Nowadays the world is full of junk food, resulting in a higher rate of obesity for children in developed countries. Whether it’s sweet or salty, children want it. If they were living in the medieval days, their lives would be a shock. If one takes a look at medieval art, it depicts glamorous banquets with endless foods such as meat, cheese, and bread. However, new research suggests children had a much more boring diet than the adults.

Scholars have been studying the milk teeth of young people that lived between the 11th and 16th centuries. They found that they lived on a diet of pap, which consists of flour, milk, and egg yolk as well as bread with broth. The researchers also found that many children had been weaned by the age of one and were fed mainly pap and panada, which is bread with butter served in broth.

Between the ages of two and four, children began to eat tougher foods. By age six they were being introduced to smaller amounts of adult foods like meat and pottage. And by age seven, the children had moved on to typical adult foods.

Surprisingly, researchers looking at the microscopic wear on the teeth found no difference between adults from poorer families and children from all classes. This study suggests that the adults from the wealthy backgrounds enjoyed foods based on their financial status. However, children weren’t as lucky and ate the same boring foods no matter which social background they came from.

An anthropologist at the University of Kent, Dr. Patrick Mahoney, said that the diet of this age did not vary too much between the classes of people. During the medieval period, diet was determined by status. He added that studying the adults’ teeth was the most exciting.

It was previously thought that foods differed for certain adults according to social status; this study showed the researchers that this was not the case for Canterbury children. Their results show that the mixed-feeding in Canterbury would begin by the end of a child’s first year. Mahoney said that the early childhood weaning would have been focused on grain products like bread, butter, porridge, and gruel. Those foods especially were for children with a lower social status. Meat was usually not for the lower status children.

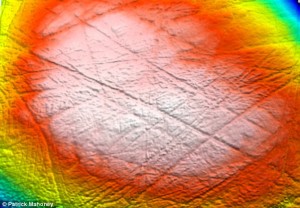

Mahoney and his research team used 3D microscopic imaging in order to analyze the surface of the molar teeth from children. They then combined the experiments with modern teeth enamel and compared the two in order to build a picture of what the people at the time were eating. What’s nice about the study is that it does not require that the teeth be damaged in order to conduct it because, unlike the analysis that looks at isotopes from food, it can be used to study the rare and fragile teeth of the remains.

The latest study provides a key insight into the lives of those children that lived in that period. These children were often depicted by Chaucer and his contemporaries. Many of those historical texts exist from the time and provide details about the diets of the rich and poor. However, the research done in Canterbury shows that the children did not really benefit from better food if they came from a wealthier family.

The researchers were able to determine the status of the buried children from some of the historical texts that indicated that those who were buried in the Priory were from wealthier families. Those remains found in the adjacent cemetery were from poorer families who could afford the burial fees from the St. John’s Hospital nearby.

Mahoney had explained that those children were from the pre-industrial revolution; before processed sugars would have formed a key component in their diet. However, this meant the children had far less dental decay than today’s children.