On March 22, 1944, fifteen soldiers of the U.S. Army, including two officers, landed on the Italian coast about 15 kilometres north of La Spezia, 250 miles behind the then established front, as part of Operation Ginny II.

They were all properly dressed in the field uniform of the U.S. Army and carried no civilian clothes. Their objective was to demolish a tunnel at Framura on the important railroad line between La Spezia and Genoa. Two days later, the group was captured by a party of Italian Fascist soldiers and members of the German Heer.

They were taken to La Spezia, where they were confined near the headquarters of the 135th Fortress Brigade, which was under the command of German Colonel Almers. The immediate, superior command was that of the 75th Army Corps, commanded by Dostler.

The captured U.S. soldiers were interrogated and one of the U.S. officers revealed the story of the mission. The information, including that it was a commando raid, was then sent to Dostler at the 75th Army Corps.

The following day (March 25), Dostler informed his superior, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commanding general of all German forces in Italy, about the captured U.S. commandos and asked what to do with them. According to Dostler’s adjutant officer, Kesselring responded by ordering the execution.

Later that day, Dostler sent a telegram to the 135th Fortress Brigade ordering that the captured soldiers be executed. This order was an implementation of Hitler’s secret Commando Order of 1942 which required the immediate execution without trial of commandos and saboteurs.

German officers at the 135th Fortress Brigade contacted Dostler in an attempt to achieve a delay of their execution. Dostler then sent another telegram ordering Almers to carry out the execution.

Two last attempts were made by the officers at the 135th to stop the execution, including some by telephone, because they knew that executing uniformed prisoners of war was a direct violation of the 1929 Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War.

These efforts were unsuccessful and the fifteen Americans were executed on the morning of March 26, 1944, at Punta Bianca south of La Spezia, in the municipality of Ameglia. Their bodies were buried in a mass grave that was then camouflaged. Alexander zu Dohna-Schlobitten, a member of Dostler’s staff who was unaware of the secret Commando Order and who had refused to sign the execution order, was dismissed from the Wehrmacht for insubordination.

Trial, execution, and notoriety

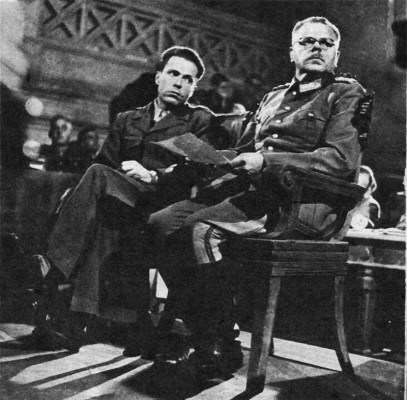

Dostler became a prisoner of the Americans on 8 May 1945 and was put before a military tribunal at the seat of the Supreme Allied Commander, the Royal Palace in Caserta, on 8 October 1945.[4] In the first Allied war trial, he was accused of carrying out an illegal order.

In his defense, he maintained that he had not issued the order, but had only passed along an order to Colonel Almers from supreme command, and that the execution of the OSS men was a lawful reprisal.

Dostler’s plea of Superior Orders failed because ordering the execution, he had acted on his own outside the Führer’s order.

The military commission also rejected his plea, declaring that Dostler’s execution of U.S. soldiers was in violation of Article 2 of the 1929 Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War, which prohibited acts of reprisals against prisoners of war.

The commission stated that “No soldier, and still less a Commanding General, can be heard to say that he considered the summary shooting of prisoners of war legitimate even as a reprisal.”

Under the 1907 Hague Convention on Land Warfare, it was legal to execute spies and saboteurs disguised in civilian clothes or enemy uniforms but excluded those who were captured in proper uniforms.

Since fifteen U.S. soldiers were properly dressed in U.S. uniforms behind enemy lines and not disguised in civilian clothes or enemy uniforms, they were not to be treated as spies but prisoners of war, which Dostler violated.

The trial found General Dostler guilty of war crimes, rejecting the defense of superior orders. He was sentenced to death and executed by a 12 man firing squad at 0800 hours on December 1, 1945 in Aversa.

The execution was photographed on black and white still and movie cameras. Immediately after the execution Dostler’s body was lifted onto a stretcher, shrouded inside a white cotton mattress cover and driven away in an army truck.

His remains were subsequently buried in Grave 93/95 of Section H at Pomezia German War Cemetery. Sources wiki / rarehistoricalphotos

Many people taking part in firing squads intentionally miss their target, as they do not want to be the one responsible for the individuals death. Often times, they would even aim for non-vital areas of the body for the same reasons, knowing that the person was going to die regardless, and didn’t want the kill-shot on their conscious.

Another reason is that a lot of soldiers feel that it is immoral to execute a defenceless or captured prisoner, despite any crimes the person has committed. This is why there are so many people used in a firing squad. To ensure a quick death. The fewer participants, the more likely it is to cause mental trauma to the gunmen. There is something relieving about knowing that others are there to share the burden of having just taken a life. It’s related to diffusion of responsibility.

One method used to alleviate such burden is to have some of the weapons loaded with blank rounds, so that none of the participants are absolutely sure they are responsible for the kill.

Although loading a weapon with a blank round does not alleviate the shooters from a sense of responsibility.

The person who has the blank knows who fired the blank, due to the night-and-day difference in felt recoil. Blanks do not create recoil as there is no mass in front of the propellant charge.

The purpose of loading a blank is so that none of the other soldiers in the squad know which one of them had the blank in their rifle.

This creates a communal sense of knowing that at least one of the shooters had no hand in the execution, but no one knows who except for the man with the blank loaded in his rifle, thereby allowing any of them to psychologically alleviate themselves of any guilt they may have, since as far as their comrades know; they did not fire a lethal shot.