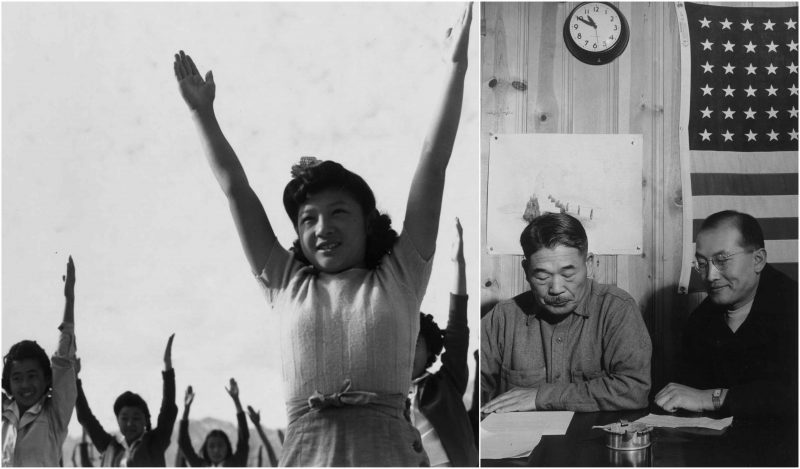

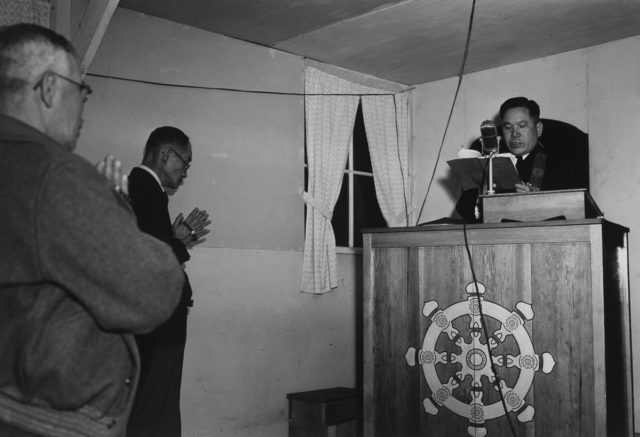

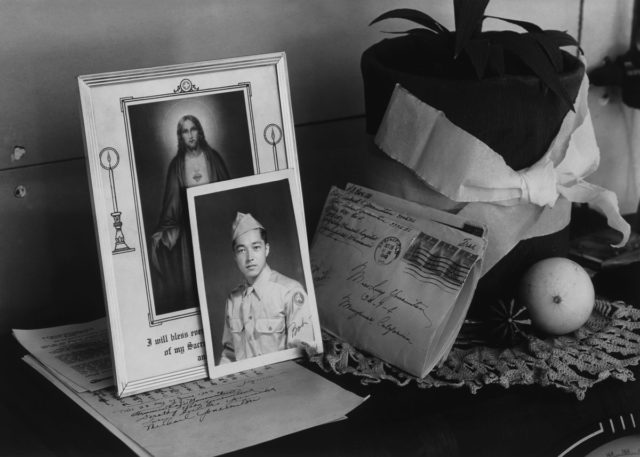

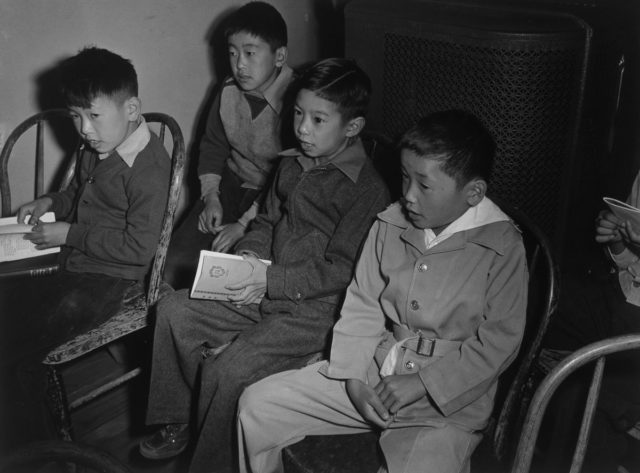

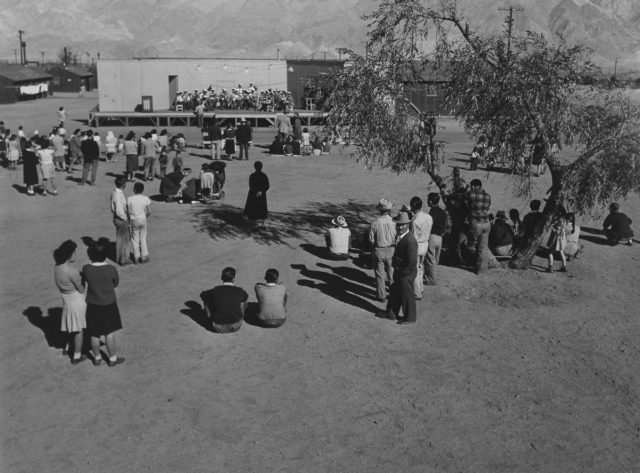

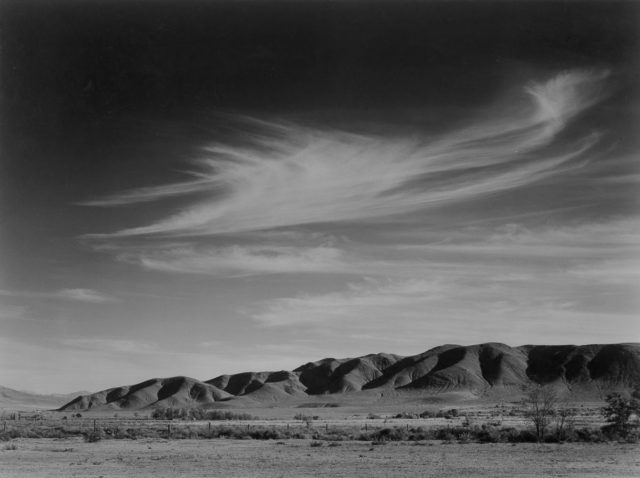

Manzanar is most widely known as the site of one of ten camps where over 110,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. Located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada inCalifornia’s Owens Valley between the towns of Lone Pine to the south and Independence to the north, it is approximately 230 miles (370 km) northeast of Los Angeles. Manzanar (which means “apple orchard” in Spanish) was identified by the United States National Park Service as the best-preserved of the former camp sites, and is now the Manzanar National Historic Site, which preserves and interprets the legacy of Japanese American incarceration in the United States.

Long before the first incarcerees arrived in March 1942, Manzanar was home to Native Americans, who mostly lived in villages near several creeks in the area. Ranchers and miners formally established the town of Manzanar in 1910 but abandoned the town by 1929 after the City of Los Angeles purchased the water rights to virtually the entire area.As different as these groups were, their histories displayed a common thread of forced relocation.

Since the last incarcerees left in 1945, former incarcerees and others have worked to protect Manzanar and to establish it as a National Historic Site to ensure that the history of the site, along with the stories of those who were unjustly incarcerated there, are remembered by current and future generations. The primary focus is the Japanese American incarceration era,[as specified in the legislation that created the Manzanar National Historic Site. The site also interprets the former town of Manzanar, the ranch days, the settlement by the Owens Valley Paiute, and the role that water played in shaping the history of the Owens Valley.

All photos Library of Congress