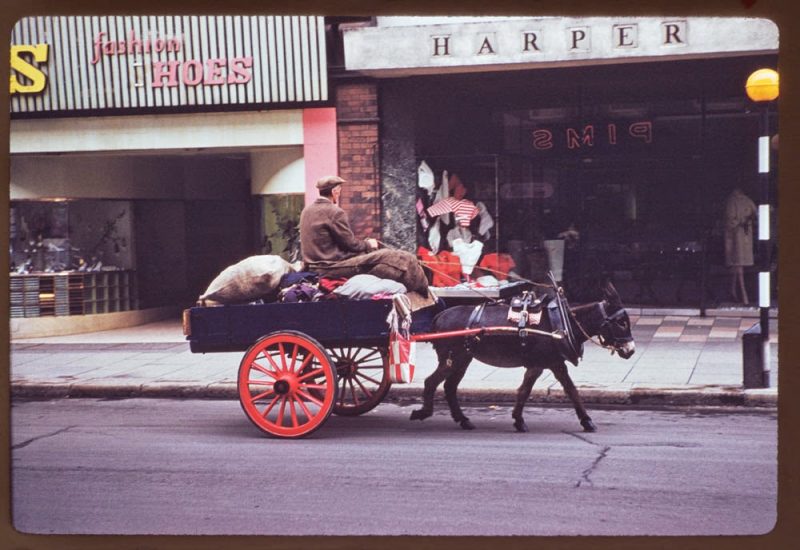

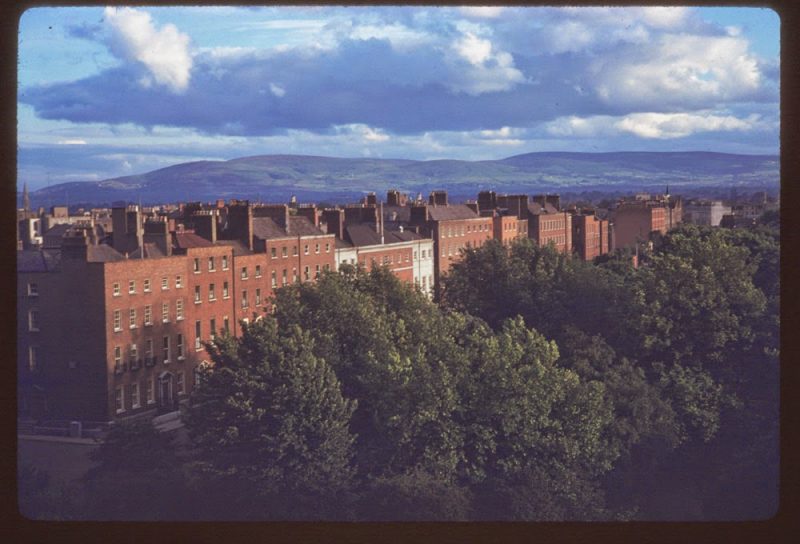

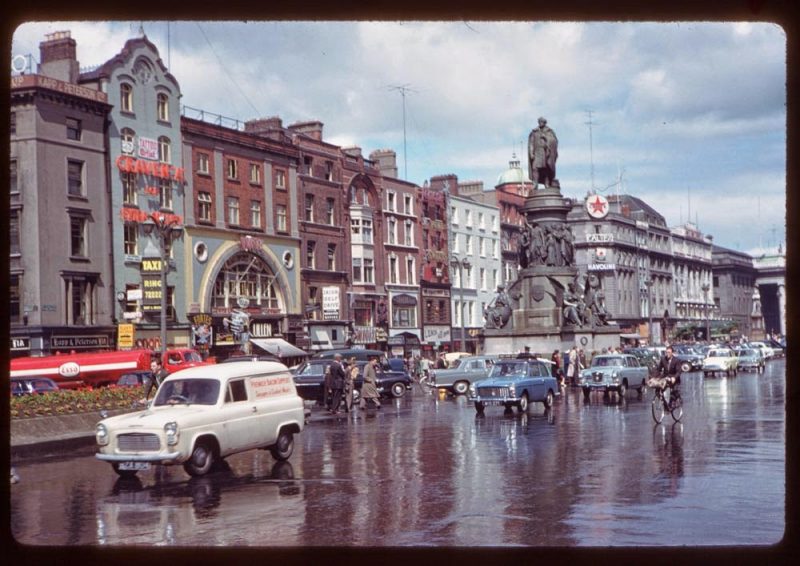

These photographs were taken by American photographer Charles W. Cushman, who travelled the world for 30 years, including a visit to Dublin.

When he died, he left his collection to Indiana State University.

Take a look:

It is now thought that the Viking settlement was preceded by a Christian ecclesiastical settlement known as Duiblinn, from which Dyflin took its name. Beginning in the 9th and 10th century, there were two settlements where the modern city stands. The Viking settlement of about 841 was known as Dyflin, from the Irish Duiblinn (or “Black Pool”, referring to a dark tidal pool where the River Poddleentered the Liffey on the site of the Castle Gardens at the rear of Dublin Castle), and a Gaelic settlement, Áth Cliath (“ford of hurdles”) was further upriver, at the present day Father Mathew Bridge at the bottom of Church Street.The Celtic settlement’s name is still used as the Irish name of the modern city, though the first written evidence of it is found in the Annals of Ulster of 1368.[2] The modern English name came from the Viking settlement of Dyflin, which derived its name from the Irish Duiblinn. The Vikings, or Ostmen as they called themselves, ruled Dublin for almost three centuries, although they were expelled in 902 only to return in 917 and notwithstanding their defeat by the Irish High King Brian Boru at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. From that date, the Norse were a minor political force in Ireland, firmly opting for a commercial life. Viking rule of Dublin would end completely in 1171 when the city was captured by King Dermot MacMurrough of Leinster, with the aid of Anglo-Norman mercenaries. An attempt was made by the last Norse King of Dublin, Ascall mac Ragnaill, to recapture the city with an army he raised among his relations in the Scottish Highlands, where he was forced to flee after the city was taken, but the attempted reconquest failed and Ascall was killed.

