Prohibition marked one of the last stages of the Progressive Era. During the 19th century, alcoholism, drug abuse, gambling addiction, and a variety of other social ills and abuses led to the activism to try to cure the perceived problems in society. Among other things, this led many communities in the late 19th and early 20th century to introduce alcohol prohibition, with the subsequent enforcement in law becoming a hotly debated issue. Prohibition supporters, called drys, presented it as a victory for public morals and health. Anti-prohibitionists, known as wets, criticized the alcohol ban as an intrusion of mainly rural Protestant ideals on a central aspect of urban, immigrant, and Catholic life.

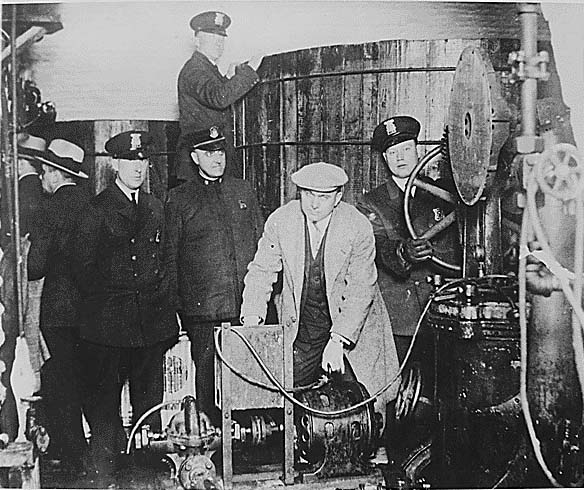

On October 28, 1919, Congress passed the Volstead Act, the popular name for the National Prohibition Act, over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto. The act established the legal definition of intoxicating liquors as well as penalties for producing them. Although the Volstead Act prohibited the sale of alcohol, the federal government lacked resources to enforce it. By 1925, in New York City alone, there were anywhere from 30,000 to 100,000 speakeasy clubs.

Although popular opinion believes that Prohibition failed, it succeeded in cutting overall alcohol consumption in half during the 1920s, and consumption remained below pre-Prohibition levels until the 1940s, suggesting that Prohibition did socialize a significant proportion of the population in temperate habits, at least temporarily. Some researchers contend that its political failure is attributable more to a changing historical context than to characteristics of the law itself. Criticism remains that Prohibition led to unintended consequences such as the growth of urban crime organizations and a century of Prohibition-influenced legislation. As an experiment it lost supporters every year, and lost tax revenue that governments needed when the Great Depression began in 1929

While Prohibition was successful in reducing the amount of liquor consumed, it stimulated the proliferation of rampant underground, organized and widespread criminal activity. Many were astonished and disenchanted with the rise of spectacular gangland crimes (such as Chicago’s Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929), when prohibition was supposed to reduce crime. Prohibition lost its advocates one by one, while the wet opposition spoke of personal liberty, new tax revenues from legal beer and liquor, and the scourge of organized crime