Just recently the 100-year anniversary of the death of a man known as the missing link from Africa was noted. On March 20th, 1916, Ota Benga had taken a gun and shot himself in the heart and ended his short life. Benga had been an attraction at New York’s Bronx Zoo. In 1904, nearly 40 years after the end of the legal slavery in America, a eugenics movement was highlighted at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri. Many people still recognize Benga as a significant person in history for his part in the story; in documentaries and on social media he is remembered for his sacrifice and for having been one of the causes of the end of racism.

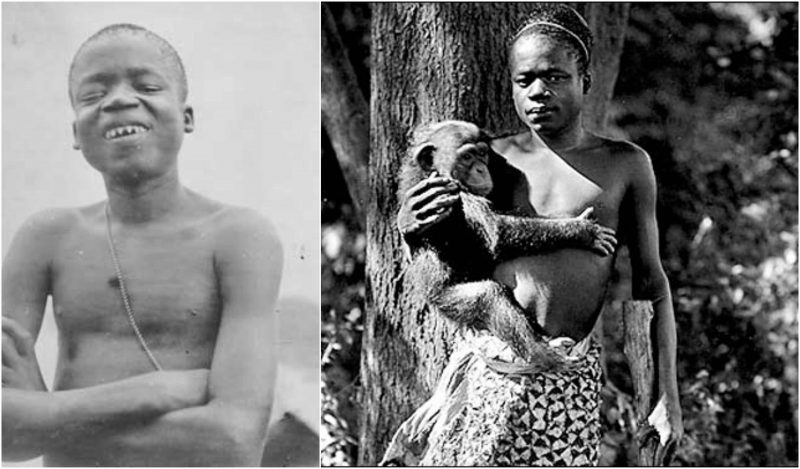

Benga was a 32-year-old Mbuti man from along the Kasai River in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. He was just over 4’11” and had his teeth filed to a point – reportedly a tradition in his tribe. In his earlier life, he had seen some violent things, including the murder of his wife and two children by the Force Publique.

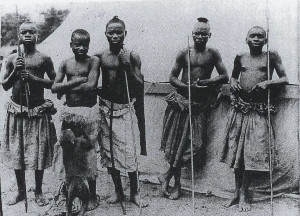

Samuel Phillips Verner was an American businessman traveling in Africa, having been given the task to acquire pygmies for what was known as a “cultural evolution” display at the World’s Fair’s Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Verner encountered Benga in 1904.

Today, it is still unclear as to how Verner actually managed to acquire Benga. For years, it is believed that the Presbyterian missionary claimed to have saved Benga from his cannibalistic tribe when in reality he most likely kidnapped the African man.

From there, Verner used Benga as a recruitment tool and downplayed his understandably distrusting attitude about white men. Verner managed to find more natives and also brought them to the United States to be a part of the exposition’s human displays. The extremely controversial exhibit had shown real humans from a number of different ethnicities; these “exotic exhibits” had been dressed in their native gear on a stage with a reproduction of their homes.

Benga ended up going back to Africa after the fair. He got married for the second time, but his wife died of a snakebite, after which he returned to the United States. At that time, Verner found a place for Benga to stay inside the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He was allowed to roam free until he threw a chair at Florence Guggenheim, which got him transferred back to the Bronx Zoo.

In 1906, nearly 40 years after slavery was abolished, Benga was given the name “the missing link.” He was then put on display at the Bronx Zoo beside a monkey cage. Crowds flocked the zoo in order to see the man. While it entertained some of the people in the crowd, it disgusted others.

The secretary of the zoo was a eugenicist named Madison Grant. He wrote things such as the “dangers” of the “inferior” races outbreeding and mixing breeds with the Caucasians. This particular letter had drawn the attention of many, one of whom was Adolf Hitler. Hitler sent Grant a thank you letter for writing those words.

The zoo had claimed that they were paying Benga for his “work.” However, he was never paid for any of it, even after he assisted some of the other employees with their daily duties.

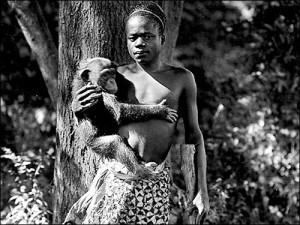

As the crowds visited, they noticed that he had an affection for the monkeys in the cage next to his. Benga was encouraged by the zookeepers to live with the monkeys, slowly having introduced the animals to the men.

The hammock he was given as a bed was in an empty cage and a target had been set up for his bow and arrow. This idea was so that he would feel like he had everything he needed and wouldn’t have to leave. Soon, he was the most popular exhibit in the zoo.

The New York Times had written that he was most likely enjoying himself just like he could have anywhere in Africa. They even went as far as to say that people were beginning to overreact to his being enclosed at the zoo. The newspaper had claimed that people were too sensitive and that it didn’t think it was humiliating or degrading that he was locked up with animals.

Concerning Benga’s display, someone had written that they lived in the south for several years and had not been too fond of the “negro.” However, they still believed that those people are humans and believed it was a shame that the authorities hadn’t stopped the zoo for what they were doing.

Several days after that story had been published in a different newspaper, the exhibit had finally come to an end. Members of the Colored Baptists Ministers Conference had protested that what the zoo was doing was degrading.

Benga was removed from the enclosure, but the damage was done. He was now famous for all of the wrong reasons. Benga was allowed to freely roam again but was constantly followed by crowds who jeered at him.

Trying to get out of New York, he moved down to Lynchburg, Virginia. He had his teeth capped and his name changed to Otto Bingo. He attended school for a short time until his English was good enough to take up work at a tobacco factory.

Soon after that, he longed to return to his home, but that couldn’t happen because World War I had broken out, preventing any passenger ships from traveling. On March 20, 1916, he removed the caps from his teeth, built a ceremonial fire, and stole a gun which he used to shoot himself in his “broken heart.” He was buried in an unmarked grave in Lynchburg. However, what happened to him is a constant reminder of the brutality that poor man suffered just because people enjoyed watching him at the zoo.