Whether driven by greed, ideology or revenge, here are six infamous Cold War spies who supplied the enemy with highly classified intelligence.

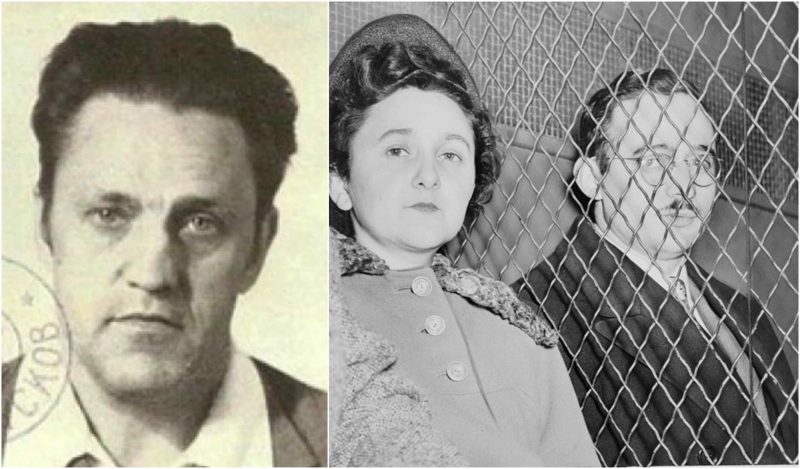

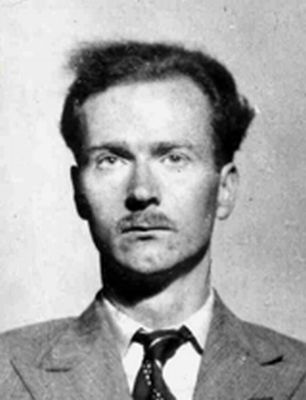

1. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Julius Rosenberg along with his wife, Ethel Rosenberg became infamous figures in American history when they were convicted, of giving military secrets to the Soviet Union in the early 1950s.

When they got married in 1939, the year Julius earned a degree in electrical engineering, the two were already active members of the Communist Party. By 1943, however, the Rosenbergs dropped out of the Communist Party to pursue Julius’s espionage activities. Julius obtained a job as a civilian engineer with the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and he and Ethel began working together to disclose U.S. military secrets to the Soviet Union.

Early in 1945, Julius was fired from his job with the Signal Corps when his past membership in the Communist Party came to light but in a meantime, they recruited Ethel’s brother David Greenglass, an Army machinist working on the Manhattan Project. He was turning over handwritten notes and sketches pertaining to the atomic bomb. Also, other Rosenberg recruits purportedly delivered thousands of pages of documents detailing new radar and aircraft technologies.

After the Soviets detonated their first atomic bomb in 1949, the U.S. government began an extensive hunt to find out who had provided them with the knowledge to make such a weapon. At trial following their 1950 arrest, Greenglass testified against them, and a judge sentenced them to death, declaring their crime “worse than murder.” President Dwight D. Eisenhower then sealed their fate by denying a petition for executive clemency. The two were sent to the electric chair at New York State’s Sing prison on June 19, 1953, marking the first time American civilians had ever been executed for espionage.

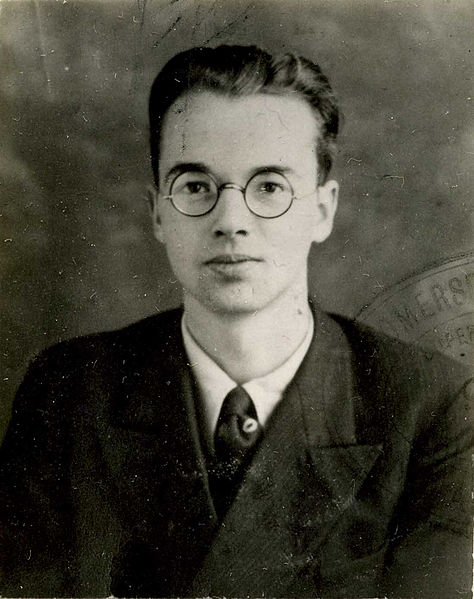

2. Klaus Fuchs

Born in 1911 in Germany, into a Lutheran family, Fuchs joined the Communist Party of Germany and fled to England following the rise of the Nazis in 1933. A brilliant young scientist, he earned his doctorate in Physics from the University of Bristol in 1937 and was invited to study at Edinburgh University.

He obtained British citizenship in 1942 and subsequently signed the Official Secrets Act. In the following year, Fuchs was part of a British delegation of scientists sent to Columbia University in New York to work on the Manhattan Project. His job was to he calculate the approximate energy yield of an atomic explosion. He specialized in researching implosion methods, focusing in particular on the “Fat Man” implosion bomb. Additionally, he was present at the Trinity Test on July 16, 1945.

