The Holocaust is one of the worst historic events to ever happen. Although many people died, there were some that got lucky and survived or escaped the hell awaiting them.

One particular Jew known as Wladyslaw Szpilman was a talented pianist. He was on the verge of going crazy, he was starving, and knew that he was the next one to be gassed in a Nazi death factory, just like the rest of his family. Trying to pass the time before being killed, he crawled into a house in the moonscape that was Warsaw in 1944.

However, he was not ready to die and he held onto dear life, living through awful horrors during the German occupation. He had huddled in the freezing cold shell of 223 Neipodleglosci Avenue and surprisingly, salvation finally came. Little did this man know, salvation would come from one of the most unlikely people – an officer of the regime that had killed his entire family, along with six million other Jews.

Wilm Hosenfeld was the bearer of the Iron Cross First Class for gallantry in World War I. He was a Nazi officer who had forgotten who he worked for. He forgot all about the Fuehrer he once idolized and promised to serve those he had once persecuted and rounded up until he died.

While saving Jews and getting them to safety, he saved Szpilman. He brought the man food and kept his survival secret from the S.S. death squads that constantly roamed the ruined Polish capital.

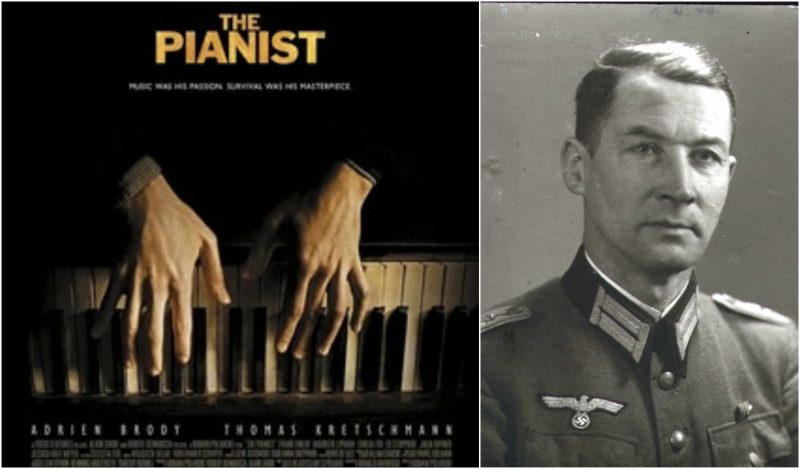

This man who found his humanity had inspired the 2003 Roman Polanski, Robert Benmussa, and Alain Sarde film called The Pianist. The movie won three academy awards. It won Oscars for best director, best actor, and best-adapted screenplay.

In the movie, Hosenfeld’s character had a rather small part. Now, a written biography finally unveils just how much he did, unveiling his humanity during the Nazi rule of Poland. The officer considered himself religious and was often sickened by just how much destruction and death was being caused.

The biography, titled I Always See the Human Being Before Me, was written by Hermann Vinke. It finally gives readers the real details of the man who once worshiped Hitler as a true genius. However, in 1940, he finally rediscovered his own conscience before the war was over, helping those who needed it most.

The book first looks into the life of Hosenfeld, but then shows letters, diaries, memories from his children, and even some pieces from the widow Szpilman. Szpilman still lives in Warsaw, showing readers that the act of mercy Hosenfeld showed was not a short-lived, one-time ordeal.

Vinke said that the moral compass of Hosenfeld had remained intact throughout the remainder of the war. He did not only save Szpilman, but also numerous Polish citizens, among them other Jews. They were all saved from certain death.

Vinke believes there were at least 60 Jews who owed their lives to this Nazi who saved them. He was considered both a savior to these people and yet a victim. He was eventually caught towards the end of the war and sentenced to life in a Soviet prison. He never saw his family again. In the blink of an eye, he risked his own life to save others. The officer was honored just a few years ago as one of the “Righteous Among the Nations.” This was a recognition for a non-Jew who saved Jews. Israel is the one country that saw this as a man needing the award.

Hosenfeld had first pledged his loyalty to Kaiser Wilhelm II in Imperial Germany, then he pledged it to Adolf Hitler. This oath of loyalty was so strict that it was nearly impossible to break, as well as unthinkable. He had joined the Nazi Party in 1935. He was one of the millions, of Germans who had helped Hitler wipe clean the shame of 1918 and the collapse of Imperial Germany. Hosenfeld and his brother, Rudolf, marched with 500,000 men at the Nuremberg Rally of 1936.

