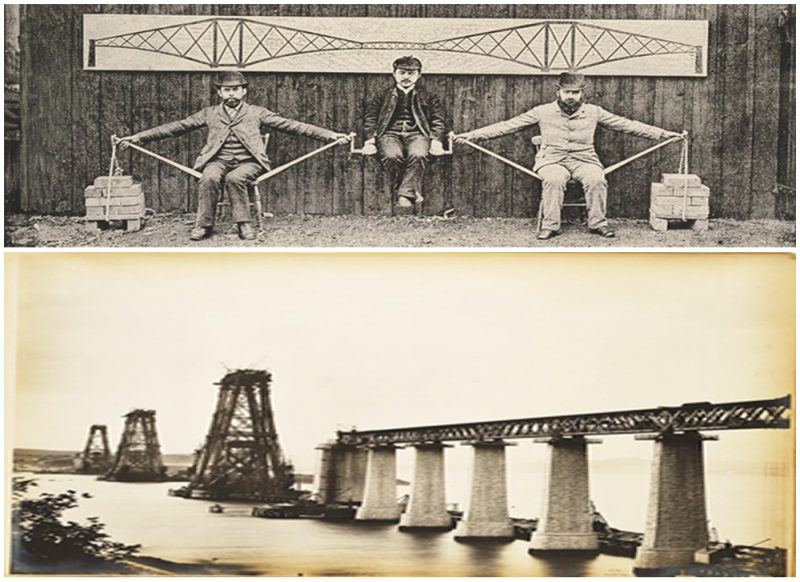

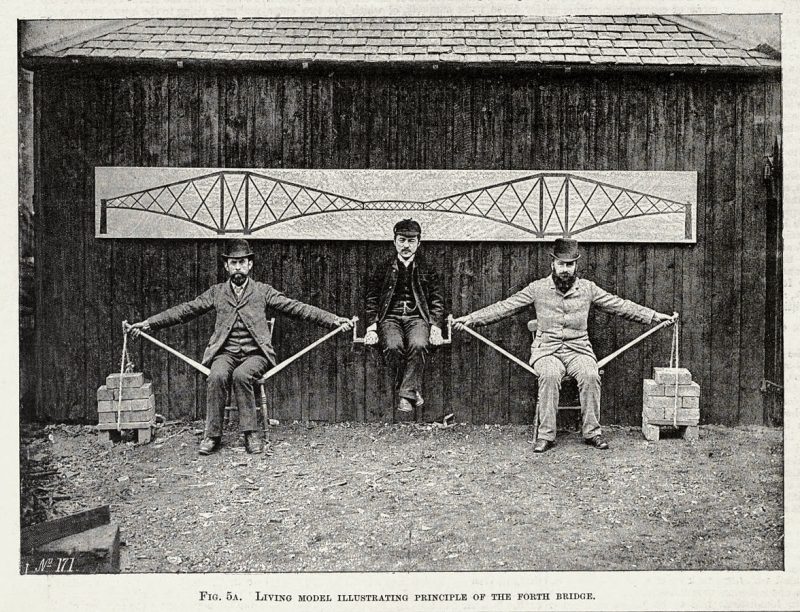

Designed by the English engineers Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker, The Forth Bridge is a cantilever railway bridge over the Firth of Forth in the east of Scotland, 9 miles (14 kilometres) west of Edinburgh City Centre and It is considered an iconic structure and a symbol of Scotland.