Fuchs made contact with a Soviet courier almost as soon as he’d arrived in the U.S, a man he knew only as Raymond, but who was in fact, Harry Gold – courier who worked with David Greenglass. Fuchs and Gold met several times.

Following an FBI and British investigation, Fuchs was convicted of espionage in Great Britain for supplying atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. He confessed, telling the authorities that he “had complete confidence in Russian policy” and that “the Western Allies deliberately allowed Russia and Germany to fight each other to the death.”

Fuchs’s espionage likely led the U.S. to cancel a 1950 Anglo-American plan to give Britain American-made atomic bombs. He was convicted in 1950 and sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment, the maximum for espionage because the Soviet Union was classed as an ally at the time. In December 1950 he was stripped of his British citizenship. After nine years in a British prison, he immigrated to East Germany, where he continued working as a nuclear physicist until his retirement in 1979. A winner of the Karl Marx Medal, East Germany’s highest civilian honor, Fuchs died in 1988 at age 76.

3. Ray Mawby

Born in 1922 and educated at Long Lawford school, Raymond Llewellyn Mawby worked as an electrician and entered politics through his involvement with trade unionism. He was an official in the Rugby branch of the Electrical Trades Union and became the first president of the Conservative Trade Unionists’ national advisory committee.

Mawby actively campaigned against legalizing male homosexual acts. In 1983 he was deselected as an MP.

For Conservative Party members like him, hatred of communism was practically a prerequisite. Yet in 2012, a dozen years after his death, a BBC reporter unearthed a file showing that Mawby had been a mole for Czechoslovakia, then part of the Soviet bloc.

According to the files, Czech spies approached Mawby in November 1960 at a cocktail party and persuaded him to begin supplying political gossip on a regular basis for cash payments. He was known to be a gambler and the spies hoped they could exploit that particular weakness.

At the beginning the Czechs played Mawby cautiously, asking him for relatively unhelpful gossip on trade unions before requesting that he start supplying more sensitive information. Each time he handed over details he was paid £100 – a handsome regular income on the side at a time when the annual MP’s salary was around £3,200. In later years, they upped the total to £400 per year. Mawby’s relationship with the Czech spy service appeared to continue up until November 1971 when his file as closed.

Remarkably, some Labour Party politicians are also known to have been in cahoots with the Czechs.

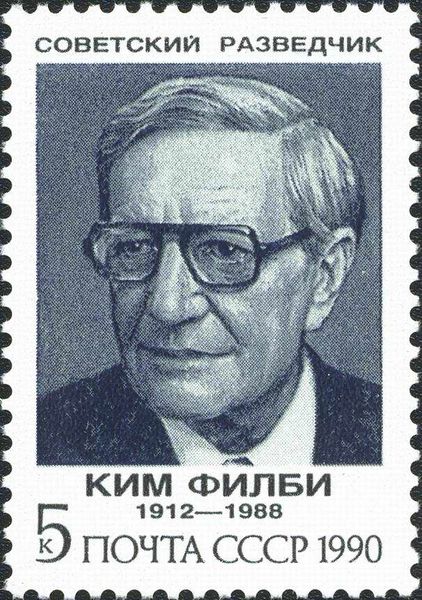

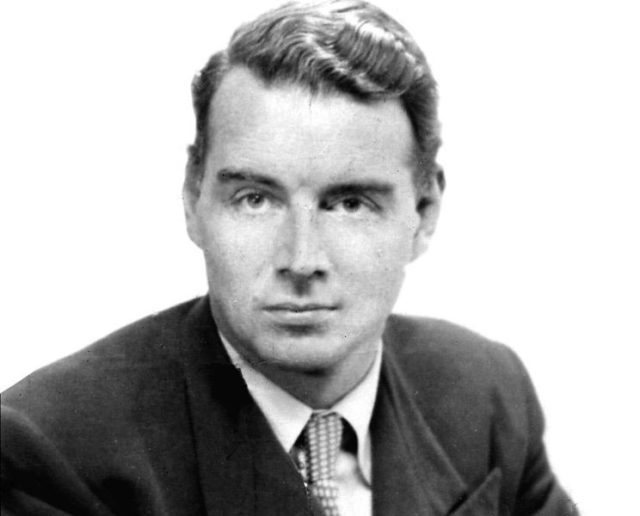

4. The Cambridge Five

When Soviet intelligence officer Arnold Deutsch met with Cambridge University graduate Harold “Kim” Philby in 1934, he came right to the point: “We need people who could penetrate into the bourgeois institutions. Penetrate them for us!” Philby eagerly agreed, beginning a lifelong affiliation with Moscow.

The freshly-minted spy also identified other potential recruits, and in short order, Deutsch managed to sign up four more Cambridge men: Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, and John Cairncross. All were dedicated communists and demanded no financial compensation for their espionage services. In time, the Soviet strategy of recruiting young, disaffected members of the British elite would yield rich rewards.

The Cambridge Five quickly obtained key positions in the British government and intelligence apparatus:

Harold Philby (ironically) headed the anti-Soviet section of MI6 (the British equivalent of the CIA).