He had written in his diary that the new weapons, tanks, and planes had excited him. He had even sung the Horst Wessel Lied, the Nazi Party hymn. At first, he had seen joining this party as nothing but excitement, but as he saw more death and destruction, he began to see what the Nazi Party was really for. He saw Hitler for who he really was. He wrote in his diary in 1938 that he began feeling guilty for killing these Jews, but he was still working for Hitler.

In 1939, shortly before the Germans invaded Poland, he was in uniform in Fulda. His wife was upset that he was going off to war yet again, at 44 years old. She was not wrong – he and many others began to cross the border and eventually turned Poland into a major slaughterhouse, spending the entire time of the war there.

His first destination was Pabianice, where he was first involved in building and running a POW camp. He was then stationed in Wegrow in December 1939, where he had remained in a battalion until he was moved to Jadow at the end of May 1940. Then, in July 1940, he was transferred to Warsaw for the rest of the war.

Hitler absolutely hated Poland. He either captured or killed the people, or he had them enslaved. No other country had suffered as much as Poland did during the war. Three million were murdered and entire cities were completely wiped clean. Hosenfeld witnessed those murders daily.

When Hosenfeld housed the first Polish prisoners, he had written to his wife about their starving, terrible conditions. He believed that the Polish people had deserved his sympathy, writing to her that he wanted to help them.

It was during, the change in Hosenfeld that had led to the salvation of Szpilman. Hosenfeld first began by giving the POWs apples and nuts. He then released some of them without letting his superiors know. One Polish woman had even given him money because he let her husband and sons go free.

He had written to his wife again on November 10, 1939, nearly two months after the invasion, expressing his fear that after each house was invaded, all he could hear were shrieks of terror as people were caught and murdered. He had also written that he was wearing the uniform of a terrible person.

When he was in Lodz, he wrote to his wife explaining that children had been loaded into cattle wagons as if they were cattle themselves.

During his time in Warsaw, Hosenfeld had used his position to save many people regardless of their background. He even helped one anti-Nazi ethnic German who was in danger of being arrested by the Gestapo. For some of those people, he had to produce false papers and jobs at the sports stadium he was working at.

One particular woman he met was running down the road while he was riding a bike. He stopped her to ask what’s wrong. She said that she was pregnant and her husband was locked up in a nearby concentration camp. She was crazy enough to run to the camp to ask for his release, but Hosenfeld took down her husband’s name instead and promised her that he would be released in three days.

Another event that happened was when Hosenfeld learned the Gestapo rounded up men which included a brother-in-law of a priest who was in a Polish underground. The men were in a truck taking them to a concentration camp. Hosenfeld found out that the brother-in-law was about to be executed when he waved down the truck. He told the drivers he needed one man and pretended to pick out the brother-in-law randomly. Thanks to him, the man survived the entire war.

One scene of the biggest war crime known today is the Warsaw Ghetto. The area stunk and was crammed with people who were being taken north to the extermination camp of Treblinka. Hosenfeld wrote to his wife explaining that he wished he could kill the S.S. men who were in charge of that ghetto. He thought they were cowards, punishing the innocent.

One Jew, named Leon Warm, had escaped from a train to Treblinka during the 1942 deportations from Warsaw. He made it back into the city and survived with the help of Hosenfeld, who employed Warm in the sports stadium under a false identity. After the war, Warm was actually one of many who had pleaded with Russia to release Hosenfeld for saving him.

Again, he wrote to his wife to explain that all of the Nazis believed they had won the war when really they were the real losers. They deserved to lose after mass murdering the Jews; Germany would never be forgiven for what they had done.

In one of his final acts, Hosenfeld saved Szpilman. Szpilman was actually another man who pleaded with Russia to release the man who saved him. In 1946, Hosenfeld wrote to his wife with all of the names of the people he saved. He had begged her to contact those people who should then beg Russia to release him.

Sadly, Hosenfeld suffered terribly in Russian captivity. He endured torture and was overworked and malnourished. He ended up dying in a Soviet concentration camp on August 13, 1952. He died from a rupture of the thoracic aorta from being tortured.

Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3334954/The-good-Nazi-Courageous-story-guilt-wracked-German-officer-saved-Pianist-inspired-Hollywood-blockbuster.html