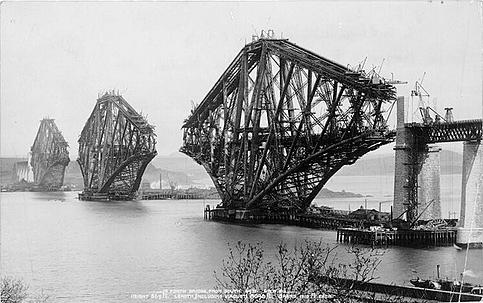

Construction of the bridge began in 1882 and it was opened on 4 March 1890 by the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII. The bridge spans the Forth between the villages of South Queensferry and North Queensferry and has a total length of 8,094 feet (2,467 m). It was the longest single cantilever bridge span in the world until 1917 when the Quebec Bridge in Canada was completed. It continues to be the world’s second-longest single cantilever span. The bridge and its associated railway infrastructure is owned by Network Rail Infrastructure Limited. It is sometimes referred to as the Forth Rail Bridge to distinguish it from the Forth Road Bridge, though this has never been its official name.

The Bill for the construction of the bridge was passed on 19 May 1882 after an eight-day enquiry, the only objections being from rival railway companies. On 21 December of that year, the contract was let to Sir Thomas Tancred, Mr. T. H. Falkiner and Mr. Joseph Philips, civil engineers and contractor, and Sir William Arrol & Co. Arrol was a self-made man, who had been apprenticed to a blacksmith at the age of thirteen before going on to have a highly successful business. Tancred was a professional engineer who had worked with Arrol before, but he would leave the partnership during the course of construction.

The steel was produced by Frederick and William Siemens (England) and Pierre and Emile Martin (France), following advances in the furnace designs by the Siemens brothers and improvements on this design by the Martin brothers, the process of manufacture was thus that it enabled high-quality steel to be produced very quickly.

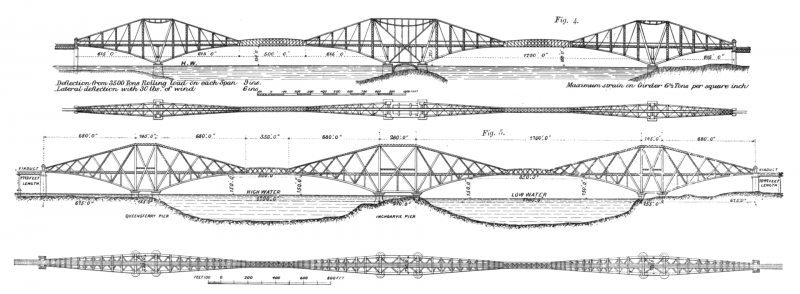

The bridge is 8,094 feet (2,467.05 m) in length, and the double track is elevated 150 feet (45.72 m) above the water level at high tide. It consists of two main spans of 1,700 feet (518.16 m), two side spans of 680 ft (207.3 m), and 15 approach spans of 168 ft (51.2 m). Each main span consists of two 680 ft (207.3 m) cantilever arms supporting a central 350 feet (106.7 m) span truss. The weight of the bridge superstructure was 50,513 long tons (51,324 t), including the 6.5 million rivets used. The bridge also used 640,000 cubic feet (18,122 m3) of granite.