Donald Maclean became Third Secretary at the Paris embassy in 1938, where he kept the Soviets informed about Anglo-German diplomacy. He then served in Washington from 1944 to 1948, achieving promotion to First Secretary. Here he became Moscow’s main source of information about US energy policy, greatly helping the Russians to evaluate the relative strength of their own nuclear arsenal.

Guy Burgess was recruited into the News Department of the Foreign Office in Britain, in the spring of 1944 by Alexander Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs, a position that gave him access to Foreign Office communications. Later Burgess became an assistant to Hector McNeil, Minister of State in the Foreign Office. As McNeil’s assistant, Burgess was able to transmit top secret Foreign Office documents to the KGB regularly, secreting them out at night to be photographed by his controller and returning them to McNeil’s desk in the morning.

Anthony Blunt was recruited to MI5, the Security Service in 1939. He passed the results of Ultra intelligence from decrypted Enigma intercepts of Wehrmacht radio traffic from the Russian front. He also admitted to passing details of German spy rings, operating in the Soviet Union.

John Cairncross worked in GC&CS, Bletchley Park on ULTRA ciphers during 1942 and 1943. In 1944 he joined MI6. During his time at Bletchley Park, Cairncross passed documents through secret channels to the Soviet Union.

Upon discovering that the authorities were closing in, Philby, tipped off Maclean and Burgess, prompting them to defect to Moscow in 1951. Philby joined them there in 1963, whereas Cairncross ended up in Italy and France. Blunt, whose status was revealed publicly by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher confessed in exchange for immunity from prosecution and was allowed to stay in Britain. None of the five ever faced espionage charges.

5. Aldrich Ames

Born in 1941 Aldrich Hazen Ames is an American CIA analyst, turned KGB mole, who was convicted of espionage against his country in 1994. He is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole in the high-security Allenwood U.S. Penitentiary.

Despite an obvious drinking problem and poor performance reviews, he advanced to become head of the counterintelligence branch of the CIA’s Soviet division. In 1985, however, while going through a financially disastrous divorce, Ames walked into the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., and offered to trade secrets for money.

As a CIA case officer, who spoke Russian and specialized in the Russian intelligence services, including the KGB, the USSR’s foreign intelligence service he was sent on overseas assignment in Ankara, Turkey, where he targeted Russian intelligence officers for recruitment. Later, he worked in New York City and Mexico City. In 1985, while assigned to the CIA’s Soviet/ East European Division at CIA Headquarters, he secretly volunteered to KGB officers at the USSR Embassy, Washington, D.C. Shortly thereafter, the KGB paid him $50,000.

During the summer of 1985, Ames met several times with a Russian diplomat to whom he passed classified information about CIA and FBI human sources, as well as technical operations targeting the Soviet Union.

Paid some $2.7 million over the next nine years, he moreover disclosed the identities of virtually every secret agent working for the Americans within the Soviet Union, at least 10 of whom were subsequently executed. Though U.S. officials had suspected the existence of a mole for quite some time, Ames avoided arrest until 1994, when the FBI finally closed in after uncovering incriminating evidence in his trash and on his computer.

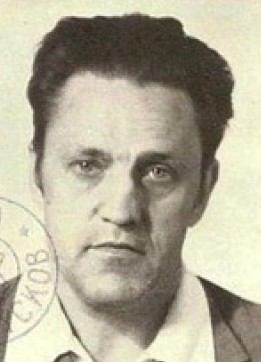

6. Adolf Tolkachev

Not every traitorous Cold War spy supported the communist cause. In early 1977, for instance, Soviet electronics engineer Adolf Tolkachev began dropping notes into the cars of U.S. diplomats, asking to meet with an American official. The CIA originally ignored him, worried that it would fall into a KGB trap. But Tolkachev, who worked at a military aviation institute in Moscow, persisted and eventually gained the CIA’s trust. From 1979 to 1985, he regularly stuffed classified documents into his coat in order to photograph them at home with a CIA-supplied camera.

For almost a decade after finally made contact he proved to be a tremendous reporting asset. He provided plans, specifications and test results on existing and planned Soviet aircraft and missiles. The information provided by Tolkachev saved the U.S. government billions of dollars in defense expenditures, a coup that prompted some intelligence historians to call him “the greatest spy since Penkovsky.” For this spy work, the CIA paid Tolkachev more than $1 million—the majority of which was held in escrow pending his planned defection—and supplied Led Zeppelin, The Beatles and other Western rock albums for his son.

Tolkachev claimed his distrust of the Soviet government arose from the persecution his wife’s parents had suffered under Joseph Stalin. He told the CIA he was inspired by Aleksandar Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov.

The collaboration came to an abrupt end in 1985, when it’s believed that former CIA agent Edward Lee Howard, and possibly Aldrich Ames as well, told the Soviets about Tolkachev’s activities. He was executed the following year.