The trail was mostly littered with unused supplies and discarded belongings.

People have always been forced to make journeys towards the pastures green, in search of better life prospects. Some of these migrations leave a mark on the history pages due to their impact on the generations that followed those who made these trips. Perhaps the most significant migration in modern American history is known as Oregon Trail when hundreds of thousands walked for thousands of miles in search of opportunity in the frontier land.

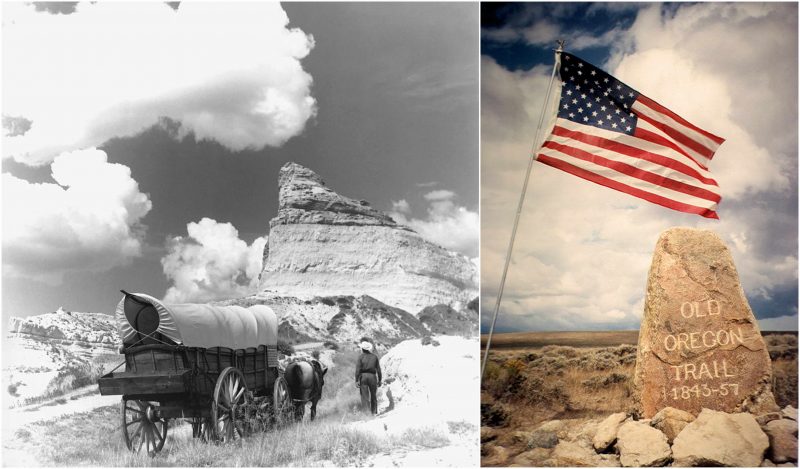

Stretching over 2,000 miles across the continental divide and Great Plains, the Oregon Trail ended in the gold fields of California. Between the years of 1840 and 1860, some 400,000 pioneers undertook the epic journey through desserts and ruthless rivers facing disease outbreaks and freak accidents. Following are some of the unknown facts about the famous course that once served as the doorway to the American Wild West.

The Trail was not a Single Path

Cutting through Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming and ending in Oregon the landmark path was adopted by most of the emigrants, however as it turns out this was not the sole route for the pioneers looking for new life in California. The main reason for the alternative path was to avoid land chokes by thousands of travellers which raised storms of dust behind them. Some people went off to find green pastures in order to keep their livestock alive and rest a few days before carrying on to the final destination.

This overtime created hundreds of branches sprouting out of the main trail and many people adopted these routes in order to stay alive all through 2,000 miles stretch of mostly barren and treacherous land.

A Protestant Missionaries’ couple Kick-started the Mass migration

Prior to the pioneers’ waves swept through the Oregon Trail to the West, the path was mostly in use by the professional explorers and other tradesmen. However, the road was considered too challenging and dangerous to tread through with families, especially young kids.

The reputation of the road to west changed when a couple of Missionaries, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, decided to make the trip up the road in 1836 soon after they tied the knot. Their destination was to Walla Walla Valley, aiming to spread the Gospels amongst Cayuse Indians. Narcissa loved to write about her journeys in the most articulate way; her letters that she wrote to her family back home presented a completely different picture of the Rocky Mountains. However it was not until 1843 when the first wave of migrants made the journey under Whitman’s’ supervision, which helped some 1,000 people successfully cross the trail all the way into West, the exodus was later immortalized by the title the ‘Great Migration’. Merely a few years later the number of people making the journey skyrocketed to some 50,000 every year.

The Icon of Oregon Trail ‘Conestoga’ Wagon was rarely used on the path

Mostly in the countless documentaries and movies depicting some aspects of the Oregon Trail, the Conestoga wagons are shown as the main mean of transportation by the pioneers, however, it is not entirely correct. Conestoga wagons were not particularly preferred by the travellers for their larger sizes and lack of manoeuvrability on the rugged terrains to the West. The most common wagons used on the Oregon Trails were much older vehicles known simply as the ‘Prairie Schooners’. These were strong bulky ships like carts driven by mules or oxen. Capable of covering more than 15 miles on a typical day, these carts could also carry over a ton of cargo. Due to their rather bumpy and uncomfortable ride, most of the travellers preferred to walk alongside their Schooners filled with tons of belongings and sometimes children or sick people.

Indian Attacks on the Path were extremely rare

Contrary to the popular belief of savage Indian hordes attacking and plundering the caravans, there were hardly any such incidents all through the famous exodus to the West.

In most of the cases, local Indian tribes helped the travellers and did trade with them that assisted the pioneers towards their journeys. The famous circle formations of carts in the night were not aimed at protecting against Indians, it was rather a clever approach to stop the animals carrying the wagons from wandering off.

The trail was mostly littered with unused supplies and discarded belongings

The sheer number of people treading their way towards Oregon presented an opportunity of trade for a good number of legitimate traders, however, many cons tried to cash the moment by offering supplies for the trip. In many cases, the naive travellers were lured into thinking that their supplies would not suffice the journey and were then forced to buy from the con traders. Consequently, a large volume of supplies had to be dumped by the pioneers after realizing the mistake.

It is believed that during the Gold Rush of 1849 the travellers had to discard an enormous volume of bacon; 20,000 tons by some estimates, outside the walls of Fort Laramie in Wyoming, gaining the title of ‘Camp Sacrifice’.