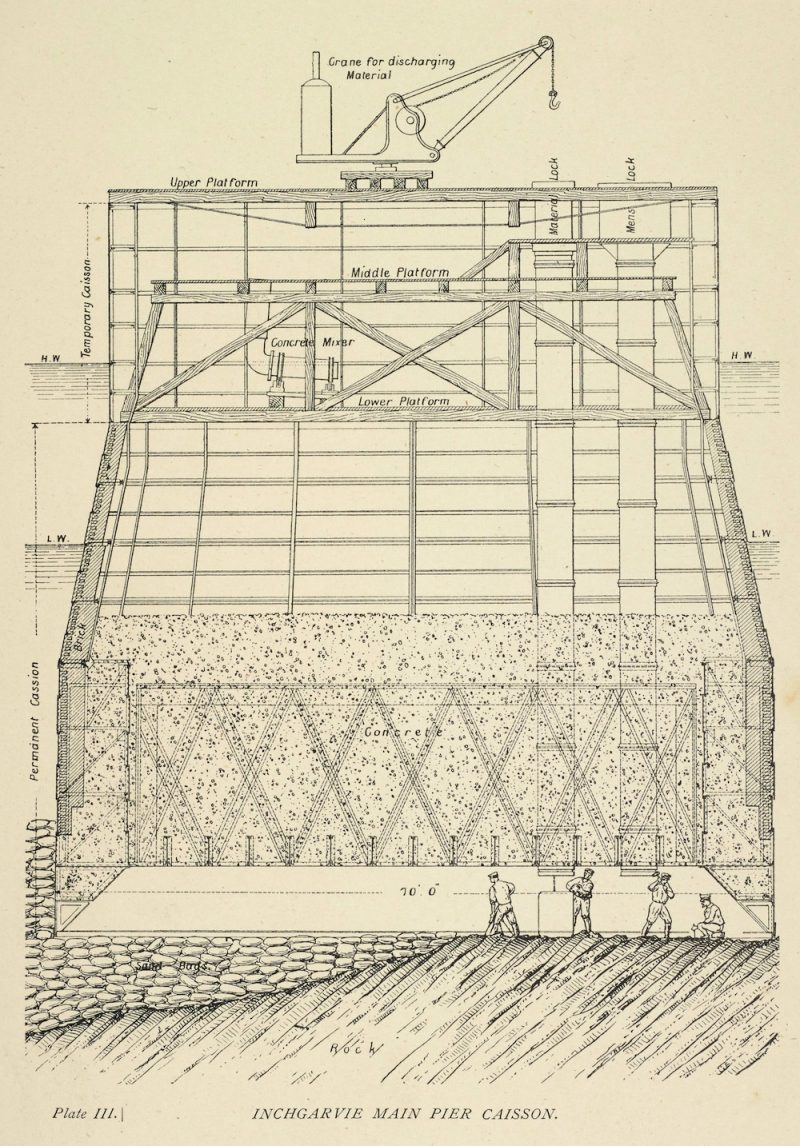

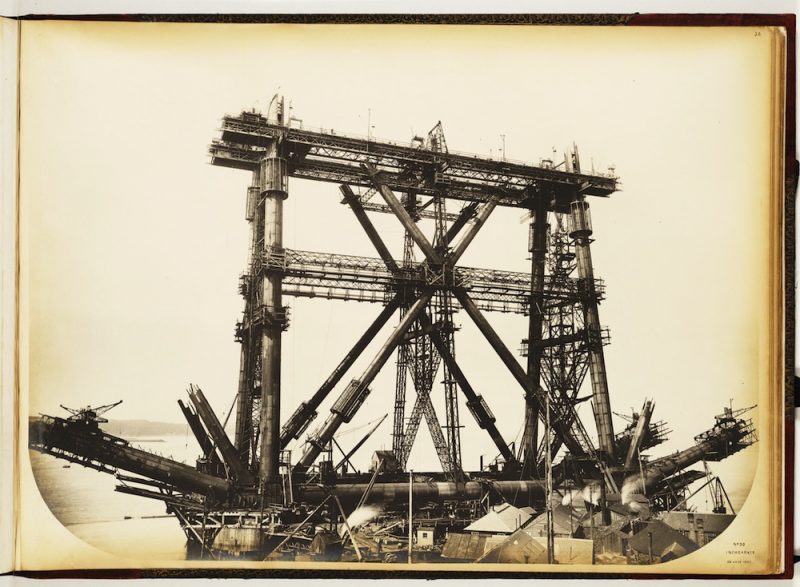

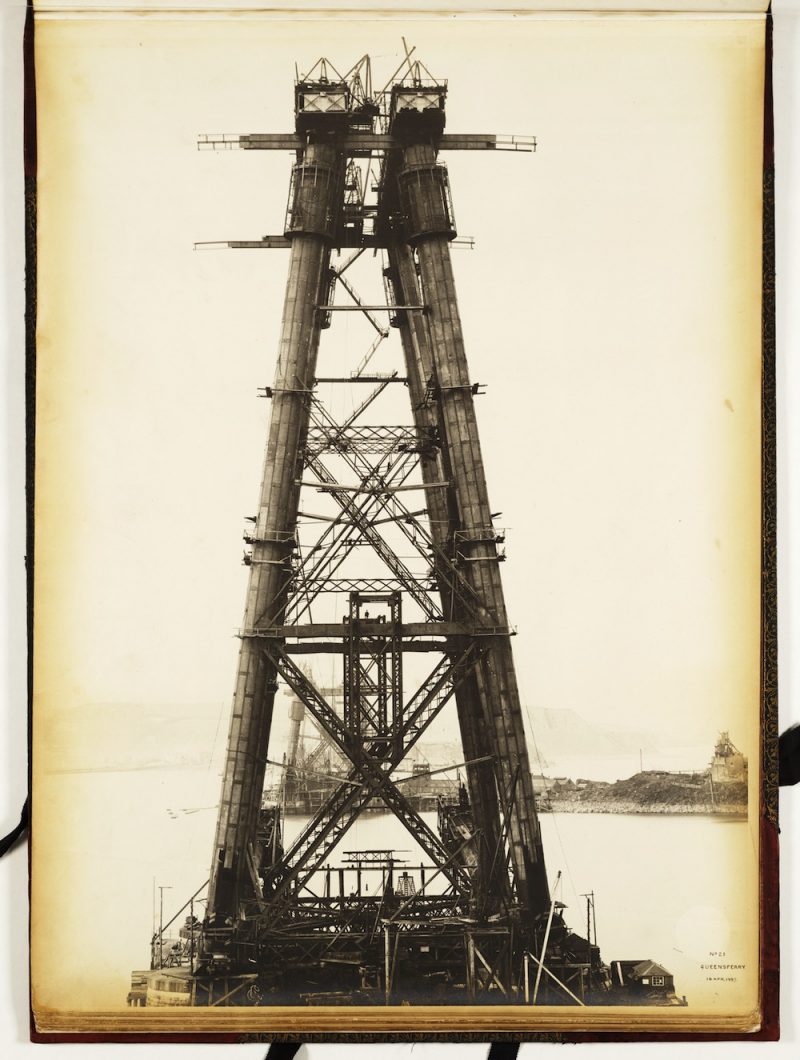

The three great four-tower cantilever structures are 361 feet (110.03 m) tall, each tower resting on a separate granite pier. These were constructed using 70 ft (21 m) diameter caissons; those for the north cantilever and two on the small uninhabited island of Inchgarvie acted as cofferdams, while the remaining two on Inchgarvie and those for the south cantilever, where the river bed was 91 ft (28 m) below high-water level, used compressed air to keep water out of the working chamber at the base.

The bridge uses 55,000 tonnes (54,000 long tons; 61,000 short tons) of steel and 140,000 cubic yards (110,000 m3) of masonry. Many materials, including granite from Aberdeen, Arbroath rubble, sand, timber, and sometimes coke and coal, could be taken straight to the centre where they were required. Steel was delivered by train and prepared at the yard at South Queensferry before being painted with boiled linseed oil before being taken to where it was needed by barge.

The cement used was Portland cement manufactured on the Medway. It required to be stored before it was able to be used, and up to 1,200 tonnes (1,200 long tons; 1,300 short tons) of cement could be kept in a barge, formerly called the Hougomont that was moored off Queensferry.

For a time, a paddle steamer was hired for the movement of workers, but after a time it was replaced with one capable of carrying 450 men, and the barges were also used for people carrying. Special trains were run from Edinburgh and Dunfermline, and a steamer ran to Leith in the summer.

At its peak, approximately 4,600 workers were employed in its construction. Wilhelm Westhofen recorded in 1890 that 57 lives were lost, but in 2005, the Forth Bridge Memorial Committee was set up to erect a monument to the briggers and a team of local historians set out to name all those who died. As of 2009, 73 deaths have been connected with the construction of the bridge and its immediate aftermath.