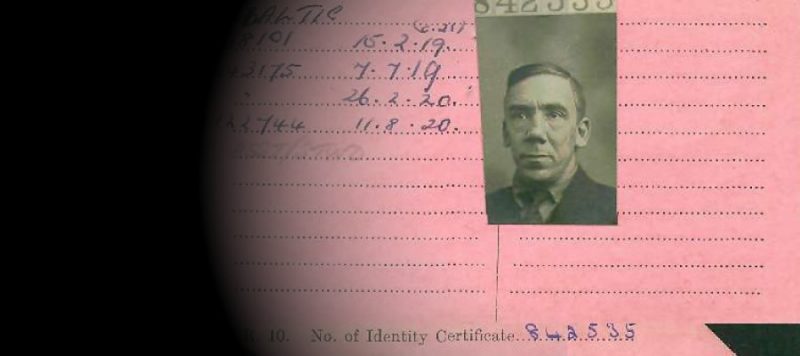

One of the most famous Titanic survivor stories is that of Charles Joughin. The man who somehow drank his way through the Titanic disaster and lived to tell the tale. Here is an account of this Titanic survivor and his bizarre story that some still find hard to swallow. When Joughin signed on he gave his age as 30 and his address as Elmhurst, Leighton Road, Southampton. The 1911 census confirms that his wife Louise, aged 31, from Douglas, Isle of Man, his daughter Agnes, aged three, born in Kirkdale, Liverpool, and his son Roland, aged one, born in Southampton, were also living at this address.

When Joughin signed on he gave his age as 30 and his address as Elmhurst, Leighton Road, Southampton. The 1911 census confirms that his wife Louise, aged 31, from Douglas, Isle of Man, his daughter Agnes, aged three, born in Kirkdale, Liverpool, and his son Roland, aged one, born in Southampton, were also living at this address.

Like any cruise ship of current times, the Titanic was designed as one big party boat. You can’t go on a cruise ship without entertaining the idea of having a few cocktails to go along with the view, and the Titanic was no different. According to the ship’s manifest, the drink order for the Titanic included 1,500 bottles of wine, 15,000 champagne glasses, 20,000 bottles of beer and stout, and at least 850 bottles of spirits. The cargo manifest reveals further reserves of 17 cases of cognac, 70 cases of wine and 191 cases of liquor. This was all in addition to the personal stocks of booze that passengers were sure to have included as

He was on board the Titanic for her delivery trip from Belfast to Southampton. When he signed-on again, in Southampton on 4 April 1912, he gave his address as Elmhurst Leighton Rd., Southampton. He transferred from the Olympic. As Chief Baker he received monthly wages of £12.

When the ship hit an iceberg on the evening of 14 April, at 23:40, Joughin was off-duty and in his bunk. According to his testimony, he felt the shock of the collision and immediately got up. Word was being passed down from the upper decks that officers were getting the lifeboats ready for launching, and Joughin sent his thirteen men up to the boat deck with provisions to the lifeboats: four loaves of bread apiece, about forty pounds of bread each. Joughin stayed behind for a time, but then followed them, reaching the Boat Deck at around 00:30.

He joined Chief Officer Henry Wilde by Lifeboat 10. Joughin helped, with stewards and other seamen, the ladies and children through to the lifeboat, although, after a while, the women on deck ran away from the boat saying they were safer aboard the Titanic. The Chief Baker then went on to A Deck and forcibly brought up women and children, throwing them into the lifeboat.

Joughin fortified himself with alcohol, threw deck chairs overboard for flotation devices, rode the stern down and claims to have stepped into the water without getting his hair wet. He claims to have hung on to the side of Collapsible B for hours with most of his body submerged in the icy water, yet survived with virtually no ill effects.

He gave this statement at the British enquiry:

“I got to the starboard side of the poop; found myself in the water. I do not believe my head went under at all. I thought I saw some wreckage, swam towards it and found collapsible boat (B) with Lightoller and about twenty-five men on it. There was no room for me. I tried to get on, but was pushed off, but I hung around. I got around to the opposite side and cook Maynard, who recognised me, helped me and held on to me.”