By the beginning of the 18th century the English had established control and imposed the harsh Penal Laws on the Catholic majority of Ireland’s population. In Dublin however the Protestant Ascendancy was thriving, and the city expanded rapidly from the 17th century onward. By 1700, the population had surpassed 60,000, making it the second largest city, after London, in the British Empire. Under the Restoration, Ormonde, the then Lord Deputy of Ireland made the first step toward modernising Dublin by ordering that the houses along the river Liffey had to face the river and have high quality frontages. This was in contrast to the earlier period, when Dublin faced away from the river, often using it as a rubbish dump.

During the 18th century, that many of the city’s notable Georgian buildings and street scape schemes were built. Dublin started the 18th century as, in terms of street layout, a medieval city akin toParis. In the course of the eighteenth century (as Paris would in the nineteenth century) it underwent a major rebuilding, with the Wide Streets Commission demolishing many of the narrow medieval streets and replacing them with large Georgian streets. Among the famous streets to appear following this redesign were Sackville Street (now called O’Connell Street), Dame Street, Westmoreland Street and D’Olier Street, all built following the demolition of narrow medieval streets and their amalgamation. Five major Georgian squares were also laid out; Rutland Square (now called Parnell Square) and Mountjoy Square on the northside, and Merrion Square, Fitzwilliam Square and Saint Stephen’s Green, all on the south of the River Liffey. Though initially the most prosperous residences of peers were located on the northside, in places like Henrietta Street and Rutland Square, the decision of the Earl of Kildare (Ireland’s premier peer, later made Duke of Leinster), to build his new townhouse, Kildare House (later renamed Leinster House after he was made Duke of Leinster) on the southside, led to a rush from peers to build new houses on the southside, in or around the three major southern squares.