Although he was assigned as captain of Lifeboat 10, he did not board; it was already being manned by two sailors and a steward. He went below after Lifeboat 10 had gone, and “had a drop of liqueur” (a tumbler half-full of liqueur, as he went on to specify) in his quarters. He then came upstairs again after meeting “the old doctor” (possibly Dr. William O’Loughlin), quite possibly the last time anyone ever saw him. When he arrived at the Boat Deck, all the boats had been lowered, so he went down into the B Deck promenade and threw about fifty deck chairs overboard so that they could be used as flotation devices.

Joughin then went into the deck pantry on A Deck to get a drink of water and, whilst there, he heard a loud crash, “as if part of the ship had buckled”. He left the pantry, and joined the crowd running aft toward the poop deck. As he was crossing the well deck, the ship suddenly gave a list over to port and, according to him, threw everyone in the well in a bunch except for him. Joughin climbed to the starboard side of the poop deck, getting hold of the safety rail so that he was on the outside the ship as it went down by the head. As the ship finally sank, Joughin rode it down as if it were an elevator, not getting his head under the water (in his words, his head “may have been wetted, but no more”). He was, thus, the last survivor to leave the RMS Titanic.

According to his own testimony, he kept paddling and treading water for about two hours. He also admitted to hardly feeling the cold, most likely thanks to the alcohol he had imbibed. (Large quantities of alcohol generally increase the risk of hypothermia – but there is also evidence to suggest that a certain level of alcohol can slow down heat loss and prolong survival in cold conditions.) When daylight broke, he spotted the upturned Collapsible B, with Second Officer Charles Lightoller and around twenty-five men standing on the side of the boat. Joughin slowly swam towards it, but there was no room for him. A man, however, cook Isaac Maynard, recognised him and held his hand as the Chief Baker held onto the side of the boat, with his feet and legs still in the water. Another lifeboat then appeared and Joughin swam to it and was taken in, where he stayed until he boarded the RMS Carpathia that had come to their rescue. He was rescued from the sea with only swollen feet.

Joughin survived the Titanic and his heroism under the influence has gone all but unnoticed over the years. Joughin died at age 78 in 1956 in Patterson, New Jersey. In a letter to the author of “A Night to Remember,” Walter Lord, Joughlin wrote:

Mr Walter Lord

Dear Sir,

Some secretaries brought to my notice your very splendid article “A Night to Remember” in the current issue of “The Ladies Home Journal.”

Most written accounts were hair-raising scenes which did not actually occur, except in the last few moments when those left behind made a mad rush towards what they considered a safer place, the Poop Deck. Fortunately I was all alone, when the big list to port occurred. I was able to straddle the Starboard rail (on A deck) and stepped off as the ship went under. I had expected suction of some kind, but felt none. At no time was my head underwater. just kept moving my arms and legs and kept in an upright position. No trick at all with a left-belt on. Your account of the upturned collapsible with Col.Gracie aboard was very correct. Most of the crew were familiar with life boat and Fire stations as they had manned the “Olympic” (a sister ship) previously. Some curious things are done at a time like this. Why did I lock the heavy iron door of the Bakery, stuff the heavy keys in my pocket, alongside two cakes of hard tobacco.

My conclusions of cause: Grave error on part of Captain Smith kept course in spite of ice warnings and severe drop in temperature from 5 P.M.

Loss of life: life boat shortage, for the number of passengers and crew, but many more could have been saved, had the women obeyed orders. In those circumstances the crew are helpless.

After surviving the Titanic disaster, he returned to England, and was one of the crew members who reported to testify at the British Wreck Commissioner’s inquiry headed by Lord Mersey. In 1920, Joughin moved permanently to the United States to Paterson, New Jersey. According to his obituary he was also on board the SS Oregon when it sank in Boston Harbor. He also served on ships operated by the American Export Lines, as well as on World War II troop transports before retiring in 1944.

He divorced shortly thereafter; however, a daughter Agnes was born from his first marriage. After moving back to New Jersey, he remarried Mrs. Annie E. Ripley, and together raised Annie’s daughter Rose. Annie’s death in 1943 was a great loss from which he never recovered. Twelve years later, Joughin was invited to describe his experiences in a chapter of Walter Lord’s book, A Night to Remember.

Soon afterwards, his health rapidly declined, dying in a Paterson hospital on 9 December 1956 after two weeks with pneumonia at the age of 78 being buried alongside his wife in the Cedar Lawn Cemetery, in Paterson, New Jersey.

Sources titanicuniverse / wikiencyclopedia-titanica